An historic district doesn’t just happen.

The reason the stately homes in Winnetka Heights are still standing is the blood, sweat and tears of these and many other urban pioneers.

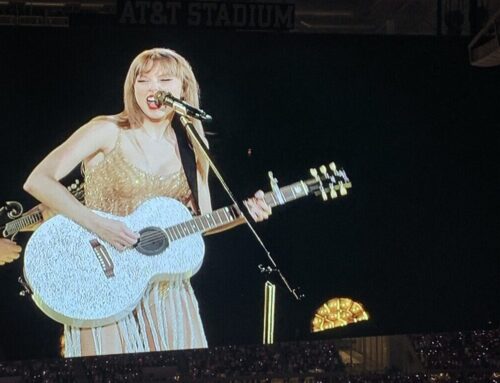

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9EXKtwisrBU[/youtube]Story by Ali Lamb and Ashley Hudson

In summer 1974, a 28-year old Mary Griffith mailed a letter to Alan Mason of the City of Dallas’ Department of Urban Planning. The core message was simple:

“I understand that you and a group of consultants are currently conducting a historic landmark survey program, which hopefully will result in a number of ‘landmarks’ being preserved under the provisions of the Historic Landmark Ordinance of the City of Dallas.

“It is with this in mind that I respectfully request your very serious consideration of the area in Oak Cliff known as the Winnetka Heights Addition for historic landmark preservation.”

To many, the neighborhood seemed headed toward dilapidation. Griffith, however, believed it might be saved. For Winnetka Heights history was rich, and although its buildings were in poor condition, its foundation was strong. In 1908, four prominent Dallas businessmen — Leslie Stemmons, R.S. Waldron, J.P. Blake and Thomas Scott Miller Jr. — platted the 50-plus square block area. Three years later, an advertisement ran in the Dallas Morning News describing Winnetka Heights as “Dallas’ Ideal Suburb.” Among other selling points were the absence of saloons and “cool breezes, fresh from the country; uncontaminated by smoke and dust of the city.”

It must have worked, too, because in the wave of construction that followed, wealthy Dallasites built sprawling Prairie-style homes in the burgeoning development with “every convenience obtainable.”

But during World War II, the lavish homes, born in optimism, began decaying in neglect. Husbands went off to war, and wives took on boarders as a means of income, dividing impressive homes into apartments or multi-family residences. By the late ’60s, roughly 80 percent of the neighborhood’s homes had been carved up. The historical integrity was melting away from Winnetka Heights, one absentee landlord and deteriorating home at a time.

Then the urban pioneers showed up, Griffith among them. Perhaps she did not realize that her letter to Mason had dislodged a formidable snowball, sending it down a steep mountain of ordinances and laws. Friends of the feisty woman might believe it more plausible, however, that she knowingly fired the first shot in a citywide snowball war.

After all, they know the whole story. They were there. Mary Griffith, an Oak Cliff native, had lived in her Winnetka Heights home with her husband, Charlie, for less than a year when Swiss Avenue in Old East Dallas received historic designation, prompting her to begin the preservation process in her own neighborhood. Griffith went on to co-found the Old Oak Cliff Conservation League, which secured the planned development zoning, or PD, that prevented historic homes from being further divided. She also sat on the first Winnetka Heights Neighborhood Association board during the successful petition for historic district designation. Her home was built in 1912 and is approaching its 100th birthday.

Griffith: We were aware of what was happening on Swiss Avenue. We thought, “What if we did something like that here? What if we got people interested here?” My husband and I, we realized it was a special neighborhood.

Mary Griffith’s two-story, white-framed home on 419 N. Windomere will celebrate its 100th birthday in 2012.

Carla Boss and her husband, Butch, live down the street from the Griffiths in a two-story white home built in 1914. The home had been vacant for eight years and was under a demolition order when the Bosses purchased it more than 60 years later. At that time, the PD had already frozen the residential density in Winnetka Heights — single-family homes had to remain single-family homes — and the Old Oak Cliff Conservation League was a highly active neighborhood organization. The league stepped in to help the young couple keep their home, and the Bosses have spent the last 35 years returning the favor.

Boss: We didn’t know what a PD was. We had no idea that this was a PD district. We just fell in love with the house. It was my dream to have a big old house to renovate. My dream, his nightmare.

Diane Sherman’s husband, Daniel “Corky” Sherman, grew up in Oak Cliff as Griffith had. Although his parents eventually moved to the Lake Highlands area, he always knew he would return. In the early 1970s, his conviction was strong enough to inform his wife that she had a choice: She could take him with Oak Cliff or not take him at all. Diane Sherman appeased her husband. They bought a home built in 1913, and she discovered an unexpected passion for her new neighborhood.

Sherman: We saw this announcement in the paper. It was a seminar being sponsored by the OOCCL. It was to attract people like us, urban pioneers. It was called “New Adventures in Oak Cliff: How to Renovate an Old House.” They led you through the process of what to expect, and we’ve been hooked ever since. It’s just like, “We’ve finally arrived. We’ve stumbled on our future.”

“My mother cried when she saw my house.”

In her letter to Mason, Griffith had specified a house that she believed embodied the neighborhood’s crisis, saying:

“Unfortunately, one of the more significant and stately homes in the area appears doomed to demolition (503 N. Windomere, built around 1912). This property, recently zoned ‘office,’ is a particularly good example of a more subtle but potentially more damaging deterioration that results when owner apathy and neglect combine with zoning incompatible with residential use.”

Griffith also had used 503 N. Windomere as the poster-house for deterioration on a flier advertising the OOCCL’s second meeting, with the headline: “Do you want to stop deterioration like this?” The meeting, held at St. Cecilia’s Church in August 1974, called for Winnetka Heights neighbors to assemble for the purpose of maintaining and improving the neighborhood.

What Griffith could not have known is that a young couple would soon buy the house on Windomere and restore it. To this day, Carla Boss loves to mention that her home was once Griffith’s epitome of deterioration. Though the flier is now a joke between friends, in 1974 it embodied a serious problem that, Griffith feared, would topple the neighborhood.

Griffith: At this time, when people bought, they were real urban pioneers. That term isn’t even used anymore. It wouldn’t be appropriate because most people want a home that’s fixed-up, and they almost like moving into a new house. They have all the latest things. There’s not a thing wrong with that. Some people don’t want to do that kind of work and — now that I think about it — why would they? We didn’t have to do a whole lot to our house. We were lucky.

Boss: We walked through the door, and you would have had to see it. There were holes in the walls. There was graffiti. The fixtures were gone. There was one bare bulb hanging from the center of the ceiling, but the beams, the box beams, the floors …

Sherman: My mother cried when she saw my house. At the time, there were 16 houses on my block, and only seven were owner-occupied. We felt certain that it would turn around. We were going to turn it around. My mother sat down on the front step and took a big drag off her cigarette, and she said — as tears are rolling down her face — she said, “I always hoped you’d have a nice, new house someday.” Just like that. And I said, “You don’t understand. I can’t live in Richardson. I can’t live in Fox & Jacobs. I can’t live, you know, in a cookie-cutter place. I have to live somewhere like this.”

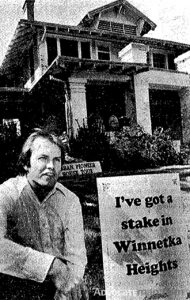

Urban pioneer Diane Sherman says her mother cried from disappointment when she first saw Sherman’s home at 107 N. Clinton: “I always hoped you’d have a nice, new house someday.”

“I guess they just weren’t thinking in terms of this type of neighborhood …”

Around this time, Griffith had sent the fateful request for historic designation to the Department of Urban Planning and had already knocked on many doors in Winnetka Heights, gathering supporters and launching the OOCCL. Mason’s response had been kind, but he was clearly hesitant to suggest the pursuit of a historic designation.

Griffith: The plan department looked at us, and I guess they just weren’t thinking in terms of this type of neighborhood being a historic district. All they had was Swiss Avenue to go to, and it’s quite spectacular. They suggested we do this planned development zoning.

Sherman: The PD froze the status of the district so that if you had an older home, you couldn’t divide it anymore. If you had a subdivided house, you could take it down from a quadruplex to a triplex to a duplex or all the way back down to single family. You just couldn’t subdivide it further.

Griffith: We were just trying to get them to do something to help us keep the neighborhood intact. They had never used a PD on an old neighborhood before. They decided to use it on us. In those days, in a neighborhood like this, banks didn’t like loaning because, if you were living in your single-family house, but next door to you was zoned for apartments, there’s no predictability that’ll stay that way. The owner might turn that into slum property, which often happened with those broken-up houses. Banks want predictability. The zoning built in some predictability. But the zoning took signatures. That was quite an undertaking.

“We were there to help stabilize things.”

This Oct. 10, 1977 photo of Butch Boss portrays his stance as an urban pioneer. Dallas Morning News Historical Archives

Roughly 600 structures fill the 164-acre neighborhood. The OOCCL had to convince a majority of the property owners to agree to new zoning that would freeze — and ultimately lower — the density in Winnetka Heights. In 1975 the neighborhood became the first in the city to be rezoned. Previously, PDs had been used only on new developments.

Griffith: Of course, explaining this to people wasn’t always easy because they tended to think, “Well, I’m going to get a lot of money for this property sometime. My house is going for townhouses.” That never happened; thank goodness. We had people out working their streets a lot like we did for the historic zoning later on.

Sherman: It was an interesting mix back then. You had some original residents still left, so you had some people in their 80s that welcomed people like us with open arms and were so glad we were there to help stabilize things.

Griffith: Things continued to perk along. We were on some house tours. We treated ourselves kind of like we were a historic district, even though we didn’t technically have that zoning. But then, of course, Munger Place in Old East Dallas got the designation in there somewhere. The plan department had started looking at their neighborhoods in the city. I guess they thought, “If we’re going to hold everything up to Swiss Avenue, that’ll be the only historic district.”

“There was a different mood by that time.”

Five years after Winnetka Heights was granted the PD, neighbors saw a shift in the city’s assessment of what constituted a historic designation. Change had also taken place in Oak Cliff. Preservationists from other neighborhoods joined the OOCCL, allowing the founding Winnetka Heights members to branch off and create the Winnetka Heights Neighborhood Association. These neighbors had a new name and an old dream. It finally came true in 1981.

Griffith: We just barely got that PD approved. Barely. But, by the time we got to having a historic zoning, the council members were loving us. I mean, that was a unanimous decision. They couldn’t wait to give us historic zoning, but that didn’t mean we didn’t have to work hard to show that we wanted it. We still did. I don’t want to take away from that, but there was a different mood by that time.

Sherman: And we were cautioned by the state. We were told by the state historic representatives that it was a very, big ambitious task to take on an area this large. They also told us that designation alone was not going to be an overnight fantasy. It wasn’t going to fix all of our problems. It was going to take decades, and we were going to have to maintain constant vigilance, constant monitoring.

Boss: I walked up and down sidewalks visiting with people, explaining the process and getting their signatures on petitions. I would say it would have to be 40-50 neighbors that were really involved in the trenches, so to speak, and then there were several that were responsible for submitting all of the data and documentation and everything. It was a big, big job.

Sherman: That was back when we didn’t have email. We had phones tethered to the wall. Not everybody had a computer, and if you had one, most people didn’t know how to work [it]. So it was crude.

“Sharing life”

Winnetka Heights reigned as the city’s largest historic district until Junius Heights in Old East Dallas, with more than 800 residences, joined the ranks in 2005. A few years later, one of Winnekta Heights’ key preservationists, Ruth Chenoweth, who passed away in 2006, created a brochure to tell the neighborhood’s story.

Chenoweth co-founded the OOCCL with Griffith, and many years later, when Griffith voluntarily fazed herself out of most neighborhood leadership roles, Chenoweth remained a formidable neighborhood activist. The Historic Preservation League, now Preservation Dallas, awarded her the Lantern Service Award and the Dorothy Savage Award for outstanding achievement in historic preservation. Because she could not contribute her crucial voice to this story, it seems fitting that it ends with an excerpt from her own version:

“Many original front porch swings attest to the close neighborhood ambiance that was generated through sharing life in this very special place.”

On the wide, wooden porch of Griffith’s 99-year-old home, a front porch swing still sways, echoing her dear friend’s words.