“The Approaching Herd,” 1902: Image courtesy of the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum

When Frank Reaugh began taking art students on sketching trips to West Texas and New Mexico around 1906, he accepted only the best of the best, and he expected a lot from them.

Each student was required to produce four sketches a day out in the West Texas wind and heat for about four weeks at a stretch. This was not glamour camping. Early on, they traveled by horse and mule. Later, Reaugh and five or six students and a female chaperone drove in Reaugh’s converted Ford touring car, acquired around 1920, which he nicknamed “The Cicada.” They slept under canvas tents, bathed in streams and cooked what they’d brought over open fires.

Reaugh, who is known as “the dean of Texas painters” and “the Cezanne of American impressionism,” lived in Oak Cliff, just off of Lake Cliff Park, at Fifth and Crawford.

Oak Cliff resident Bob Reitz has spent about 22 years researching Reaugh and following in the steps of those legendary summer sketching trips, which ended around 1940.

[quote align=”right” color=”000000”]Reaugh, who is known as “the dean of Texas painters” and “the Cezanne of American impressionism,” lived in Oak Cliff, just off of Lake Cliff Park, at Fifth and Crawford.[/quote]Reaugh and his family traveled by covered wagon from Illinois to Texas in 1876. Later, he studied art in St. Louis and Paris, and he noticed that the Flemish and Dutch masters had painted livestock, including cows. Back home, Reaugh began painting Texas landscapes in the field and rode along on cattle drives before there were fences in West Texas.

“He knew he was recording parts of Texas that someday wouldn’t be there,” Reitz says.

He could capture the majesty of a bovine like no one before or since. His interpretations of the Texas sky and sunset are incredibly subtle and detailed.

Reitz became enamored of his work after seeing Reaugh’s paintings in the library at the University of Texas at Austin when he was a student there in the 1960s. It wasn’t until much later that he would learn Reaugh’s connection to his hometown.

Reitz recruited a buddy, Gardner Smith, to take camping trips out into the West Texas wilderness because he wanted to experience what Frank Reaugh had decades earlier.

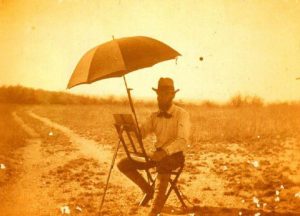

Frank Reaugh in the field: Photo courtesy of the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum

Reaugh also was a keen inventor. He practiced “en plein air” painting, where the artist paints out in nature on an easel. He found that his round pastels often rolled around too much, so he crafted a new pastel crayon in an octagonal shape. Reaugh also customized his own pastel colors, purples in particular, that would evoke the hues of Texas landscapes. Since he painted 3-inch-by-5-inch sketches in the field, he customized an easel for that size.

Those small paintings inspired Reitz and Smith, who served in the Vietnam War together. Neither of them are artists, but for decades, they traded haiku as a way to stay in touch. On their first Frank Reaugh camping trip in 1990, they started writing haiku in the style of the Japanese master Basho, inspired by their surroundings.

They felt this stripped-down form of poetry was the perfect way to honor Reaugh, who could convey so much in those tiny paintings.

After several camping trips, they had so many poems that they decided to compile them into a book. They produced the book themselves as Sun and Shadow Press, with string binding they did by hand. In all, they painstakingly produced seven volumes of haiku as well as the memoirs of Reaugh’s favorite student, Lucretia Donnell Coke, and the oral history of Reaugh’s life, which Oak Cliff native Coke had written out in longhand at Reaugh’s home in the 1940s.

[quote align=”right” color=”000000”]“He knew he was recording parts of Texas that someday wouldn’t be there.”[/quote]Several of those books are part of the Dallas Public Library’s Frank Reaugh collection, a permanent exhibit on the Downtown library’s seventh floor. Even though Reaugh lived in Oak Cliff most of his life and was the father of the Dallas Nine artistic movement of the 1930s, Dallas never has been any big champion of Reaugh. Most of Reaugh’s work — about 800 paintings — is in the Texas Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum near Amarillo. When he was alive, Reaugh had wanted Dallas to build a museum for his paintings. Instead, Austin got them. In 1937, eight years before he died, Reaugh gave about 200 paintings to the University of Texas at Austin. The Harry Ransom Center at UT will show all of them in “Frank Reaugh: Landscapes of Texas and the American West” Aug. 4-Nov. 29.

Part of Reitz’s mission, when he started following Reaugh’s West Texas and New Mexico paths in the `90s, was to get a permanent exhibit of Reaugh’s work in Dallas, and now there is one at the library. He also wanted to see someone write a book about Frank Reaugh from an art history perspective. Michael Grauer of the Panhandle museum is expected to publish one this year. And that’s not all. Filmmaker Marla Fields is working on a documentary about Reaugh.

After seeing for himself the places Reaugh painted, watching the sunrises Reaugh watched, Reitz says he is all the more intrigued by the artist.

“He makes me proud to be a Texan,” he says.