At Vivero Boxing Gym, fighting changes lives

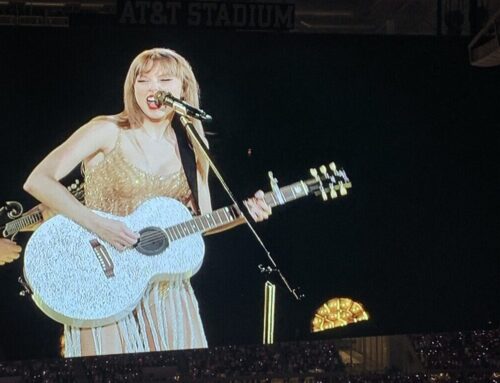

A 6-year-old Vergil Ortiz Jr. watches a sparring match from between the ropes at Vivero Boxing Gym.(Photo by Candice Chase)

British journalist Pierce Egan dubbed boxing “the sweet science of bruising” in the early 1800s. It’s a brutal sport that requires the strategy of a chess master, the strength of a dancer and the quickness of a sprinter.

Success in the sport, for a very few, could mean millions of dollars and worldwide celebrity. Or it could mean a few concussions, a respectable win-loss record and a following of dedicated local fans. Chasing the dream takes extreme discipline and toughness, but the ones in the chase say the pain is worth it.

A black-and-white photo shows then-6-year-old Vergil Ortiz Jr. leaning against the ring and intensely watching a sparring match. The title of the photo is “Ropes Scholar.”

Ortiz, now a Grand Prairie High School senior, started boxing at age 5, training six days a week at Vivero Boxing Gym.

Birthdays, Christmas, holidays, it doesn’t matter. Ortiz is in the gym two or three hours a day. Now 17, that’s been his routine for 12 years.

After clocking out from his warehouse job, Ortiz’s dad picks him up with a beep of the horn and makes the drive to Oak Cliff. He does it every day because he thinks Vivero gym is the best for his son.

“It matters who your kid’s coach is,” the elder Ortiz says. “You could have the fastest racecar in the world, but if you don’t have the best pit crew, and you don’t have the best driver, it doesn’t matter.”

Ortiz’s dad has put valuables in hock, frequently gone without lunch and made many other sacrifices for his son’s boxing career. He’s declined promotions at work in order to ensure predictable hours that allow the gym schedule.

The son runs cross-country on the varsity team since distance running is part of a boxer’s training anyway, but otherwise he sits out of extra curricular activities.

They don’t go to church on Sundays; they go to the gym.

Boxing is their priority.

Vergil Ortiz Sr.’s eldest son was born when he was 17. He had to start working fulltime, and his mother helped all she could, often working two jobs, to raise young Vergil.

The boxer, who won the national silver gloves three times and a gold medal in the Junior Olympics, fought his last amateur bouts at the Dallas Golden Gloves recently.

He is expected to go pro, and he has big-name suitors, including Oscar de la Hoya’s Golden Boy Promotions and former boxing champion brothers Joel and Jose Antonio Díaz, now highly regarded trainers.

When the Ortizes travel to out-of-state tournaments, they find a following in boxing fans, former pros and trainers. One California-based trainer, Robert Garcia, outfitted Ortiz in top-of-the-line gear valued around $1,000.

Ortiz is a well-rounded boxer who can fight well at close range, and he can knock out his opponents quickly. Plus, he has that something special, a spark that trainers have been able to see since he was a kid.

Ortiz is a good student, ranked 47th out of more than 600 students in his senior class. He is nicknamed “Clark Kent” because of the glasses he wears to read during downtime at tournaments. If and when he does go pro, he also will go to college, he says.

His dad acknowledges that his son hasn’t had a normal childhood. But he’ll never be asking “what if,” he says.

“I know this took part of his childhood away. It did,” he says. “Nobody brings their kids here for fun, really. If you’re going to do it, you have to do it all the way.”

Having fun

When Hector Beltran Sr. entered the ring for his first professional fight in 2009, he did a flip over the ropes.

Trainer Gene Vivero wanted to kill him.

“He said, ‘You could’ve broken both your ankles!’ ” Beltran recalls.

Beltran, known as “Handsome Hector,” was such a heavy hitter that he quickly knocked out his opponent. His pro career ended a little more than a year later, with a 12-1 record and one draw.

Beltran grew up in the neighborhood and started working out at Vivero’s gym when he was 12.

“I was walking home from my friend’s house one day, and I just noticed it and I thought it looked cool,” he says.

Beltran is the class clown of the gym.

Vivero often had to tell him, “Stop goofing around, Hector.” And, “Stop flirting with the girls, Hector.”

Vivero offered Beltran and his brother, Ulises, a way to be involved in organized sports. Their family is supportive, but they never had much money.

At Vivero, there is a membership fee, but no one has to pay if they can’t afford it. No one who wants to train is turned away.

Vivero, a 67-year-old trainer and former boxer, started the gym 23 years ago because he just likes the sport. He bought the building on Balboa Drive, a former auto mechanic shop, and built a ring.

He is now retired, but for years he operated the gym six days a week after his job running a line crew for TXU.

The gym has never made him any money. The fees he receives often are just enough (and sometimes not quite enough) to keep the electricity on and pay property taxes.

When the Beltran brothers were kids, Vivero paid for their gloves and protective gear. It’s not unusual for Vivero or his brother, Dennis, to give athletes rides and help them buy equipment.

“I’m forever indebted to them and grateful,” Beltran says.

About two years ago, the gym received official nonprofit status.

The Beltran brothers both found the discipline to finish high school, go to college and find jobs in the professional world. For fun, they train young boxers at Vivero.

Now a second generation, Hector Beltran’s 8-year-old son, Hector Jr., is training at Vivero. He wants to be just like his dad.

Over the years, Vivero has trained a few pros, two Olympians and a world champion, Quincy Taylor. But he really does it for the kids. Boxing gives them discipline and self esteem. It teaches them that when life knocks you down, you’ve got to get back up, Vivero says.

“I get a kick out of doing this stuff,” he says. “Everything else is just gravy.”