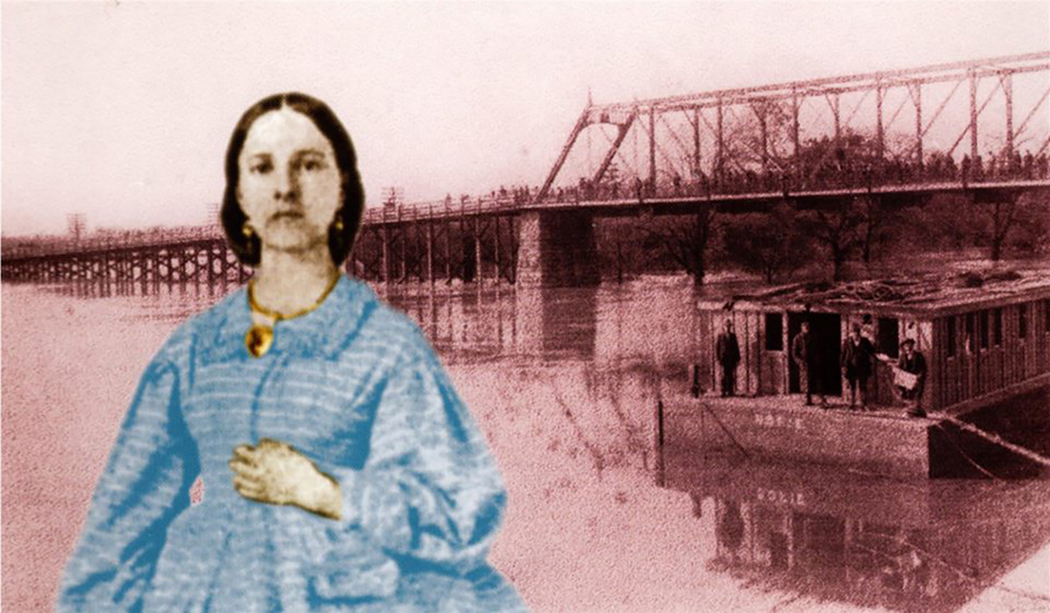

A photo montage of Sarah Cockrell and one of the old Commerce Street bridges. (Photos courtesy of “Sarah — The Bridge Builder: Dowager of a Dallas Dynasty” by Vivian Castleberry and the Dallas Public Library)

Sarah Cockrell was one of Dallas’ most important early capitalists

John Neely Bryan takes credit as the founder of Dallas.

Men such as Zachariah Ellis Coombes and William Henry Hord made history as the first white settlers of Oak Cliff.

Carl A. Mangold and Thomas L. Marsalis were the first to begin forming Oak Cliff into the residential neighborhood it is today.

But it was a woman, Sarah Horton Cockrell, who is considered Dallas’ first capitalist.

Following the American Civil War, Cockrell became an industry magnate, real-estate maven and transportation pioneer.

Cockrell was born in Virginia in 1819. The Cockrell family moved to a homestead near Mountain Creek Lake when Sarah was 25. In an 1845 letter to her sister, she recounted seeing her neighbor, Alexander Cockrell, at a dance on Thanksgiving night. Cockrell was a veteran of the Mexican War and one year her junior.

“I must tell you he looked like a dream come true — tall very handsome, that black hair perfectly groomed and the piercing blue eyes literally drilling into me. I had to pinch myself to remind me that he was a scoundrel, given to taking the Lord’s name in vain, a wild man not fitting for pleasant society.”

She married the good-looking scoundrel anyway. Together they built a cedar-log cabin on a piece of land near what is now the Mountain Creek Generating Station. The home consisted of one large room with a loft and storage room. They whitewashed the exterior, and it became known as the White House Ranch.

Alexander Cockrell traveled often to trade cattle, leaving Sarah to run the homestead. Like most Dallas pioneers, the Cockrell family held slaves.

In 1853, Alexander Cockrell sold his cattle ranch and bought Bryan’s stake in Dallas for $7,000. They first moved into Bryan’s cabin and then they lived in a five-room cottage on the north side of Commerce Street. He operated a brick business as well as sawmill, lumberyard, gristmill and freighting businesses.

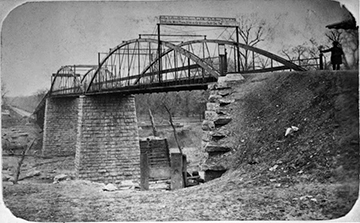

Cockrell had purchased Bryan’s ferry across the Trinity, at the time the only way between what is now Oak Cliff and Dallas. In 1854, he built a covered wooden toll bridge, having acquired hundreds of acres of land surrounding the Trinity River.

He owned many commercial and residential buildings, and he began building the three-story St. Nicholas Hotel in 1857.

This was still the Wild West, and on April 3, 1858, Alexander Cockrell was killed in a gunfight with a city marshal, Andrew M. Moore. Moore, who later was cleared of any crime, said he was attempting to arrest Cockrell for violating a city ordinance. But there was suspicion because Moore had been in debt to Cockrell.

Sarah had kept the books and managed correspondence for all of her husband’s enterprises; Alexander Cockrell, in fact, was said to have been illiterate. After her husband died, she became the woman in charge of all of the Cockrell holdings.

In 1859, the brick St. Nicholas Hotel opened on Commerce Street under her management.

The following year, Sarah appealed to the State of Texas for the right to build an iron toll bridge across the Trinity. She even appeared before the Texas Legislature, a highly unusual move for a woman at the time. The state granted her approval to build an iron bridge across the Trinity. The American Civil War delayed that project, but the first iron bride across the trinity was constructed in 1872 under the direction of the Dallas Iron and Bridge Co.

Sarah, being a woman in the Victorian Era, did not sit on the board of directors. Her interests were represented instead by her son and her son-in-law.

In the following years, she acquired a flourmill, entering what was then Dallas’ No. 1 industry.

She was a real-estate expert, having negotiated 53 land deals in 1889 alone, according to the Texas State Historical Society.

Besides all that, she raised five children — the oldest was 8 and the youngest 2 at the time of her husband’s death — and she held open houses, inviting the community into her home. She threw what is thought to have been the first formal ball in Dallas at the St. Nicholas Hotel, which burned down in the 1860 fire that destroyed much of the town.

Sarah Cockrell died in 1892, and she owned so much real estate that her will was 24 pages long.

She donated the land, at Ross and Harwood, for the First Methodist Church. And a stained-glass window there commemorates that contribution.

The Cockrell family left a long string of descendants, many of whom still live in Dallas. And their name remains prominent. Next time you’re driving on Cockrell Hill road, remember: It’s named for a pioneering woman.

In 2004, Vivian Castleberry published a book about Sarah Cockrell titled “Sarah — The Bridge Builder: Dowager of a Dallas Dynasty.” Castleberry received the Oak Cliff Lions Club’s Humanitarian Award in April.