Giovanni Valderas has a statement to make about gentrification, and he’s saying it in the most festive way he could find.

The 38-year-old Oak Cliff native is the assistant director of Kirk Hopper Fine Arts in Deep Ellum and has served as vice chair of Dallas’ Cultural Affairs Commission.

But some of his own work can be seen in the streets of Oak Cliff and West Dallas.

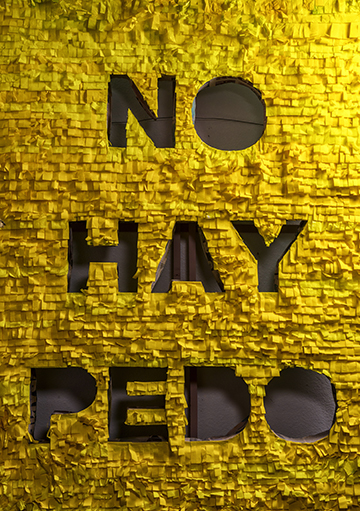

Valderas uses traditional piñata techniques to create signs, which you might’ve seen pop up on vacant lots and near new developments. These signs manage to blend in and catch the eye at the same time, and they convey Spanish slang. One asks, “Quien manda?” or “Who rules?” Another says “No hay pedo,” which means “No problem,” but also can be translated as “There’s no fart.”

The City of Houston commissioned one, a 40-foot by 60-foot banner for a downtown building, which reads “Ay te miro,” a slangy way to say “I’ll see you later” but translates literally to “I see you.”

Valderas says he uses humor and piñata designs because he doesn’t want to come across as hostile. But he thinks the message is imperative.

There are almost 35,000 registered voters in City Council District 1, north Oak Cliff. But only about 2,000 of them typically vote in local elections.

“It’s time to wake up and be engaged and involved with the world,” he says. “Who does run this town? Is it us, or is it them?”

Recent changes and developments in Oak Cliff inspired the artistic protest.

As a kid, Valderas used to hang out with a cousin who lived in the Colorado Place Apartments on Fort Worth Avenue at Colorado Boulevard. When they were torn down, he wondered where all of those families would go. Then the land sat empty for years.

Valderas uses relatable Spanish slang and humor in his pieces. “No hay pedo,” means “No problem” but also can be translated “There’s no fart.” (Photo by Danny Fulgencio)

That eviction and subsequent dormancy felt so unjust to him. Developers do whatever they want without regard to how it affects quality of life for the people who already live here, he says.

“The Latino community brings so much to Dallas as far as a sense of place, and it’s kind of being disrespected,” Valderas says.

Valderas thinks affordable housing is the No. 1 political issue facing Dallas. West Dallas is a microcosm of that, and unless serious action is taken, it’s not going to get better, he says.

Valderas first realized he wanted to become an artist as a teenager at the Ice House Cultural Center, which later evolved into the Oak Cliff Cultural Center. There, he worked on murals and met pal David Lizano, the founder of Cara Mía Theatre Co. Valderas later worked at the cultural center part-time, where he and Lizano helped put on a show of historical photographs depicting Oak Cliff architecture.

He went on to receive a master of fine arts degree from the University of North Texas in 2012, but he says he still identifies as a product of cultural centers.

When Mayor Mike Rawlings appointed Valderas to the Cultural Affairs Commission, he was eager to dig in. He served on the panel that created $5,000 service contracts for individual artists, and he says he’s grateful for the inside look at City Hall.

But what he saw was disheartening, Valderas says.

The city is willing to spend millions of dollars on the big and glamorous. It agreed last year to pay $15 million over 10 years to bail out the AT&T Performing Arts Center, for example. But there’s less support for individual artists and cultural centers. Consider that Dallas has 14 City Council districts but just four cultural centers. The new $5,000 individual artist contracts are better than nothing. But the City of Houston, for example, recently announced $370,000 in grants for 37 individual artists.

Valderas points to his friend Rachel Rushing’s Sunset Art Studios in Elmwood as an example of the type of grassroots work the Dallas art scene needs. The studio received grants totaling almost $14,000 from the Contemporary Art Dealers of Dallas and the Dallas Office of Cultural Affairs so that Rushing and partner Emily Riggert can offer free studio space to local artists. In turn, the artists are expected give something back to the community, such as offering open studio days or somehow incorporating neighborhood residents into their projects.

“[Rushing] walks the block and knocks on doors,” to encourage community involvement with the studio, Valderas says.

He intends to continue his piñata project, called “Forged Utopia,” having applied for a $2,000 grant from the Nasher Sculpture Center. If he wins it, he plans to design and produce political yard signs that look like his handmade piñata signs. A website with links to information on voting and other ways to become politically active would accompany the effort.

Valderas is one of several neighborhood artists who recently joined the Texas Organizing Project, an Oak Cliff-based nonprofit whose mission is to combat economic inequality in Texas.

The artists plan to work on bringing more community involvement to the arts and to advocate for cultural policies in the City of Dallas that benefit underserved neighborhoods and individual artists.

“Artists can really change things,” Valderas says. “Our work is visual, and we can put a different spin on things.”