Look past the news of the day and you’ll find a story worthy of the big screen. It’s an entertaining tragedy — unless you’re a taxpayer, parent or child in the district’s schools.

Only nine people control a $1.8 billion budget that impacts 157,000 schoolchildren — and the economic future of Dallas. Art by Christian Welch & Jynnette Neal Photo by Danny Fulgencio

Like any good movie, the Dallas ISD story begins with a simple premise: Once upon a time, trustees of all races work together to save the district’s children from an educational nightmare.

As in any good movie, though, there is plenty of conflict and drama along the way.

As the story proceeds, DISD hires a superintendent with great ideas for reform but seemingly no personal skills. Some trustees fund election campaigns to defeat fellow trustees. Two trustees bash a third trustee on an accidentally recorded phone call. A group of seemingly powerful Dallas politicians botches a coup designed to replace the board of trustees.

The “good guys” (self-described “reformers” in this story) haven’t always been good. The “bad guys” (in this story, those not sold on “reform”) have some good reasons for being bad.

And let’s not forget the ever-present issue of race and discrimination always lurking in the background of every scene.

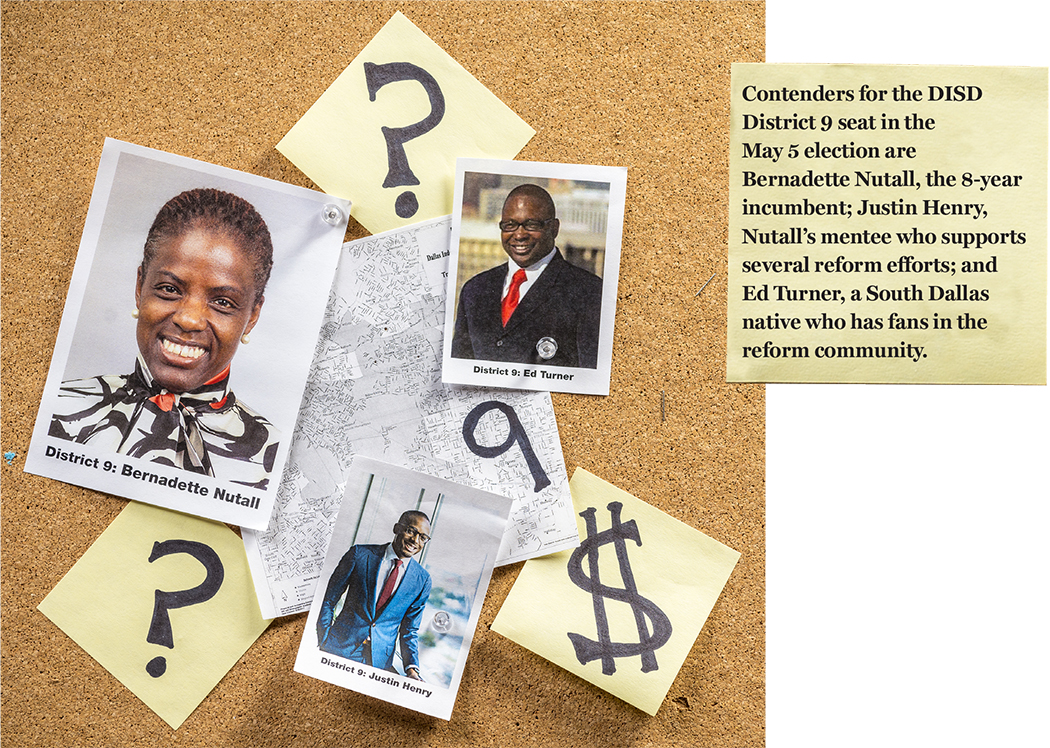

“We are the worst public enemy to black children in Dallas?” District 9 Dallas ISD trustee Bernadette Nutall asks rhetorically about a column written by a local journalist. “That was hurtful.

“African-American board members have always been willing to work across the table, but the problem is when we don’t do what you say [to] do, how you say [to] do it, we’re the problem,” Nutall says.

The African-American DISD trustees “are always the ones that have to do the olive branch,” she says, “and you want us to come and be like, ‘Yes, Massa, I need to think whatever you say [to] think.’ ”

So sit back, try to relax, and grab some popcorn and a bottle of Advil.

The cliffhanger: Will there be a happy ending?

Establishing shot: What is education reform?

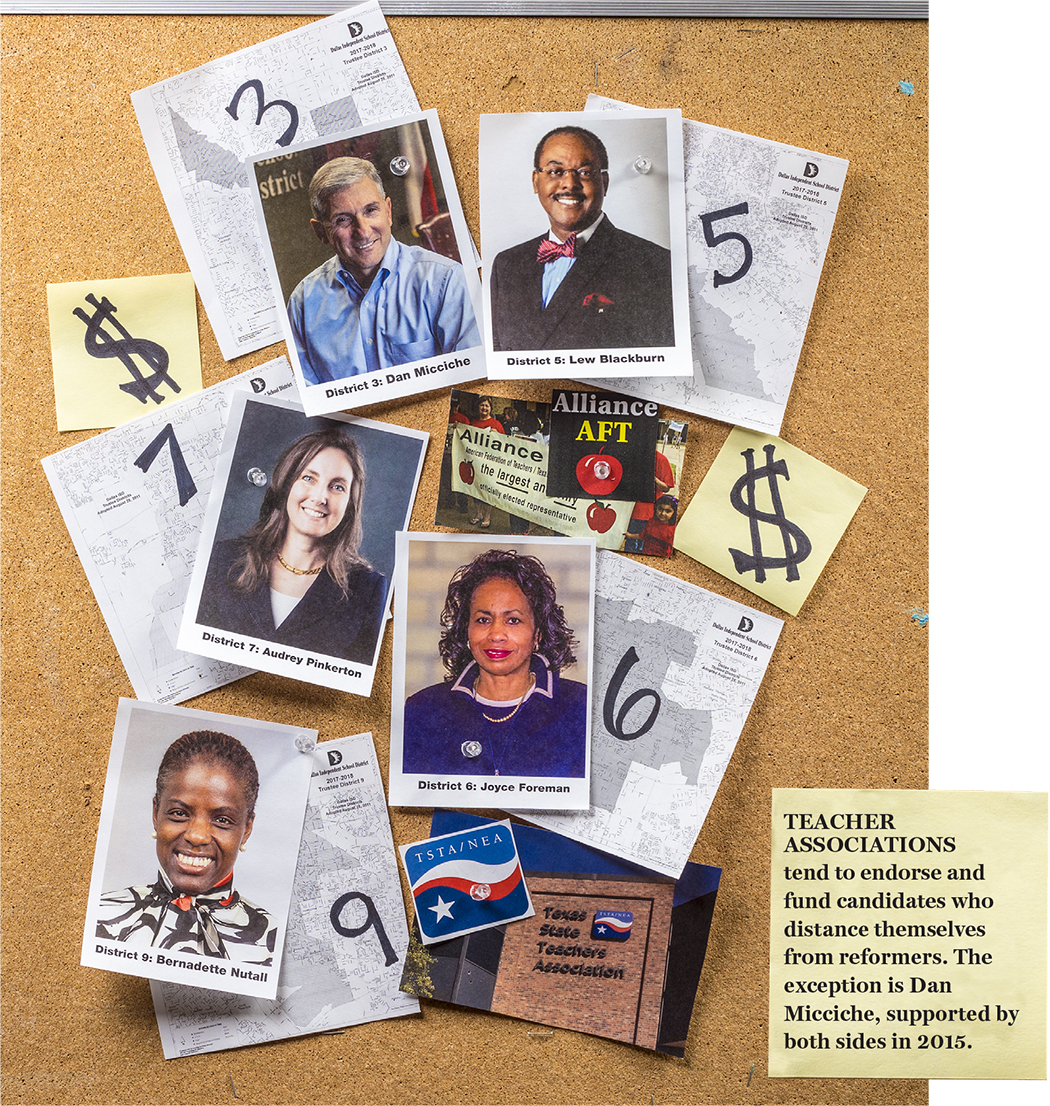

No one agrees on the definition, not even the people who identify as reformers, but here in Dallas, reformers champion data-driven academic policies, such as quality pre-K for everyone, and are willing to move quickly to change the status quo. One sharp political divide is over reformers’ successful push to use student test scores and frequent evaluations to identify and reward effective teachers. Other, more risk-averse trustees value experienced teachers and community support rather than top-down mandates and standardized test results.

Set the scene: A board divided

Two years ago, Audrey Pinkerton faced an opponent with three times the money in his war chest and the Dallas business community on his side. But she still handily won the race for the District 7 seat on the Dallas ISD board.

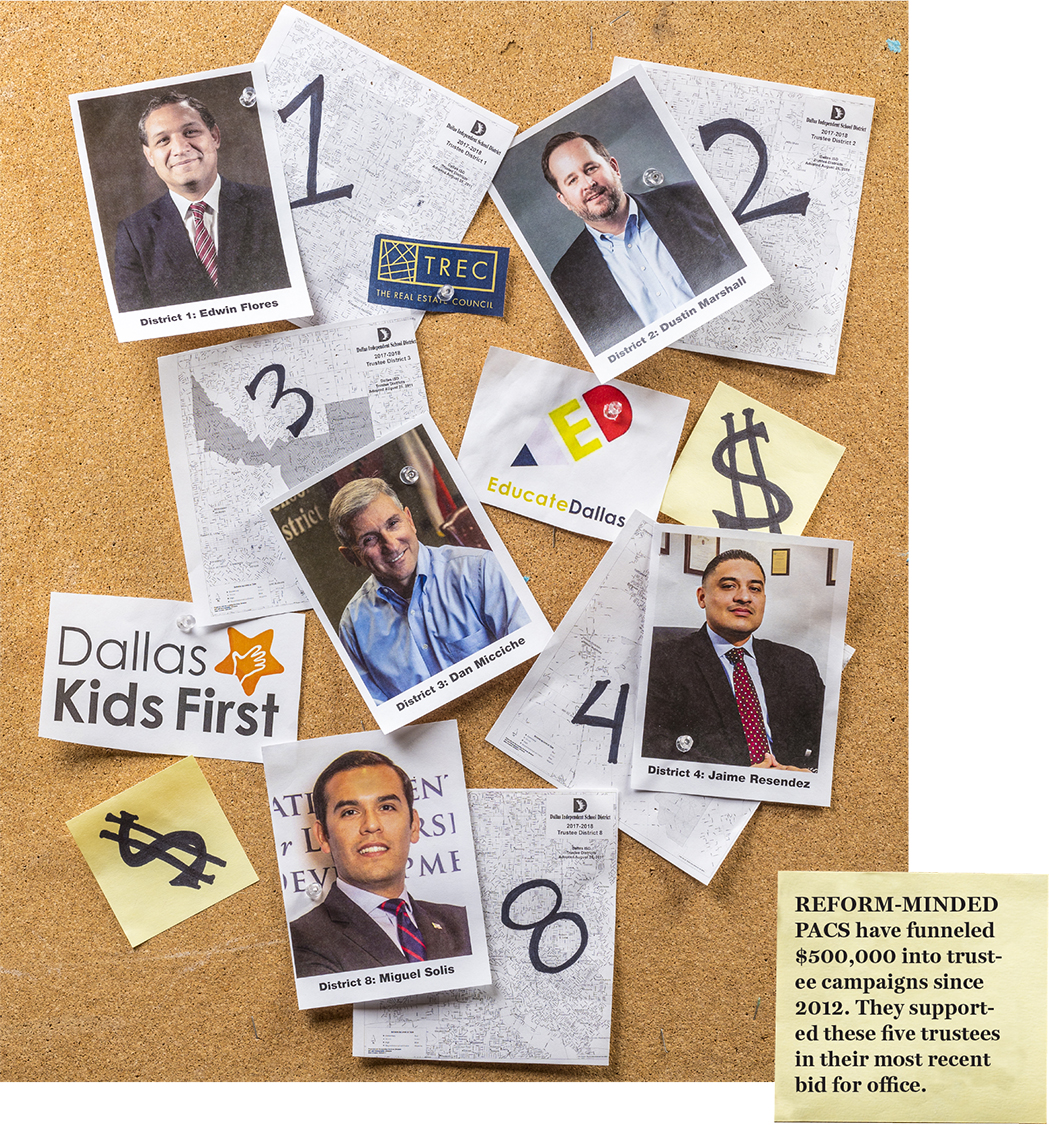

Her opponent, Isaac Faz, and her predecessor, Eric Cowan, saw themselves as education reformers. It’s a staunch identity for some and nebulous for others. But five of the nine trustees, a simple voting majority, are reformers who tend to aggressively push policies and funnel funds into programs that research has shown to be effective in educating children — especially those who live in poverty, as nearly 90 percent of DISD children do.

The other four trustees proceed with more caution. Even though the board votes unanimously almost 80 percent of the time, the minority cohort is more likely to question sweeping policy changes. Some center on fiscal responsibility or disagreements about best practices.

The price of admission

A single Dallas ISD board candidate raised $246,722 last year — the highest amount for a race in DISD history. Yet only 12 percent of registered voters headed to the polls. With 11,302 ballots cast for the winning candidate, that translates to $21.83 per vote.

By comparison, all three trustee candidates ran unopposed in 2011. After that, two education PACs formed, collectively spending nearly $500,000 on board races over the next five years.

But much of it comes down to trust. As hundreds of thousands of dollars pour into campaign coffers, PACs and nonprofits, all in the name of progress, it stirs the suspicions of those who see it as wealthy white men’s attempt to take over public education.

At a high level, I support education reform in the sense of working to make schools better, to better educate students, to better prepare them to meet the workforce demands of the next century. The devil’s in the details. What the parents are seeing is that many policies are not working well and not having the intended effect. They look at what’s going on in schools in terms of the loss of good teachers and good principals, and they begin to ask, why is this happening?

—District 7 Trustee Audrey Pinkerton, shortly after she was elected to represent Oak Cliff on the Dallas school board

Fade-in: Empowered without an election

“Without a single vote cast, one-third of the board was sworn in.”

That’s how Melissa Higginbotham describes the event that birthed Dallas Kids First, a political action committee that formed in 2011. That spring, the Dallas ISD board election was canceled because only three people filed to run for the three open seats.

Around the same time, the Dallas Chamber of Commerce was discussing how to attract big companies to the city. One of the reasons Dallas was being passed over for the suburbs was the reputation of its public schools. The chamber’s education PAC, Educate Dallas, emerged to deal with this problem by tackling school board races.

A few months prior, Mike Morath — who, within five years, would ascend to Texas’ highest education position — met businessman Todd Williams over lunch. An hour turned into four as the two conversed about their passion for public education.

They shared a lot in common. Both were products of public schools — Williams from DISD’s Bryan Adams High School in ’78 and Morath from Garland High School in ’95. Both had experienced business success — Williams as a Goldman Sachs partner and Morath as a software entrepreneur. Williams had retired, and Morath had sold his company for millions.

And both, with time and money on their hands, were considering running for the Dallas school board. They left lunch agreeing that Morath would run, and Williams would create an organization to connect the dots about what is and isn’t working in public schools.

Morath was one of the three unopposed DISD candidates that May, the same month that former Pizza Hut CEO Mike Rawlings was elected mayor of Dallas. Rawlings joined the chamber’s new strategy of focusing on public education and named Williams his education advisor. Out of that came the Commit! Partnership. For five years, this organization has used data and research to identify best practices that will support Dallas County students “from cradle to career.”

It was a “constellation of forces that ended up being at the right place at the right time,” one reformer recalls. At that point, the Dallas business community had disengaged from public schools because their children no longer attended them.

Flashback: White people have left the (public school) building

The percentage of white, black and Hispanic students attending Dallas ISD has changed drastically over the last five decades.

54% / 36% / 10%

in 1971, the year court-ordered desegregation began.

6%/ 31% / 61%

in 2003, the year court-ordered desegregation ended, after white families left DISD for private school or the suburbs.

5% / 22% / 70%

in 2018.

Williams regularly walks into rooms full of Dallas executives to give Commit presentations and asks how many people attended public school. Hands shoot up. When he asks how many send their children to public school, hands are sparse.

“My fear is in 20 years, my replacement goes into a room and nobody can raise their hand. God help our city,” Williams says. “I knew that I had to talk to them in a language that they spoke, and that was data.”

He joined the board of Uplift Education, the largest charter network in Texas, and made a generous donation that led Uplift to open a namesake school, Williams Prep, in 2007. After years on the board, he concluded that “we can grow Uplift 25 percent a year, and it will take us 25 years to have the impact Dallas ISD could make.”

“The solution is traditional public schools, and that’s how I spend my time,” he says. But to people who distrust him, he says, “I think they just look at me and see the surface. They see a rich white North Dallas guy who worked at Goldman Sachs.”

![“You want us to come and be like, ‘Yes, Massa, I need to think whatever you say [to] think.’ ” —Bernadette Nutall, DISD District 9 Trustee / “I think they just look at me and see the surface. They see a rich white North Dallas guy who worked at Goldman Sachs.” —Todd Williams, founder of the Commit! Partnership](https://lakewood.advocatemag.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/nutall_williams_1050.jpg)

Cut to: The voicemail incident

Dallas Kids First started endorsing candidates in 2012. Their biggest statement was supporting newcomer Dan Micciche in his challenge of incumbent Bruce Parrott for the Far East Dallas seat. Micciche raised more money than any other board candidate in history that spring with nearly $90,000, much of it coming from the two new education PACs.

The seemingly sleepy race was in southern Dallas, where incumbent Bernadette Nutall was defending her seat against then 20-year-old Damarcus Offord. Nutall, in her first term, had voted months before the election to close 11 Dallas ISD schools. The decision earned her praise from the Dallas Morning News editorial board, who noted that “Nutall, in particular, showed courage” because “five [schools] were in South Dallas, an area she represents.”

Both of Dallas’ new education PACs endorsed Nutall. Another Morning News editorial that January named her alongside Morath and Trustee Edwin Flores as “a bloc that appreciates the value of education reforms.”

Nutall traveled with Todd Williams to L.A., Indianapolis and Cincinnati to study nonprofits after which Commit would be modeled. When Dallas Kids First discovered that only three of every 100 black boys who started in Dallas ISD graduated high school college-ready, Nutall and Morath toured southern Dallas churches to preach the urgency of the problem.

[Extra feature: Are Dallas ISD graduates ready for college?]

Then came the “voicemail incident.” Two months after Nutall was re-elected in 2012, Morath failed to hang up after leaving her a voicemail. The ensuing, recorded conversation between him and former trustee Nancy Bingham “dealt with [Nutall] as a board member and questioned whether she reads board documents,” according to a Dallas Morning News story.

The two trustees discussed the situation, worked it out and were moving on, the story said. But that story was the last time Morath and Nutall were described as having “a good relationship.”

Zoom in: The vote to reject free money

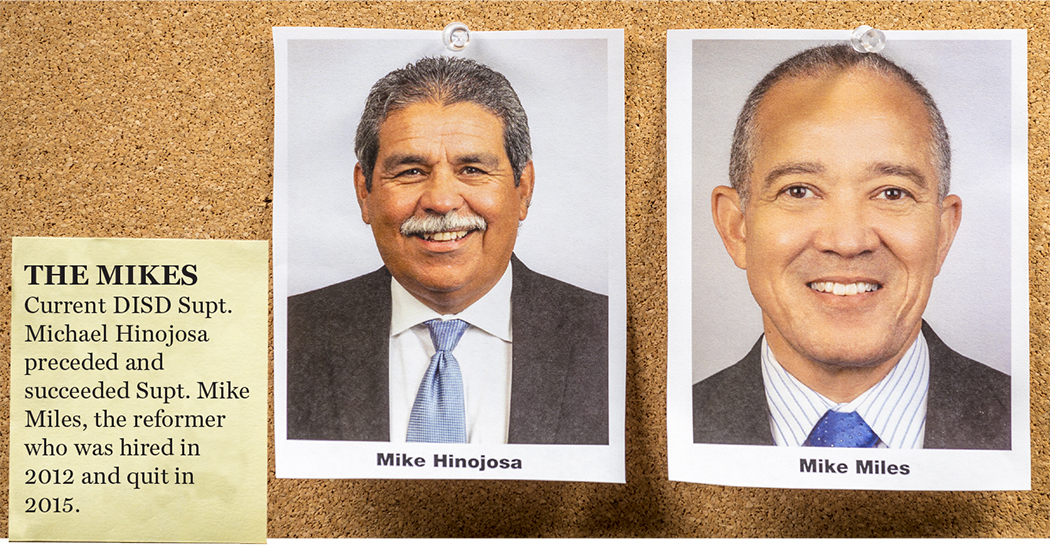

Superintendent Mike Miles came from Colorado in April 2012 with the reputation of being “a reformer, an innovator and someone not afraid to shake the status quo.” His vision was to pay teachers according to their performance, demand higher graduation rates and college entrance exam scores, and form a leadership academy to create a pool of principals to replace those who couldn’t cut it.

[Deleted scene: Was Teach for America the catalyst of education reform?]

Less than two months after she voted to hire him, Nutall told Miles she would vote against his plan. In an article headlining their “testy exchange,” Miles told Nutall she should “resign yourself to the fact that there’s a new superintendent … You asked me to put together a plan to move the district forward. I’ve done that.”

Miles gave the southern sector trustees a force to galvanize against. A year after Miles arrived, Observer columnist Jim Schutze accused Nutall and Trustee Lew Blackburn of being “at war with Superintendent Mike Miles over school reform.” Schutze had obtained letters and emails from DISD executives complaining about Nutall’s threats that if they removed certain southern Dallas principals, “the community will come after you.”

She later rejected a plan to infuse schools in southern Dallas with $20 million. More than half of the money would come from SMU and nonprofits to pay for things like more teachers and better preschool programs. Nutall was upset that the community wasn’t consulted.

“What this board is doing is dumping something on South Dallas. You continue to disrespect and be dismissive of the southern sector of Dallas,” Nutall said before the vote. “What I’m asking you to do is not to come into South Dallas and just experiment with our children.”

[Extra feature: Can pre-K fix Dallas’ problems?]

The plan passed, and other board members expressed surprise that Nutall opposed free money that would improve schools in her district. Micciche conceded that it was an experiment, but said “we’re experimenting by bringing extra resources to the table. We’re not experimenting by doing something bad to somebody. We’re trying to address the needs that have long gone unaddressed.”

Why would a trustee who “represents high schools that send thousands of young people straight to prison unable to read or write and without a prayer for decent life” decline such an offer, Schutze asked in a subsequent column. Now an opinion writer, Schutze spent decades reporting on Dallas and wrote a book, “The Accommodation,” which describes the handshake deals between Dallas’ black pastors and white business leaders as schools were desegregated.

“The elected leadership of southern Dallas is a remnant of the old ghetto over-class of segregation days,” Schutze wrote. “Because the civil rights movement never shook this town very hard, that leadership class, dominated by separatist clergy, still holds sway.”

Action: Board member is tossed out of school

Back in 2013, Schutze wrote, “The real enemies of these children are not white. They are black.” He reiterated this in a column last August following a vote in which Nutall, Blackburn and Trustee Joyce Foreman voted against a proposal that could have funneled up to $55 million into southern Dallas schools, mostly from taxes paid by northern Dallas residents.

Nutall, still reeling over Schutze’s accusations, agrees with him on at least one thing: “The civil rights movement never shook this town very hard.”

“Dallas never had a movement,” Nutall says. “Sometimes in movements, it creates cleansing. It creates people coming together. It creates the uncomfortable time to talk about the issues under the table, to understand, and then out of that can come great solutions.”

Because it never happened in Dallas, she says, “that history is still played out in the board table today. At the end of the day, all of what’s going on in history ends up to one word: control.”

The 2014 “home rule” effort epitomized the business community’s attempt to control Dallas, Nutall believes. She’s not alone in this belief. The proposal was Morath’s idea to circumvent what he saw as school board dysfunction. Instead of less than 10 percent of voters electing representatives, he envisioned a system where some trustees would be appointed and any could be ejected if students were failing. Home rule was backed by many of the same people involved in education reform PACs.

“There is a group of people who feel they know what’s best versus it being a collaborative effort,” Nutall says.

One of her opponents in the upcoming May election, Ed Turner, calls home rule the moment he was “baptized in politics.” A graduate of the “great James Madison High School,” Turner had returned to his neighborhood as a community organizer and worked against home rule.

“The way it came about was kind-of rushed, and people in our community do not appreciate anything that seems top-down. Things have to be grassroots,” Turner says.

Another of Nutall’s opponents this May, Justin Henry, was among the first reformers who block-walked for Micciche during the 2012 election. Henry considered Morath a friend. But the first time he heard about home rule was when he read the newspaper.

“The ripples it put out through our community, that one part of Dallas was trying to dictate what was best for us … The trustee of District 2 still does not talk to the trustee of District 9,” Henry says of Morath and Nutall. “And the only thing that separates them is the Santa Fe Trail.”

Home rule was the turning point in the reform effort. Even supporters who believed in the merits of what it could do for schoolchildren regard it as a disaster and a reversal of progress.

The effort also had political consequences for reformers. While signatures were being collected for the home-rule petition, reformers were trying to flip a seat in southern Dallas. But the $105,000 in campaign funds — which came mostly from northern Dallas zip codes, including $15,000 from Morath — couldn’t secure their candidate’s win.

[Behind the scenes: 11 big donors to education reform in Dallas]

Things got worse a few months later when, on Miles’ orders, security guards wrangled Nutall out of Billy Dade Middle School in her district. The superintendent was at the school for a staff meeting after a personnel shake-up. When Nutall showed up uninvited, he accused her of trespassing and interfering.

“You can’t throw an African-American woman out of an African-American school in South Dallas,” Henry says. “There’s nothing you’re going to get out of that that’s going to further our goals of getting opportunities for the schools, for the kids.”

Nutall doesn’t see her role on the board as a creator of policy. DISD has stacks of policies that aren’t followed or funded, she says, and she questions the point of adding to it. She believes her job is to advocate for schools in her district by ensuring that they have the resources policy calls for.

This is a common criticism of Nutall — that her heavy-handed tactics in schools overstep her bounds as a board member. In the Dade situation, however, even her critics believed Miles had gone too far.

In 2015, Nutall ran for re-election and again faced Offord. This time, reformers endorsed and financed Offord, hoping to unseat their friend-turned-foe.

It didn’t work.

Aerial shot: The trustee whose kids go to private school

“We are working against monolithic efforts to dismantle DISD under the guise of ‘reform,’ and those leading these efforts have power and money and are doing so for their personal gain. … Their work on a special interest agenda is hurting our children, particularly children who are the most vulnerable in our community.”

Thus read an email from Lori Kirkpatrick to her supporters on June 10, 2017, the day she faced Trustee Dustin Marshall in a runoff election. DISD District 2, which they were competing to represent, forms a doughnut around the Park Cities, looping through pockets of wealth in East Dallas, Preston Hollow, Oak Lawn and Uptown.

East Dallas is a neighborhood where many people with the means to give their children a private education still choose public schools. It might seem like fertile soil for a movement that espouses using funding and research to provide the best outcomes for students. But it is also a hotbed of progressives, question-askers and city-hall barnstormers who don’t like to fall in line with the powers-that-be.

[Deleted scene: What does ‘education reform’ mean to you?]

District 2 was Morath’s territory before Gov. Greg Abbott called him to Austin in late 2015 to serve as the Texas Education Agency Commissioner. Miles had thrown in the towel a few months earlier, and reformers’ hopes were dashed.

Desperate to hold onto Morath’s trustee seat, reformers mobilized behind Marshall and filled his coffers with $56,000 to finish the final year of Morath’s term.

If the strategy was to ward off contenders, it failed. Marshall ultimately raised five times as much as his fiercest competitor, Stonewall Jackson Elementary and Travis TAG parent Mita Havlick. She came up only 42 votes short in the runoff.

The close vote underscored voters’ suspicions of Marshall — why did his children attend private school at Greenhill, his alma mater, rather than Preston Hollow Elementary, the DISD school two blocks from his house? Why did he tout his experience on the board of Uplift Education, a charter school operator that draws from the same pool of tax money as DISD schools? And why were his campaign coffers allegedly full of “dark money” from real estate moguls, Park Cities zip codes and wealthy people who didn’t send their children to public schools?

Some wondered, what did this guy want with DISD?

Seven months later, Kirkpatrick attended a January DISD board meeting where trustees approved a resolution supporting more funds for public schools and opposing school vouchers or “any program that diverts public tax dollars to private entities.” The resolution also included a stance against Texas’ proposed A-F accountability system, created by Morath.

Marshall and Flores were the only two trustees to vote against the resolution, citing their hesitation to oust the grading system before it rolled out. Kirkpatrick left the meeting determined to run for office. Later in the campaign, she cited Marshall’s vote that day as proof of his support for vouchers.

Marshall bristled at this accusation during an interview before the 2017 election, countering that he had been involved in efforts to stop voucher legislation.

“I don’t know how I possibly could have been more clear about it,” he said. “To debate with me on an issue we agree about is disingenuous.”

Marshall insists that he’s a public education advocate, not attacker. He says he grew up with a single mother struggling to make ends meet and “was fortunate enough to get into Greenhill.”

[Extra feature: Where do DISD trustees send their children to school?]

“To be honest, I’m trying to create the same kind of educational outcomes that I enjoyed in Greenhill at DISD,” he says. “Every kid deserves that same kind of lift up and potential that I got and my kids get.”

But “change is hard,” Marshall says, and education is “a system that has resisted change for a long time” and has “fierce defenders of the status quo.”

“Most reformers I talk to prioritize student outcomes above any other motivation,” Marshall says. “The folks that prioritize evidence and results and data, we’re on the right path, and if we continue down that path, we’ll change a lot of lives, so we want to stay the course.”

Kirkpatrick, a Lakewood Elementary mom who says she’ll run again for the board in 2020, doesn’t buy it. Her campaign website continues to host the blog she launched when she decided to run. Each post questions and casts doubt on “the corporate education reform movement” that “promotes underfunding public education, A-F, vouchers [and] ultimately leads to the privatization of public education.”

Enough people agreed with Kirkpatrick or were given pause to cast more votes for her than for Marshall in the general election. If it weren’t for a disgruntled former DISD employee who filed to run — and who received 3 percent of votes despite no campaigning or fundraising — Marshall and the reform community might have lost outright.

Kirkpatrick and members of her campaign team recently launched a nonprofit, the Coalition for Equity in Public Education, to “stand up to privatizers currently threatening education as we know it.”

The problem isn’t a lack of knowing how schools and teachers are performing, Kirkpatrick argues. “Your outcomes for children are predicated on whether they’re wealthy or poor,” she says. The problem for urban schools, she believes, is poverty compounded by the underfunding of public education. The state spent $2.5 billion last year on charter schools, which are publicly funded but privately run, she says.

“What could we be doing with that money in failing schools?” she asks.

The people who need to be driving policy decisions are experienced educators, she says, not data wonks, business executives and Teach for America alumni with little classroom exposure.

Montage: Young recruits get out the vote

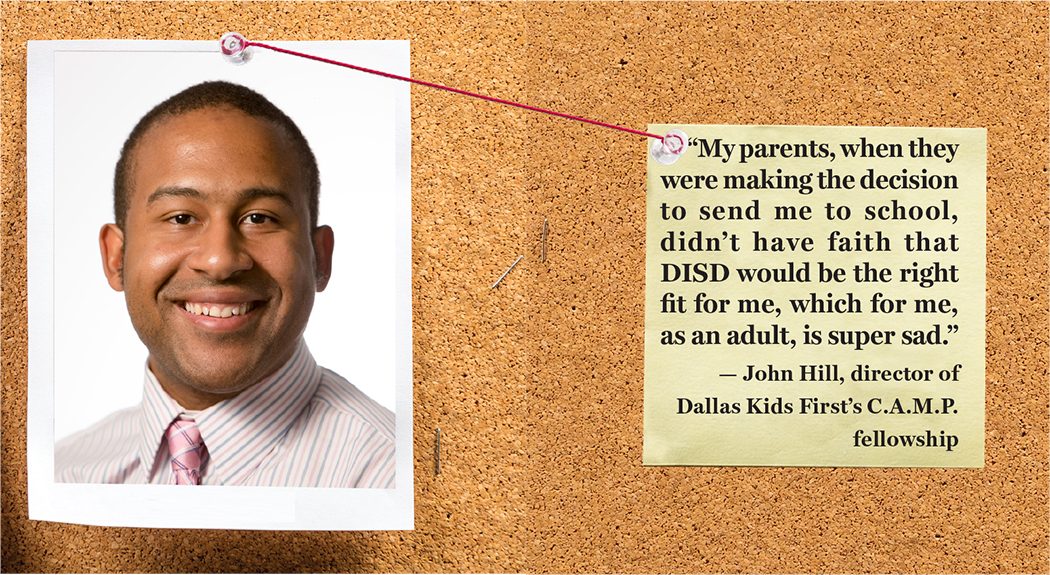

The big money donors don’t bother John Hill. He’s one of the TFA alumni distrusted by people who distrust education reformers. He left DISD’s Pinkston High School after his two-year TFA contract and went to teach at Jesuit College Preparatory, his alma mater.

But Hill, like many TFA alumni, never left DISD.

During his tenure at Pinkston, he launched a blog and podcast, Turn and Talks. The content has segued from teacher musings to political activism as Hill heads up the Dallas Kids First “C.A.M.P.,” an eight-month fellowship for 20 or so young recruits who commit to spending 100 hours campaigning for the PAC’s endorsed candidates.

This, even more than money spent on mailers, polling and advertising, makes the reform effort a force.

Hill, who lives in Oak Cliff behind the Tyler-Vernon DART station, says his parents attended DISD high schools in the ’70s, during the early years of desegregation. His father graduated from South Oak Cliff, and his mother was among the first black students bussed to Carter. Hill would have attended Roosevelt, but “my parents, when they were making the decision to send me to school, didn’t have faith that DISD would be the right fit for me, which for me, as an adult, is super sad.”

His grandmother spent her career teaching at Marsalis Elementary School, and her retirement savings paid for Hill’s Harvard education, so “I still have a lot I owe to the district,” he says.

Hill says he saw firsthand in 2016 that money doesn’t win elections. Only two of the four reform-funded candidates won their races, and one of those was Marshall’s runoff. He also felt deflated by the traditional model of campaigning — “show up six weeks out from an election and tell people you don’t know what’s good for them,” he says. Keeping voters engaged requires more, he believes, and C.A.M.P. is his solution to that problem.

Hill mobilized the C.A.M.P.ers, as he calls them, in the month between the District 2 general election and runoff between Marshall and Kirkpatrick last year. They spent 4,000 hours knocking on doors and talking to voters. According to Hill’s calculations, C.A.M.P.ers were responsible for 3,200 votes, including 900 people who hadn’t voted in any of the three prior elections with Marshall on the ballot.

The result: Marshall went from nearly 300 votes shy of Kirkpatrick in the general election to more than 3,000 votes ahead of her in the runoff.

Close-UP: ‘The gray-haired one over here’

A trendy bar just south of Downtown seemed an unlikely setting for a political action committee to host its kick-off for the 2018 DISD board election cycle. The crowd of diverse young professionals who gathered at Mac’s Southside seemed even more unlikely.

Melissa Higginbotham, describing herself as “the gray-haired one over here,” stood out. She started working for the Dallas Kids First PAC when it formed in 2011 after her children graduated from the Booker T. Washington arts magnet and W.T. White.

“I was pleased with my children’s education in Dallas ISD, but I also read the Dallas Morning News and thought, ‘Wait, there are some areas where it might not be so good,’ ” she recalls. Though the PAC’s membership is broader than the crowd at Mac’s would suggest, she says, “it’s exciting for me to have folks who don’t have kids yet who are investing in our city and our school system, so that when they do, they feel comfortable putting their kids in DISD.”

Higginbotham chafes at Dallas Kids First being identified as a PAC. It carries “somewhat of a negative perception,” she says. “But we did want to be able to endorse candidates and come up with a system that shared more information about candidates and why they were endorsed. That just wasn’t happening [in 2011].”

[Deleted scene: No pay for play at Dallas Kids First]

They look for trustees who “are really seeking solutions,” Higginbotham says, and who support “things that have national research and national data behind them.”

Both Henry and Turner were at Mac’s Southside for the kick-off. Given the money the PAC has and the C.A.M.P.ers ready for action, an endorsement could be crucial.

Nutall didn’t attend the kick-off. No one, not even her, believes she will get the endorsement. At one point she found favor with reformers, but now she’s “in the outhouse,” she says, because she argued and didn’t always vote the way they wanted.

Without naming Nutall, Higginbotham notes that when Dallas Kids First interviews incumbents, “we ask them, ‘What policy initiative are you most proud of?’

“If they cannot answer that question right off the tip of their tongue, that’s hard for us.”

Flash cut: Race dominates a district race

As of press time, only one DISD trustee race was contested. Neither North Dallas’ Edwin Flores nor Far East Dallas’ Dan Micciche had drawn opposition.

In District 9, however, the race began last summer.

Henry, who filed to run against Nutall three years ago then withdrew, posted initial campaign donations last July, signaling that this time, he was serious. In September, Marshall introduced Turner to the invitation-only Dallas Breakfast Group, which functions as the incubator of northern Dallas politics. Then he and Flores indicated their support for Turner in the District 9 race — despite the fact that the election was eight months away and Henry was sitting in the room.

The deliberate introduction caught the attention of southern Dallas Trustee Joyce Foreman, who, in a Facebook post blasting Marshall for being “hateful” toward the three African-American trustees, also noted that “he has a hand-picked Negro that he is supporting” in the race against Nutall.

Foreman’s rant against Marshall was the result of Marshall’s repost of Schutze’s column, the headline claiming that “The Worst Enemies Poor Black Kids Have Are Black Dallas School Board Members.”

“How do people think black folks are going to even embrace you when you have a writer saying the three African-American trustees are Public Enemy No. 1 to black children?” Nutall asks.

“You don’t get the right to tell me how to respond when you mistreat me … when you say whatever about me, and you say it in the newspaper, and you say it on Facebook,” she says. “It’s been some pretty ugly stuff. And then you want me to say, ‘Oh, can’t we all just get along?’ ”

Nutall believes her role is to fight for her community. The problem, both Henry and Turner believe, is that she no longer represents the community or its best interests.

They might not have entered the race if it weren’t for last August’s board vote on a tax-ratification election, which was the focus of Schutze’s instigating column. The election would have asked voters for a property tax increase with most of the money coming from north Dallas property owners and going to southern Dallas schools. Nutall, Foreman and Blackburn supported a small increase but rejected the larger tax hike reformers wanted.

“This was literally about ego, power and control,” Turner said after the vote, this time pointing the finger at the southern Dallas trustees rather than the north Dallas agenda he fought against during the home-rule effort. He’s moved past that debacle but others haven’t, he says.

“We have to decide to heal,” he says. “I think right now with the current board, it’s not going to happen. That’s why you have to have change. There’s too much divisiveness on the board, and you have to have someone that’s willing to work with everybody.”

Henry, too, saw the distrust rear its ugly head again. “To think that black trustees are sabotaging kids that they serve … I find that offensive in my most tolerant state. You’re substantiating those concerns and justifying their distrust,” Henry says.

Yet he’s frustrated that “they can’t see a good thing when it’s in front of them because they distrust each other. This gate keeping system is hurting District 9. It’s hurting the whole city.

“I think we have to use the past to inform every decision we make, but we shouldn’t let the past dictate the future.”

Corrections: The original version of this story incorrectly stated that Todd Williams opened his own Uplift charter school, and that District 1 Trustee Edwin Flores and District 2 Trustee Dustin Marshall endorsed District 9 trustee candidate Ed Turner.