Their memories didn’t always serve them, and sometimes they mistook their interviewers for government officials who could help them receive pensions, so their recollections could’ve been presented “with rose-colored glasses,” the Library of Congress states. Besides that, not all of the writers were experienced or reliable interviewers. Some were indifferent to the truth and may have censored the stories.

The Library of Congress made the full narratives and photos available in 2002, and they can be found at loc.gov. These are snippets from some of the narratives of former slaves who lived in Dallas, including one who lived in Oak Cliff’s Tenth Street Historic District.

In Texas, the end of slavery wasn’t announced until June 19, 1865, two-and-a-half years after the Emancipation Proclamation took effect, on Jan. 1, 1863. After the Civil War, some slaveholders moved to Texas in order to keep people enslaved.

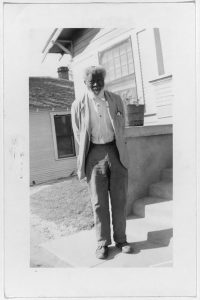

Stated age: About 82

Residence: 1120 E. Tenth St.

Hursey was born in Louisiana, and his family was sold to Jim Boling of Red River County, Texas, when he was a child. The day he left the plantation with his parents and siblings, Hursey recalled that Jim Boling called him over and gave him a cup of sweet coffee. “He thought considerable plenty of me,” Hursey said. His mother and father worked for farmers after emancipation, and the children had to work too. Hursey attended school for one week and taught himself to read with the help of friends. He became a preacher and at the time of the interview, described himself as “head prophet of the world.”

Stated age: 77

Address: Owned a restaurant at 1301 Marilla St.

Johnson was born near San Marcos, Texas, and she said she was so little when emancipation came that she hadn’t known she wasn’t free. She recalled making a “playhouse” with white and black children, sweeping a patch of ground under the trees and playing with broken pieces of pottery. After emancipation, Johnson, her mother and siblings worked in cotton, corn and wheat fields. She had 10 children and never learned to read or write, but her interviewer noted that she spoke without dialect. She said she never cared about religion until she became very ill at about age 15 and she saw a heavy white veil over her bed. After that, she was saved. “I’m looking to the promise to live in Glory after my days here is done.”

Stated age: 97

Residence: Good Street, which later became Good-Latimer Expressway

An intro to her narrative states Wilson was blind and bedridden, but the photo shows her standing up outside in a fur coat. A cruel mistress, who often tied her down and beat her as a child, sometimes rubbed snuff in her eyes, and she believed that’s why she lost her eyesight. At about age 8, she was forced out of her mother’s cabin and had to sleep at the foot of the woman’s bed.

She says her father was born free, a “full-blood Creek Indian,” and eventually he was forced off their homestead. Wilson, her siblings and mother belonged to a man named Wash Hodges of Kentucky. Her mother later was forced to mate with an enslaved man and bore 19 children, according to Wilson. The children would be sold off while Wilson’s mother was working in the fields, and she would return to find her child stolen.

Wilson grew up near Mammoth Cave and said she used to play inside that natural wonder as a child. But most of her time was spent spinning cloth. She was married and told to start having children at around age 13.

“Now, when I was little they was the hardest times,” she said. “They’d nearly beat us to death.”

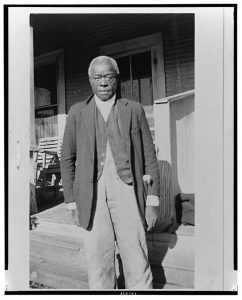

Born: About 1855

in Selma, Alabama

Residence: Good Street

Moore’s master, Tom Waller, moved to Mexia, Texas, during the Civil War to avoid the emancipation of slaves. As a boy, Moore was a shepherd, and he recalled being hungry all the time. Occasionally, he was allowed to go to church on Sundays, but they had a white preacher who told them to obey their masters in order to get into heaven. They were allowed to sing but had to pray in secret, Moore said.

Moore describes Tom Waller as a sadist: “He just about had to beat somebody every day to satisfy his craving,” he said. Waller tied men to the ground and would force another slave to hold their heads into the dirt while he beat their backs with a bullwhip. The children were told to watch. Waller once beat Moore’s mother’s back with the teeth side of a handsaw, and she bore the scars for the rest of her life.

After emancipation, Moore, his mother and siblings worked on farms in the Corsicana area. He never went to school, and the school his brother, Ed, attended was destroyed by the Ku Klux Klan. Moore said all three of his own children attended school.