Photos courtesy Jerry and Carmen Rhome

From 1942 until 1960, in Oak Cliff, Rhome was burning. Jerry Rhome, that is.

He was born at Methodist Hospital and attended Lida Hooe Elementary School, where his mother was later a teacher. The Rhome family lived on Sunset Street and were members of Sunset Church of Christ. He shopped at Wynnewood Village and on Jefferson, ate at Austin’s Barbecue, munched on ice cream at Polar Bear and bought his school supplies at Skillern’s.

On neighborhood streets — riding his bicycle at lightning speed or careening down Oak Cliff terraces and slopes — the Oak Cliff youngster “burned”. Jumping and leaping, crashing and dashing, Rhome, a self-described daredevil, never stopped.

Through the decades, he has broken both his arm and his leg, plus four of his fingers. He has had three concussions, two separated shoulders, two torn rotator cuffs, and serious knife cuts and gun damage (from blanks), both to his left hand. Rhome says he injured himself continuously in his quest to find “adventure” everywhere he went.

“I was a wild kid,” he says.

But it didn’t stop there.

By his freshman year, Rhome was quarterback of the 1956-57 W.E. Greiner Yellowjackets. He also excelled on the basketball court and baseball diamond, shining on defense and offense in both sports. From that point on, he says, “I never looked back.”

However, it was the football field that held his future.

In fall 1958, this Oak Cliff high school athlete’s performance exploded on the sports scene, and people throughout the state took notice. He was a passing-punting-running dynamo.

During Rhome’s years with the Sunset Bison, his father, Byron Rhome, mentored his son as Sunset’s head football coach. The impressive stats racked up by Rhome, who naturally took the helm as team captain his senior year, led to his induction into the Texas High School Hall of Fame. (Turn the page for a rundown of Rhome’s stats.)

But he also continued his involvement in other sports. At the conclusion of football season, he played for the Bison hoopsters and, in the spring, played outfield for the baseball team, garnering top honors in both of these sports, as well.

After graduation he quarterbacked for the Southern Methodist University Mustangs but transferred at the end of his sophomore year to the University of Tulsa — a perfect fit for his talent package. At the helm for the Hurricane, he emerged as a true phenom, and set heads spinning with his ramblin’-scramblin’ performance.

According to Rhome, teammates affectionately called him “The Rhomer” — a nickname he picked up during his high school days, “because they said I roamed all over the field.” The tag remained even during his professional years.

In college, as in high school, Rhome dominated the football field. In just one example, the Hurricane’s game with Louisville, Tulsa came out on top 58-0 with Rhome scoring all 58 points, running and passing. No shabby performance.

Out of 326 passing attempts during Jerry Rhome's senior year at the University of Tulas, he socred 32 touchdowns and threw only four interceptions.

While at Tulsa, he set 18 NCAA records, a one-player tally that will probably never be matched or broken. And all during his senior year.

In a Nov. 16, 1964 issue of Sports Illustrated, writer John Smith made the following comments:

“The shows revolves around Jerry Rhome.

“He works hard at learning to pass when things are not going right, throwing off balance, while falling, on one knee, or with the wrong foot forward. He throws to all distances and he knows when not to throw.

“[Against Louisville] Rhome threw seven touchdown passes, a national record. In another, two weeks ago, he completed 35 of 43 for 488 yards, and four more national records fell. This modest feat occurred against Oklahoma State, a favored team that went into the game with the second best pass defense in the U.S. and came out with a devastating 61-14 loss.”

In the 1964 Heisman Trophy race, Rhome finished only 74 votes behind the winner, in the closest poll ever (to that date). The player who finished third — a whopping 477 votes below — was none other than six-time Pro-Bowler Dick Butkus.

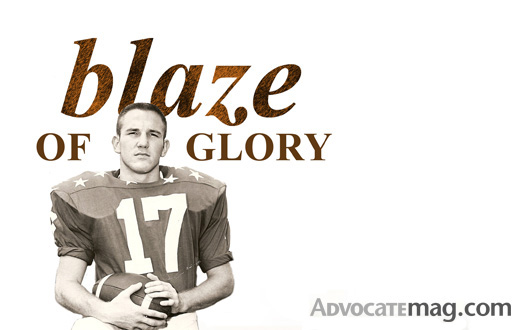

The University of Tulsa retired Rhome’s No. 17 jersey, followed by his induction to the Oklahoma Sports Hall of Fame.

Drafted in 1964 by his hometown NFL team, the Dallas Cowboys, Rhome was the team’s backup quarterback for two seasons. While in that role, he managed to survive the infamous 1967 Ice Bowl game played in Green Bay, Wis., describing the event (played in temperatures of 13-25 degrees below zero with a wind chill of 36 degrees below zero), as “brutal.”

“It got a lot colder,” he added, “when Green Bay scored on the last play of the game to win the championship.”

Rhome went on to quarterback for the Browns, Oilers and Rams. Then he spent one year in the Canadian Football League before a rotator cuff injury ended his playing career.

However, the former Oak Cliff kid quickly switched gears and jumped into coaching. He began at his alma mater in Tulsa, and later coached for 10 different NFL teams, guiding both quarterbacks and wide receivers. For 17 of his 25 years in professional coaching, he served as an offensive coordinator. He coached both Pro-Bowlers and Super Bowl MVPs, among them Joe Theisman, Troy Aikman, Kurt Warner, Doug Williams, Warren Moon and Michael Irvin.

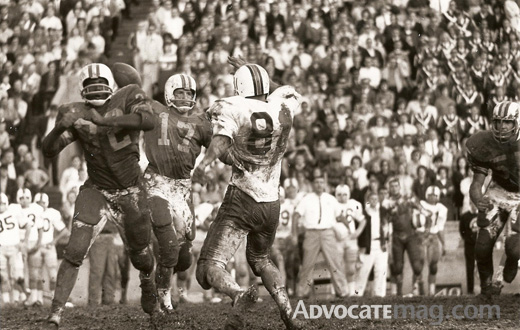

Rhome takes a breather on the sidelines during a University of Tulsa game. His record-setting senior year put him in top competition for the Heisman Trophy.

To top it all off, as a member of the Washington Redskins coaching staff, Rhome was awarded a Super Bowl XXII championship ring — a ring he wore on a Sept. 25, 2010, visit to Sunset High School where he participated in a photo shoot featuring 74 years of Sunset quarterbacks.

Although he’s had a stellar career and ranks at the top of the list in professional coaching, in all respects Rhome is still a down-home Oak Cliff boy, proud of where he was raised.

“We were very lucky to grow up in Oak Cliff in the ’50s through the ’70s,” Rhome says. “It was sort of like a movie: clean, fun, cool hangouts, not dangerous and lots of adventure.”

“Every January, males of our ’60 class gather on a ranch for a four-day blast out in West Texas,” Rhome says. “And, hundreds of classmates from ’56-’70 have newsletters, Facebook [pages], emails and stay in contact. [There are] many gatherings in the Dallas area, with golf, parties, etc.”

Rhome visits Oak Cliff regularly, and on a recent trip he experienced a new “first”.

After receiving a coaching request from a local football mom, Rhome scheduled a private coaching session with the woman’s child — who turned out to be her daughter.

“Actually, after working with the girl for a while,” Rhome says, “I suggested to her mother that the young lady spend more time with her books and not playing football. I don’t think she was very happy with my evaluation, though.”

Rhome currently resides near Atlanta with his wife, Carmen, and spends his time coaching privately, giving inspirational speeches, holding camps and coaching clinics, staying in contact with friends in Atlanta and Dallas, and traveling a lot. He works out, attends church, goes to movies, and plays both golf and a lot of pool.

“I do all those things I didn’t get to do when I was putting in 18-20 hours a day working in the NFL,” he says. “I’m in good shape and healthy, except for old injuries.”

At age 68, you’d think Rhome’s football playing days would be over. But not so.

He continues playing regularly, still quarterbacking in the NFL — that’s the Neighborhood Football League, if you will. Performing at the helm of what he’s tagged the “Dream Team” — made up of 7- to 17-year-old neighborhood boys and girls — Rhome is still burning.

Accidental beginnings

The crash that could have ended his future instead marked the birthplace of his career.

In summer 1955, 13-year-old Jerry Rhome and his friend, Fred Ferguson, were riding bicycles close to the Sunset High School practice field — located, both then and now, behind and north of Lida Hooe Elementary School. Barreling forward at his usual break-neck speed, Rhome began racing his friend, flying north up Franklin Street toward the corner of Franklin and Alden. The ultimate destination was still several blocks away.

But fate had another ending.

Last fall Rhome, back, returned to his old stomping grounds to meet with former Sunset High quarterback Glenn Brooks, class of 1937, and current players Michael Granado andRaymundo Garcia. Photo by Jordan Kokel.

Losing control of his speeding bicycle, both Rhome and the bike jumped the curb, slamming the young teenager’s still growing body into a large tree on the northeast corner of the Franklin-Alden intersection. Rhome remembers the event as the time he “wrapped” his leg around a tree, certainly no experience for the faint-of heart.

Fortunately, the injured boy’s father, Byron Rhome, was close by, working a summer job that included delivering baseball bats to area parks. The elder Rhome had seen his share of serious football injuries during his own days as a high school and college athlete, as well as in his primary job: teacher and head football coach for the Sunset Bison.

Knowing exactly what to do, Dad Rhome removed bats from one of the elongated shipping boxes and used the cardboard container to make a splint for his son’s leg. After reaching Methodist Hospital, Rhome Sr. put in a call to orthopedic surgeon Dr. P. M. Girard, developer of the Carroll-Girard Screw, a device designed for the repair of severe compound fractures. Girard told Rhome’s parents that he couldn’t guarantee success, but he did think the screw would work.

And, work it did!

After spending four and a half months in a full body cast, the eighth-grader was ready to go by mid-basketball season. And the rest, as they say, is history.

The next fall he quarterbacked for the W. E. Greiner Jellowjackets. Then, as a forward on the basketball team, he led the city in scoring. Moving to Sunset High School, he set records and impressed fans, ending his career there with spots on the all-city and all-state first team roster, and as first team high school all-American. He went on to play in college, finishing his career with 18 NCAA records and as the runner-up for the 1964 Heisman Trophy, among numerous other awards. (Read “Blaze of glory” on page 22 for an extensive detailing of Rhome’s achievements.)

An eight-season NFL quarterback, a Super Bowl XXII championship coach, a personal quarterback coach and an all-around good guy, Rhome accomplished all this with, as a result of the bicycle accident, one leg an inch and a half shorter than the other. Amazing.

But at the time of Rhome’s accident, one item probably went unnoticed: its ironic location, on the cusp of the Sunset practice field — the very place that shortly afterward gave Rhome his send-off to the highest level of fame, accomplishment, awards and recognition that he could have imagined. Without the gamble made by his parents and the surgeon, and the subsequent determination of the young athlete himself, it all could have ended there, on the corner of Franklin and Alden.

Instead, it’s the place where everything sort of began. In a phrase — Rhome’s own Field of Dreams.

Granted, there were no rows of corn with old-timey baseball players emerging, but there were rows of football players. And, like the movie, Rhome’s father was there, too. For decades, this bit of turf has continued to be a place where young athletes have had the opportunity to dream a bit, of futures and careers, and possibly enjoy a brief moment in the limelight.

All this to say, the next time you have your own “wrap your leg around a tree” experience — and you’re jolted, dazed and don’t know what to do — you might want to remember a 13-year-old Jerry Byron Rhome racing through Oak Cliff on his bicycle, colliding with a tree, and then being corralled for months in a full-body cast. Do what he did, although he probably didn’t recognized it at the time: Look a few yards away from where you “crash”. You may have landed, inadvertently, beside your own field of dreams.

Lift your head a bit and look for the possibilities that may lie straight ahead. Sometimes, unknowingly, your future may be only a few yards away and staring you in the face.

For Jerry Rhome, it certainly seems to have happened that way.

Stats

Proudly donning their Sunset letter jackets are all-city players Charles Marshall and John Beall with Rhome, who achieved all-city, all-district and all-state honors his senior year.

It’s impossible to sum up Jerry Rhome’s career, but here is a brief overview of his high school and college achievements:

As a Sunset Bison:

· Racked up 3,440 total yards of offense, both passing and rushing

· Completed 182 of 329 tosses and scored 35 touchdowns

Senior year at Sunset:

· Kicked 14 of the team’s 16 extra points

· Passed for 28 of 30 two-point conversions

· Earned first team, all-city and all-state honors

· Named a high school all-American

· Nabbed the 1960 Bell Award (Dallas County Player of the Year)

· MVP in the North-South All American Game

· Inducted into the Texas High School Hall of Fame

As a University of Tulsa Hurricane:

· Threw for a total of 4,779 yards and 52 touchdowns

Senior year at the University of Tulsa:

· Racked up 2,870 of the yards

· Scored 32 touchdowns off his 326 attempts with only four interceptions

· Beginning with the second game of the schedule, threw no interceptions for the remainder of the season

· Achieved the record for most touchdowns in a game and in a season, and most passes without an interception in a year and in a career

· Sports Illustrated player of the year

· Associated Press player of the year

· Oklahoma Sportsman of the Year

· College Football Hall of Fame member

· University of Tulsa Hall of Fame member

· Garnered the 1964 Sammy Baugh Award presented by the Touchdown Club of Columbus to the nation’s top collegiate passer

· Won the 1964 Walter Camp Award for being the national passing winner

· Named to nine different all-American rosters including the NCAA

· Led the nation in passing and total offense

· Named the 1964 Bluebonnet Bowl MVP