Photography by Corrie Aune

An official YouTube channel from Southern Methodist University delivers daily news on topics such as real estate, schools, City Hall, celebrities and the Dallas Cowboys.

It’s just that these stories are going digital about 50 years after they first aired.

Two guys in a sub-basement beneath the Greer Garson Theater at SMU spend five days a week restoring, digitizing and cataloging film and video archives containing old news stories from WFAA and KERA, plus the odd 16-mm reel that could contain a formatted-for-TV movie, a student orientation film from the 1960s, or often a surprise, since not every old label is correct.

It’s like opening a mystery grab-bag every day.

The vault at the G. William Jones Film and Video Archive, kept at a constant 55 degrees Fahrenheit and low humidity, holds a total of about 5,200 films on 16-mm and 35-mm.

In the vault are fine-grain masters of the TV show Death Valley Days, which ran an astonishing 452 episodes, from 1952-1970; a rare 1926 Alfred Hitchcock feature, The Pleasure Garden, a silent film about chorus girls in London; and the Tyler, Texas Black Film Collection, which contains about 14 features entirely directed, produced and acted by Black filmmakers for Black audiences between 1935-1956.

Much of the 35-mm collection consists of “B-movie junk,” anything from cheesy horror to soft-core, with titles such as Disco Godfather and CB Hustlers.

They also have 35-mm versions of Disney’s Pinocchio, Easy Rider and Hard Day’s Night, for example, plus an impressive collection of Italian and French new wave paragons.

“But those are available on BluRay, and anyone can watch them,” says Hamon Arts Library moving image curator Jeremy Spracklen. “A lot of the stuff we have that you’ve maybe never heard of, we have the only copies. They’re not great movies, but they’re rare.”

The entire archive of the bygone production company best-known for the movie Benji is among the collections.

Vintage news

There’s also a history of Dallas told through the lens of TV journalists.

Curator Spracklen and Scott Martin, who has a master’s degree from the SMU film school, upload four items every day: a full roll from exactly 50 years ago, a KERA clip and a WFAA clip, then either another KERA clip or something from another collection.

Their biggest YouTube sensation is a film of Jimi Hendrix arriving at Love Field in April 1969, which has almost 363,000 views. Footage of a 1974 baseball fight between the Texas Rangers and Cleveland has over 166,000 views.

Previously unseen footage of Martin Luther King Jr., uploaded four years ago, and a 1970s profile on journalist Bob Ray Sanders, uncovered this year, are among the team’s favorite finds. And they say this daily time travel can be rewarding.

“We’ve heard from people who say, ‘This is my grandfather, and I’d never heard his voice before,’” Martin says.

Spracklen and Martin have become experts on Dallas history by osmosis.

“It’s cyclical,” Martin says. “And we were dealing with some of the issues in 1970 that we’re dealing with now.”

The KERA, channel 13, archive offers a history of video formats, which arrived neatly organized. Digitization of that collection began about two years ago. Their stories from the 1970s dive a little deeper into topics like poverty and politics in Dallas.

The WFAA, channel 8, film archives came in cans that were sometimes accurately labeled. Uploads of those have been ongoing since about 2015, and they contain work from former local reporters Tracy Rowlett and Bill O’Reilly.

The vault also holds the KDFW, channel 4, archive. Those were stored uncarefully and are not well cataloged. The team expects to take years to restore and upload them, a project they haven’t yet begun.

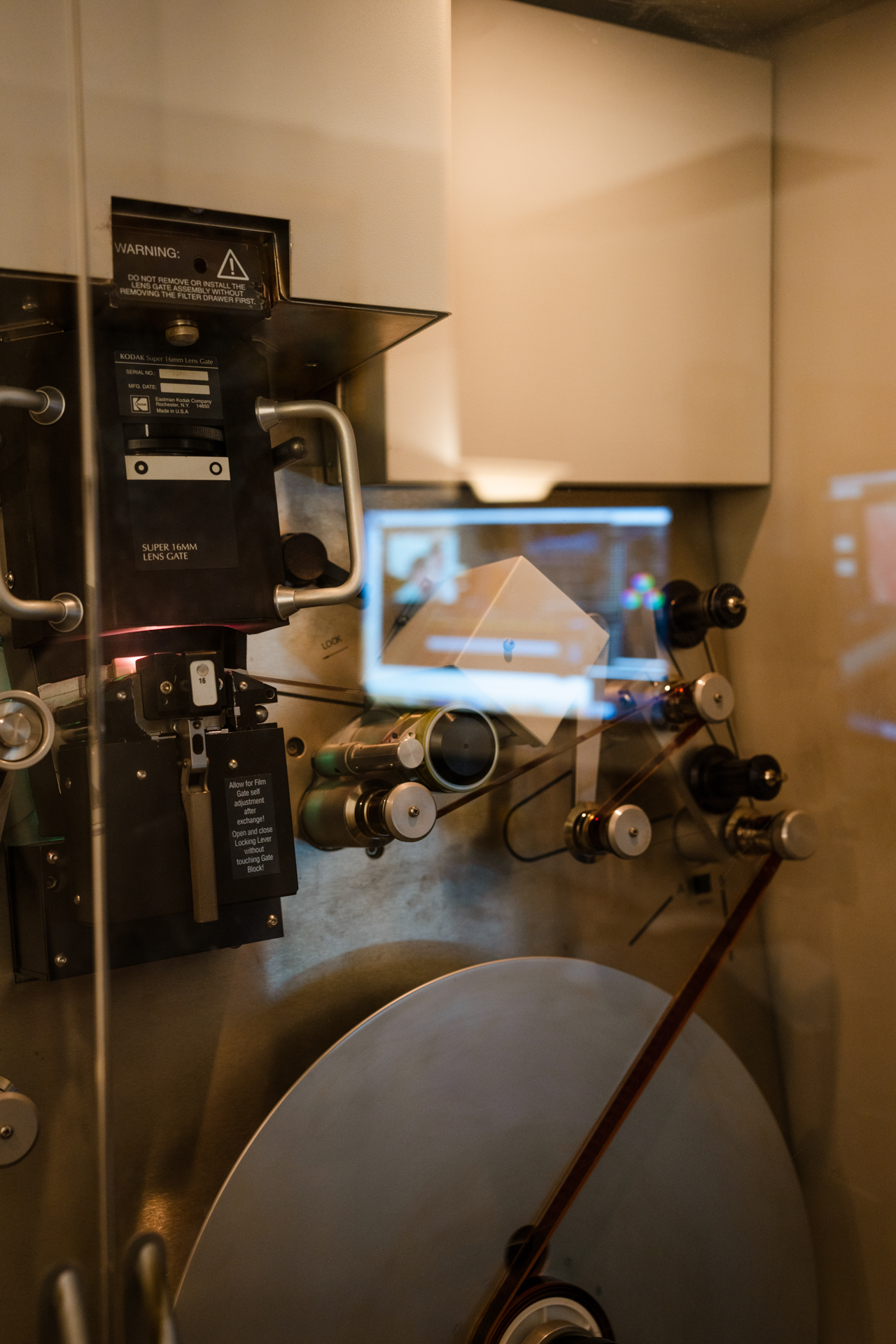

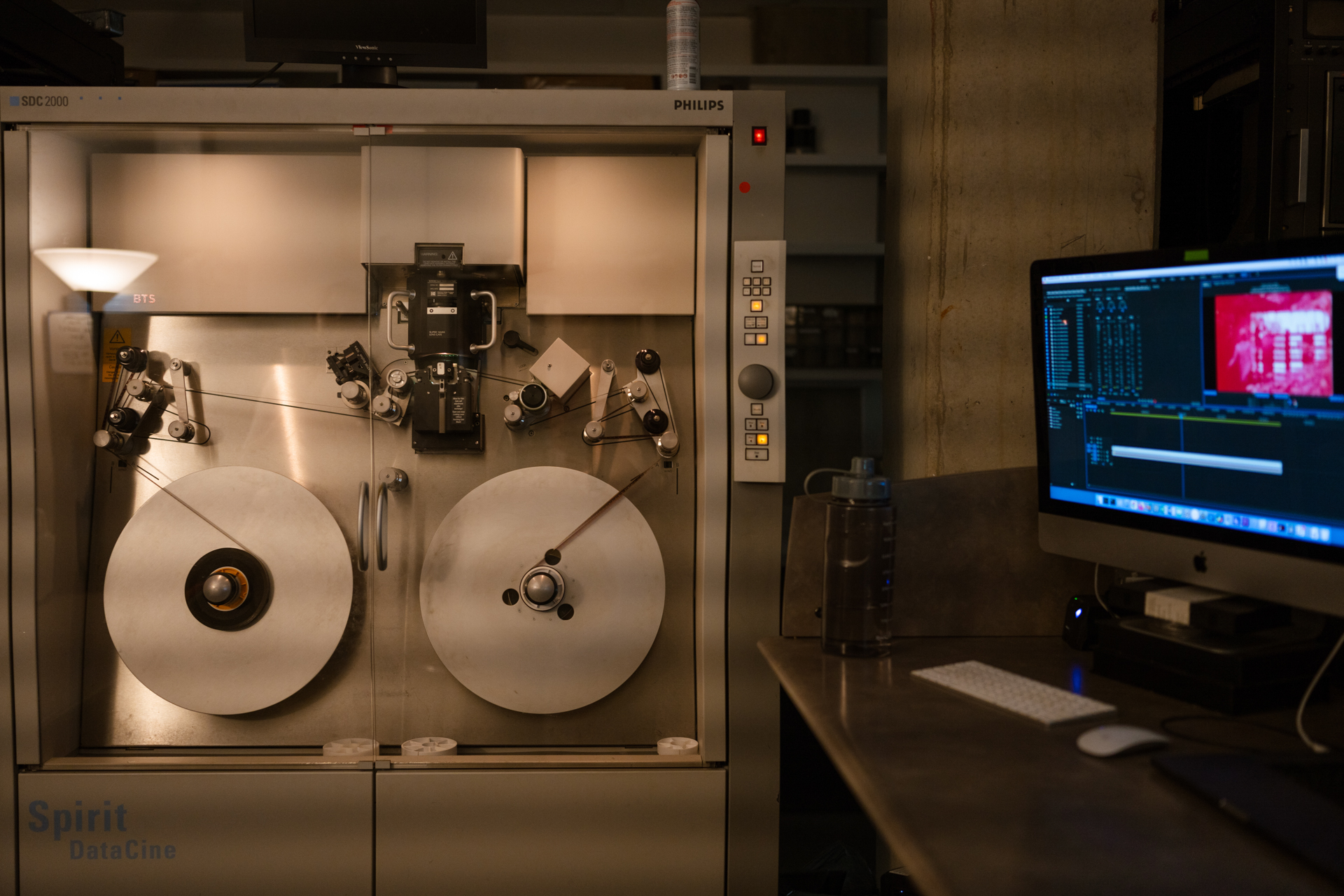

In the first step of digitization, Martin uploads a 16-mm film, for example, onto a reel-to-reel device. He feels for the splices and determines if they will hold, or if he needs to restore them.

If not, the archive has a machine that will play the film and digitize it. Martin then works on adding metadata to YouTube as well as the analog film.

The team uploads four items from the collection every day: a full roll from exactly 50 years ago, a KERA clip and a WFAA clip, then either another KERA clip or something from another collection.

In the vault

Besides moving images, the archive also contains hundreds of original movie posters, most of which were donated by film historian Jeff Gordon, who moved to Dallas shortly before his death in 2020 but had a relationship with the Hamon Arts Library for years prior.

The film and video collection started in 1970 to serve the film school and was named for film collector G. William Jones in 1995.

“It started as a teaching collection for the film school,” Spracklen says. “At the time, they didn’t have DVD; they didn’t have VHS. If you wanted to show a film, to film students, you had to have a print.”

Some came from film exchanges that closed, such as the Tyler Black Film Collection, named for the city where it was found in the 1980s. The Sulphur Springs Collection was donated to the archive in 1993 after someone in that East Texas town found eight reels containing 33 “pre-nickelodeon” films dating from 1898-1906.

The vault also contains a lot of 16-mm reels of unknown origin that pertain to Dallas history, such as footage of the Velvet Underground performing at White Rock Lake, which they digitized two years ago.

Occasionally the footage makes its way into documentaries, such as the 2021 miniseries The Lady and the Dale.

Their Velvet Underground footage was part of a documentary shown at the Canne and Telluride film festivals.

The USA Film Festival originally started as a mechanism for the G. William Jones Film and Video Collection, and films from the collection sometimes show as part of local film festivals and events.

While screenings of the archive’s rare films may be unusual, Spracklen and Martin are eager to publish their digital news archives.

It’s rewarding to uncover footage of big news events and celebrities, but the less glamorous stuff is fun too, Spracklen says.

“It’s the human-interest stories,” he says. “The everyday life that’s happening, and it was being covered in the news.”