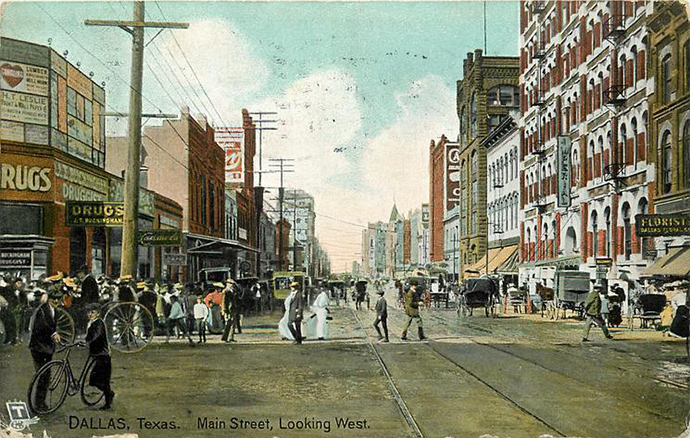

Raphael Tuck & Sons printed at least 31 postcards with images of Dallas. Main Street, 1908, looking west.

Christopher Tuck of Stevens Park found an album filled with old postcards at an antiques show years ago. The cards were from a young man in the south of England who wrote to his sweetheart in London each week to let her know what time his train would be arriving for their Saturday visit.

Call it a very early version of text messaging.

Before telephones were widely available, postcards were an inexpensive way to communicate short messages.

That book of postcards was more than just an insight into history; it was part of Tuck’s family history.

Tuck is a descendant of the man who started the world’s preeminent postcard company.

Raphael Tuck started a publishing company, Raphael Tuck & Sons, in London in 1866. Raphael Tuck is Christopher Tuck’s great-great-grandfather.

The company founder, who was born in Prussia, didn’t invent postcards, but he made them popular, and his company set a high standard for quality in printing.

In 1900, at the height of a global postcard boom, the company had about 4,000 postcard designs available.

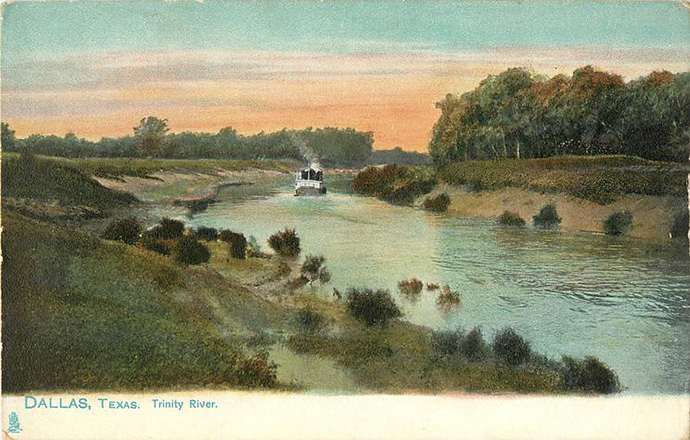

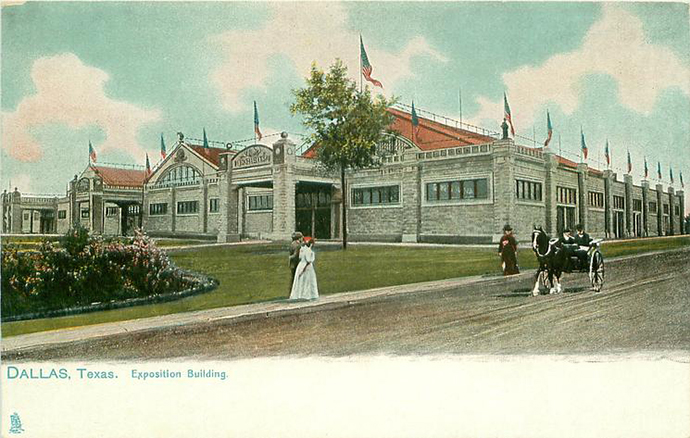

Raphael Tuck & Sons published at least 31 cards depicting Dallas, including one of Lake Cliff Park, in the early 1900s.

Postcards were extremely popular as a way to communicate and as keepsakes. Imagine traveling to Dallas by train from the sticks of Oklahoma to see the great State Fair of Texas, for example. The only way to show the sights to one’s friends and relatives back home would be to purchase picture postcards, which were inexpensive and cheaper to mail than a letter.

Raphael Tuck & Sons also is credited with making Christmas cards popular. In 1880, the company launched a contest offering 5,000 pounds in prizes for the best Christmas card designs.

“It was a way for them to gauge people’s ideas about Christmas,” Tuck says.

Some 5,000 people submitted their artwork into the contest.

The best designs were shown in a London gallery, and after that, Christmas cards became the norm in England, and the tradition grew from there.

Commerce Street, 1905, facing west from Griffin. There now is a McDonald’s where the Dorsey Hotel was.

The company printed more than just cards. Its products also included children’s books, paper dolls, tourism pamphlets, and educational and religious wall hangings, among other printed materials.

But cards were their bread and butter. The popularity of postcards and Christmas cards brought in new revenues to the British Crown through postage sales. Because of that, King Edward VII in 1910 created the Tuck Baronetcy. Upon the death of his father, Christopher Tuck will inherit the baronetcy and could employ the title “sir.”

Tuck’s mother, born Louise Renfro in San Angelo, was a fashion model who married the postcard heir Sir Bruce Tuck in 1951. They moved to Jamaica when Christopher and his brother were little. Christopher also has lived in London, Montreal, New Orleans and San Angelo. He is a retired systems engineer.

The Raphael Tuck & Sons London headquarters, a five-story building with a view of St. Paul’s Cathedral, was destroyed in The Blitz of 1940. Among the devastating losses were decades of original artwork, about 40,000 designs. The company continued to operate after World War II, but by then, telephones were ubiquitous. Cameras were becoming more affordable and user friendly. The company never regained its former success and closed in the 1960s.

Christopher Tuck says his father, now in his 80s and living in England and Italy, never has shown interest in his family’s history. Christopher’s older brother, Richard, who died in an accident last year, also was uninterested in family history or antiques.

So after his mother’s death, Christopher inherited a houseful of antique furniture and paintings. His Stevens Park home, which he chose because of its pre-1950 construction, feels very English, with its oil paintings of ancestors and delicate Victorian furniture.

Along the walls of a staircase, he keeps framed collections of Raphael Tuck & Sons postcards, along with news clippings and other memorabilia.

He tries his best to preserve the family’s history because he finds it fascinating, and also for the sake of his 7-year-old daughter, Madeleine0. Tuck’s mother died before Madeleine was born. And the family is so far flung that she’s been able to spend little time getting to know her Tuck side.

“This is her legacy, and this will hopefully connect her to my side of the family,” Tuck says.