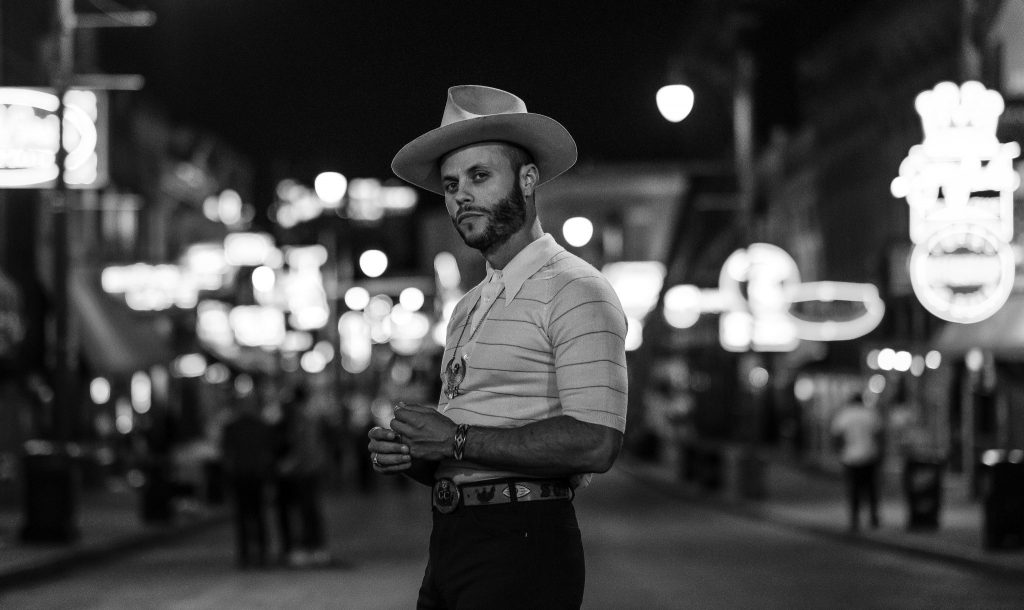

Remember Deep Ellum

Charley Crockett came up as a vagabond musician who literally lived the hobo life, hopping trains from New Orleans to New York City and performing as a street musician for years before hitting on major success in the music industry more recently.

His latest album, “Lonesome as a Shadow,” was released digitally in April. When the vinyl album dropped last year, he played a party at Spinster Records, and he headlined the Kessler Theater last summer. This past spring, he sold out the Majestic Theater in Downtown. He performs June 22 at the newly renovated Statler Ballroom.

Crockett is originally from San Benito in the Texas Rio Grande Valley, but he grew up in Dallas and New Orleans. His sound has been described as honky-tonk and rockabilly, but mostly the songs are good-ol’ 12-bar blues.

He said on the “Texas Music Scene” TV show, “People ask me what my songs are about. I say, ‘They’re about two or three minutes.’ ”

“You have one song. There’s just a lot of different ways to sing it.”

But then he told the Rolling Stone earlier this year that his perspective is from the struggle to escape poverty.

“That’s my whole message. It’s the only thing I sing about in any of my songs. That’s all anybody’s doing, really,” Crockett told the magazine. “You have one song. There’s just a lot of different ways to sing it.”

What is your connection to Oak Cliff?

I’ve played so many places in Oak Cliff. My first gig playing in a theater anywhere in the country, I was opening at the Kessler Theater. Jeff Liles [the Kessler’s artistic director] had me opening for The Weight and then he had me open for Joe Ely. I played block parties there. Some of the guys in my band are from Oak Cliff. It’s a big part of my Dallas come-up I guess.

Thank goodness for the Kessler.

It’s my favorite room in Dallas. People come to the Kessler because they know it’s going to be a good time no matter who’s playing. When you can cultivate that in a community, it’s an incredible achievement. I’ve been able to get myself off the ground through the Kessler. Jeff Liles is one of those people who saw me from the jump and was giving me the best advice I could’ve gotten. He said, “You’ve got to stop playing in all those bars for free if you’re going to come to my theater and sell tickets.” He was the first person to ever tell me that. I’d never heard that before. He was a really great, honest voice of guidance for me when I wasn’t getting it anywhere else. I’m really grateful to him for that because the rest of the scene was really tough.

There are so many great musicians from Dallas, but the music scene here is not the best in the world.

The culture that creates the artists is great here. But there’s the culture and there’s like, a scene. Dallas/Fort Worth has a very deep cultural heritage. The wellspring of talent is really unique and, in a lot of ways, unmatched. That doesn’t necessarily line up with a scene. It ties into the heritage of Dallas and why Deep Ellum was such a culturally important place for music. The amount of artists that shaped American music who played in Deep Ellum is really vast. The only thing that I would criticize Dallas on is … it’s strange to me that it can have such a rich musical heritage and there seems to be such a lack of awareness of that by the movers of the city themselves. That hasn’t ever seemed to be a problem for Memphis or New Orleans or even Austin. I mean, Austin has made itself the “live music capital of the world,” but all of the most important artists who made that possible were coming up in Dallas. Yet Dallas itself doesn’t really have that. It just continues to blow my mind. I can name 30 blues players who could arguably be the most important people in the history of American music who played on the streets of Dallas. There’s no plaques for any of them almost except for Blind Lemon Jefferson, and there’s like one plaque for him.

We don’t appreciate our own musical heritage.

Look at what happened in Oak Cliff. The money they raised to put up a [memorial for Stevie Ray Vaughan], none of it came from the city. It all came from private donations. I can’t understand how Clarksdale, Mississippi, the poorest state in America, has information and signage all through, not just Clarksdale, but all through the Delta honoring all these important artists. And they can get that together in the poorest state in the Union. And we don’t have that in Dallas/Fort Worth. For me that’s a shocking thing.

It’s a missed opportunity.

It makes business sense even. Even if the people we’re talking about are blind or insensitive to the black contribution to American music coming out of Dallas … black and white. Bob Wills and all those guys. I don’t understand why we’ve got to watch Deep Ellum turn into condos and boutique restaurants, and there’s tons of money for that. But there doesn’t seem to be anything coming from the state or the city of Dallas to make it a globally important place for audiences around the world to travel to hear the blues and Texas music history. That’s what brings people to New Orleans. That’s what brings people to Beale Street [in Memphis]. That’s my only bone to pick when it comes to what Dallas is as a scene.

Is Dallas’ musical heritage still relevant?

You talk to people who say, “That music was 100 years ago. We don’t care about that now. It’s not important.” I’ve heard that said many times. There’s a straight line from Lightning Hopkins and Bessie Smith and Lead Belly and Mance Lipscomb and T-Bone Walker … there’s a straight line from those people playing music in those neighborhoods to all the modern hip-hop that’s coming out of those neighborhoods today. It would benefit Dallas greatly to educate people walking through Deep Ellum and Oak Cliff to say, “Here’s where Ray Charles lived in the ’50s. Here’s where Stevie Ray Vaughan grew up and changed Texas blues. Here’s where Robert Johnson recorded and eventually would change the history of American music. Here’s where T-Bone Walker played barefoot in a family band on Commerce Street. Here’s where Henry ‘Ragtime Texas’ Thomas played, on this corner.” Look at the money pouring out into a lot of these business ventures in Oak Cliff. I just don’t understand why Austin can get that together, and it doesn’t have the heritage that Dallas does. But Dallas has endless amounts of money. The rich people who move that city can stroke a check and change everything. I don’t know. The more attention that comes to me, I’m going to put a spotlight on that. It’s one of the most important blues cities in the world, and the nature of this city is such that it doesn’t even recognize or acknowledge its own heritage.

You have a really good point. And I think that shows you really care about Dallas.

Dallas should not be best known for people visiting the Sixth Floor Museum where Kennedy got killed and the Dallas Cowboys. It should be known for its insanely amazing musical heritage. It’s just a choice that the city and the community make. They’re always trying to figure out how to improve tourism in Dallas. You don’t improve it by taking its most culturally rich neighborhood and gentrifying it. Because what is that going to be based on in a few years? What’s the draw? What’s the international draw to that if it’s not the musical heritage at the center of it? That’s how poor places like Tennessee have figured out how to regenerate themselves.

That would be a great thing for all the real blues musicians out there.

The real blues artists of Dallas aren’t in Deep Ellum for the most part. They’re playing at Nate’s Seafood in Addison and the Goat and the Cottage Lounge.

You’ve been touring hardcore. Who all is in your band?

Alexis Sanchez, he’s from Garland and lives in East Dallas, on guitar. Mario Valdez, he grew up in Oak Cliff, on drums. They’re Deep Ellum guys. Kullen Fox, lives down in New Braunfels, he’s my multi-instrumentalist. He plays accordion, trumpet, organ, piano, trombone, bunch of stuff. Then Collin Colby, who lives down in South Austin, is my bass player. Half the band is in Dallas, and half the band is in Austin.

You’ve been in the struggle for your art for a long time. Now you’re getting some recognition and hopefully some money. What are you looking forward to now?

It was hand-to-mouth in those days. I never knew where I was staying. That part was really difficult. But back then I didn’t have to worry about anybody else. Now I’ve got about 10 other people to think about. There’s a lot more responsibility in that way. There’s more money and more stuff on the line. But being able to have a bed in the back of the RV, and I don’t have to drive? It is difficult, but compared to standing on the side of the highway all day and doing all that hobo-ing, it’s a blessing. Every now and then a journalist will ask me if I dream about being back in that lifestyle. And the answer is “yes.” You’ve got nothing on the schedule. You’re just playing music and floating. That’s a lot easier to do when you’re a lot younger. But you asked me what my goal is now. I’m still just processing the fact that I was able to play the Majestic and sell tickets there. I’m still trying to take that in. To be able to play Majestic theaters around America in places that’ll have me, that’s my goal. If I can sell out [the equivalent of] the Majestic around the country, that would be a dream come true.