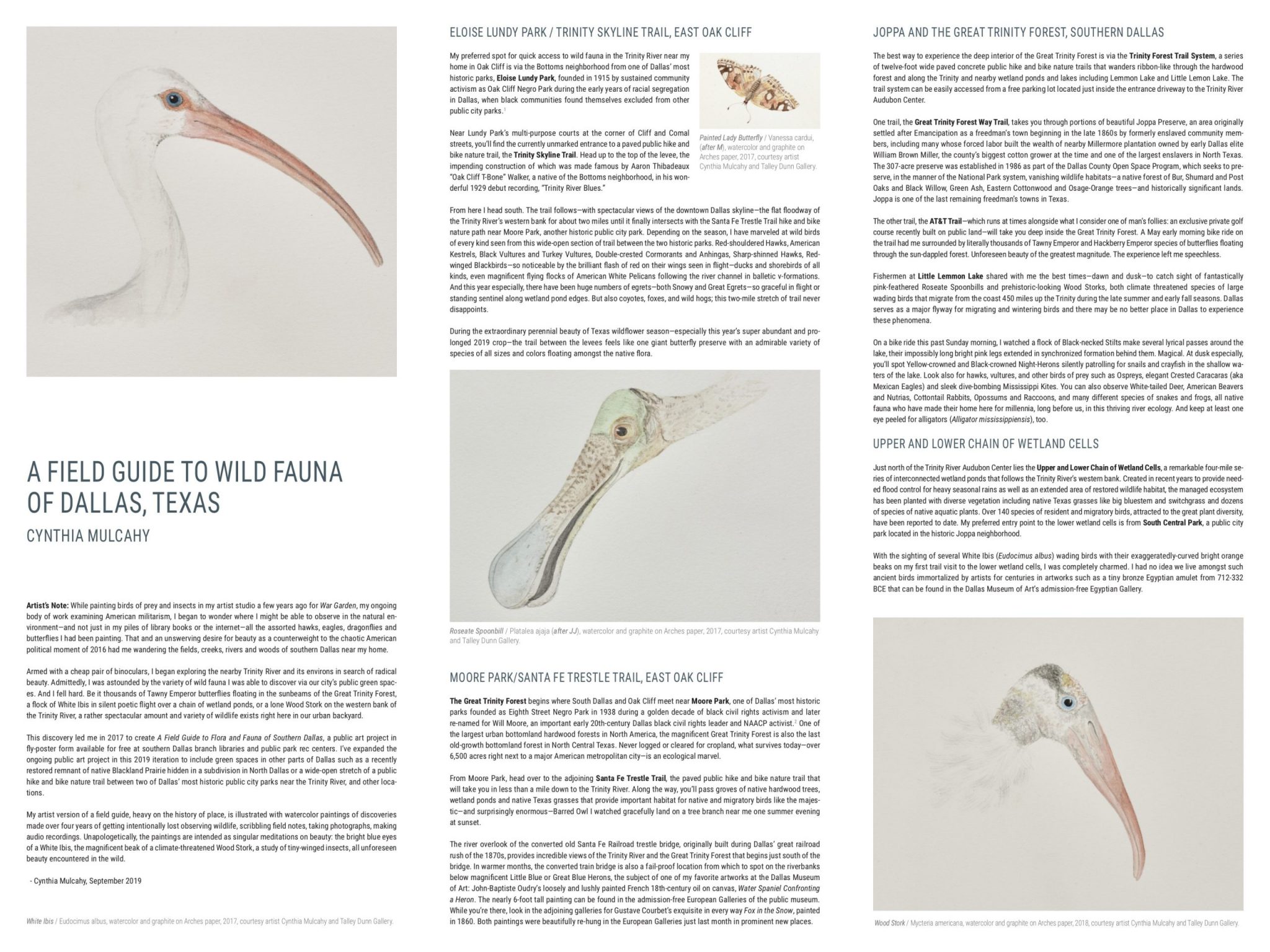

The elusive roseate spoonbill appeared to Cynthia Mulcahy during a bike ride along the Trinity River levee just this spring.

The artist had started looking for the bird several years previously as part of her two “Field Guide” series focused on the flora and fauna that’s native to Dallas.

The roseate spoonbill was the only bird she painted for the series that she hadn’t seen in real life.

“One time, I saw a pink plastic bag waving in the wind and got so excited,” she says.

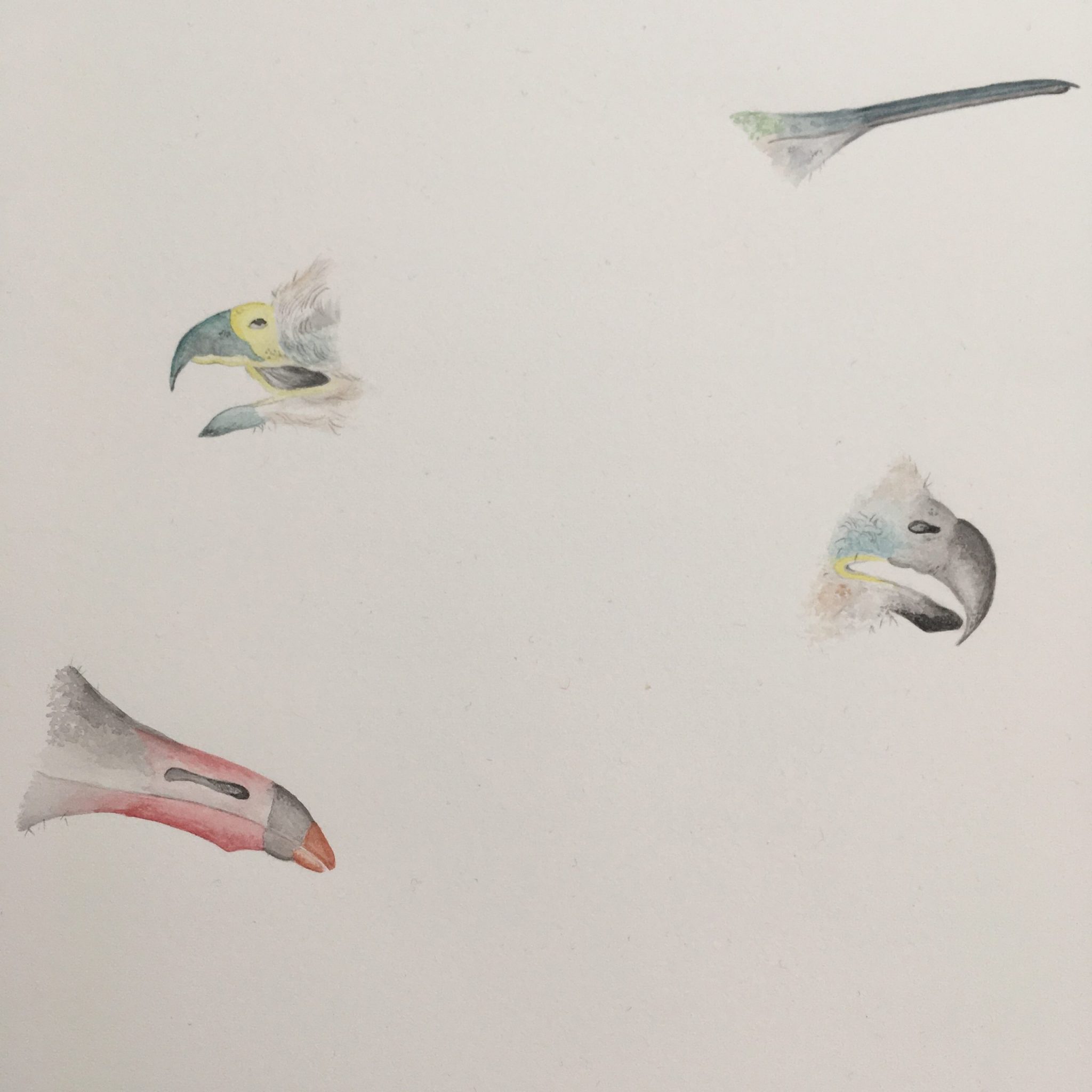

Mulcahy started painting flowers, birds and insects in the style of Victorian-era botanical drawings for her 2018 exhibition “War Garden.”

She worked on those paintings for several years, and she also took up bird watching around that time. In researching birds online and at the Dallas Public Library, she wanted a field guide that was specific to Dallas, so she made one.

“One time, I saw a pink plastic bag waving in the wind and got so excited,” she says.

Mulcahy started painting flowers, birds and insects in the style of Victorian-era botanical drawings for her 2018 exhibition “War Garden.”

She worked on those paintings for several years, and she also took up bird watching around that time. In researching birds online and at the Dallas Public Library, she wanted a field guide that was specific to Dallas, so she made one.

Her “Field Guide to the Flora and Fauna of Southern Dallas” published in 2018, and the “Field Guide of Fauna of Dallas, Texas” printed last year.

The guides are based on a series of paintings, in homage to John James Audubon’s “Birds of America,” that are compiled into fold-up posters that Mulcahy intends for practical use.

“I wanted to create something that was analog that you could take with you and have enough information to take you to certain spots,” she says. “I don’t know every bird, and I wouldn’t even pretend to. But the idea is to go out and look for yourself and then go back and research the things that you see.”

The most recent guide is printed “in an annoyingly large format for our phone-screen age,” she says. “You have to fold it out. It folds out to six parts, and you have to figure out what to read first.”

The intent is to draw us away from our phones.

With a grant from the City of Dallas Office of Arts and Culture, she printed 3,000 of them, and every branch library had 20 or 30 to give out. Mulcahy visited 28 branch libraries when the “Field Guide of Fauna of Dallas, Texas” came out.

“I consider it part of the process, and I got to know the city better,” she says. “When you’re doing a public art project in an unusual format, it was helpful for me to go introduce myself to the librarians and explain it.”

While there are hikers and guides who go deep into the Great Trinity Forest, Mulcahy prefers to stay on the trails. And the guides are meant for that level of outdoor exploration.

“My interest was, ‘How do I create a guide that the average resident of Dallas could use?’” she says.

She was previously unaware of how many large wading birds can be seen in Dallas. And she thinks it’s important to pay attention because the United States government has been rolling back the Endangered Species Act and the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, which makes it illegal to hunt, capture, kill or sell migratory birds, since the 1970s.

She would like to see signage along the Trinity River trails explaining what wildlife can be seen.

The field guide is also Mulcahy’s tribute to the majesty of migratory wading birds. Dozens of species can be seen at the Trinity River in the spring, summer and fall.

“It’s amazing what you can see here,” she says. “Anybody can do it. You don’t have to be an expert on anything.”