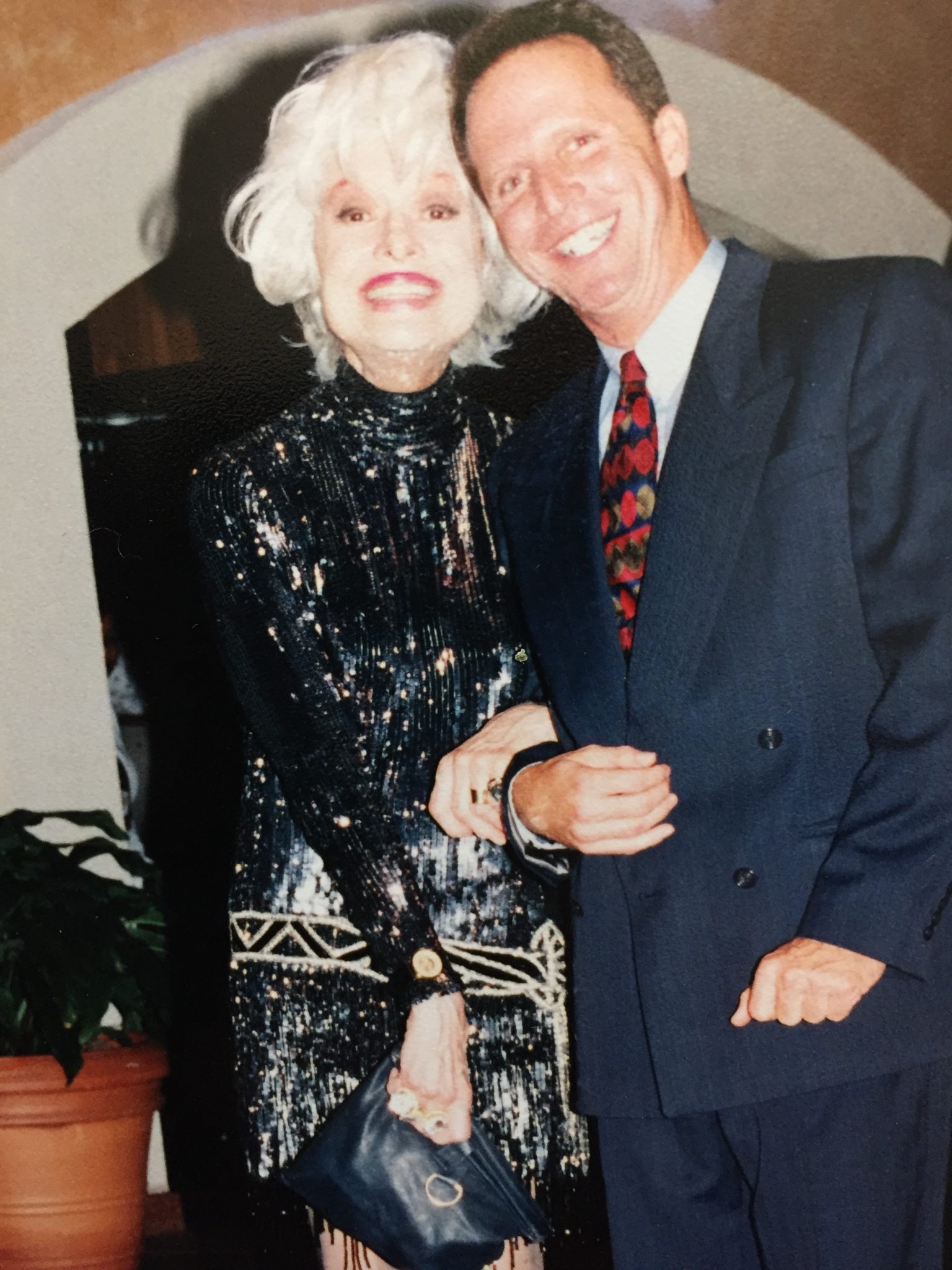

Portrait by Kathy Tran

Larry Weinstein remembers Jack Ruby coming over to his parents’ house for brunch.

“He would teach my brother and I as kids to stand on our heads,” Weinstein says. “I have memories of being joyful and playful and jolly with Jack Ruby.”

Weinstein’s dad, Abe, was friendly with Ruby then, he says, but the relationship later soured.

The two nightclub owners were neighbors in Downtown Dallas. Ruby, who in 1963 would murder JFK assassin Lee Harvey Oswald, ran a strip joint, the Carousel Lounge. And on the other side of a parking lot, across the street from the Adolphus Hotel, was Abe’s Colony Club, which also had strippers but was classier.

“Because it was tableclothed, and there was dancing, an orchestra, an emcee, a vocalist. And then later on, there would be burlesque,” Weinstein says.

His dad ran the Colony Club continuously for 35 years, from 1937-1972, which Abe believed was a Dallas record, and it probably still is. By comparison, the Lizard Lounge, the Deep Ellum club that closed in 2020, made it 28 years.

Abe’s previous venture was a “dime a dance place,” the Triangle Club, where men could pay to dance with ladies who wore evening gowns. But the city shut it down with an ordinance against “vulgar” entertainment. Abe then went into business with Pappy Dolsen, who once owned Pappy’s Showland on West Commerce but bought him out after six years.

His early success with the Colony Club came from booking what he called “Harlem acts,” performers such as Lena Horne, Louis Armstrong, Count Basie and Lionel Hampton. During World War II, “business was so fantastic,” he told the Dallas Morning News when his club was closing in 1972. “We had to hire policemen to keep people out, we were so crowded.”

The place became legendary everywhere for its strippers, including Juanita Dale Slusher, who Abe is said to have named Candy Barr. That’s when she was working for his brother Barney’s club, Theater Lounge.

Abe Weinstein also had three sisters. He was born in London and was raised in Deep Ellum, in the second story above his father’s used tie and clothing store.

But he never drank in his life. He never smoked, and he never dated a stripper or anyone who worked for him. He ran his club “like a shoe store,” he told the newspaper in ’72. He focused on the bottom line, not the glamour.

“Mom was 19, from Omaha, and she went to the Adolphus Hotel and was at a party and met my dad, who was 43,” Larry Weinstein says. “It was love at first sight, as my mother would say. Neither of them had been married before.”

Abe and Virginia had four sons: Mark, Steven, Larry and his twin brother, Garry. The twins were the youngest, born in 1953.

The Weinstein boys grew up in Preston Hollow, near Royal and Azalea, and they had a live-in housekeeper. Larry and Garry drove a ’66 Mustang to Hillcrest High School. Their dad often worked in his office at the club during the day and came home for dinner and family time before returning, “because he didn’t believe in a manager,” Weinstein says.

In 1968, Virginia Weinstein, known as Ginny, died of lymphoma at age 38.

“We didn’t have time to grieve, because dad was that way,” Weinstein says. “Dad’s sister and her husband moved in.”

Weinstein says his mother grew up Christian and never converted to Judaism, but she considered herself Jewish after marrying Abe and was a member of Temple Emanu-El. She was also a member of the international service organization B’nai B’rith, which named a chapter for her.

The Mighty 1190

“All I ever wanted to be was a disc jockey,” Larry Weinstein says.

So he went to what is now the University of North Texas, where he worked at the campus radio station and got a degree in radio, television and film.

His dad was friends with the owner of radio station KLIF, which was the only 50,000-watt radio station in the United States. KLIF hired 19-year-old Weinstein to work night shifts on weekends.

“I was the youngest, idiot disc jockey, working midnight to 6 two nights a week,” he says.

When the regular overnight DJ was fired, Weinstein moved into his slot.

“I worked seven nights a week, I bet, for six months,” he says. “That’s how much I loved it. I wouldn’t even take a night off because I loved it, KLIF, the mighty 1190.”

This was around 1974, and owner Gordon McClendon got calls from listeners who said they “didn’t like hearing a Jew on the radio,” so he asked Weinstein to change his name. Abe didn’t like that idea and had a talk with McClendon about it, but in the end, he did change it to Larry Winston.

KFLIF once had a billboard that was a sendup of an old Winston cigarettes ad, “Winston sounds good, like radio should,” depicting a speaker with smoke coming out.

After a few years in radio in Dallas and El Paso, Weinstein went to work at the bygone Dallas office of the 20th Century Fox Film Corp. as an assistant to the regional director of publicity.

Back then, Dallas had film premieres with big stars in attendance.

He once picked up Richard Chamberlain at Love Field Airport, and Chamberlain, who was still in the closet at the time, tried to pick him up.

He also drove Burt Reynolds for a movie called W.W. and the Dixie Dance Kings.

But “the worst” was Cybil Shepherd, he says. He remembers that she had 13 pieces of luggage and two limos — one for her and one for her luggage. She was promoting the Peter Bogdonavich musical At Long Last Love, which turned out to be an epic flop.

Weinstein says he forgot some of Cybil’s luggage. She complained to 20th Century Fox, and he was fired.

He got back into radio for a while, and his two older brothers opened a club in Austin called Mother Earth, where he worked a little.

From there he was hired to manage a comedy club in Houston, the Laff Stop, where he booked Ellen Degeneres, Bob Saget, Jenny Jones and Marsha Warfield.

“I then got the best job ever in my life,” he says.

General manager of Magic Island, a private magic supper club, which started in California but had a location in Houston for two years.

It had several dining rooms of varying sizes and rooms for close-up magic and larger theaters.

A lot of big stars have been obsessed with magic. Weinstein hosted Muhammad Ali, Johnny Carson and the guys from ZZ Top, including Dallas’ own Dusty Hill, who became a friend of Weinstein.

“They always came in coat and tie,” he says of the rock band. “They were so sweet.”

Weinstein later managed the 600-seat Improv theater in Chicago, and he moved to Santa Monica to open another Improv.

After six months there, Weinstein was fed up with egos and drunks in the comedy business.

“I never drank, my whole life,” he says.

A friend who was a talent scout at Star Search got him an interview with a producer and host Ed McMahon, and he was hired to warm up the taped show’s live audience.

For the next five years, he gigged as the warm-up guy for classic ’80s sit-coms: Full House, Golden Girls, Who’s the Boss, and more than he can name.

It was day-to-day work with no contracts, but it paid well.

“I kept getting those jobs not because I was so funny but because I always left when the show was over, and I never bothered any of the celebrities,” he says. “I never bothered any of the producers, because I didn’t care about being on camera. All I wanted was my $1,800 a night and the joy of doing it.”

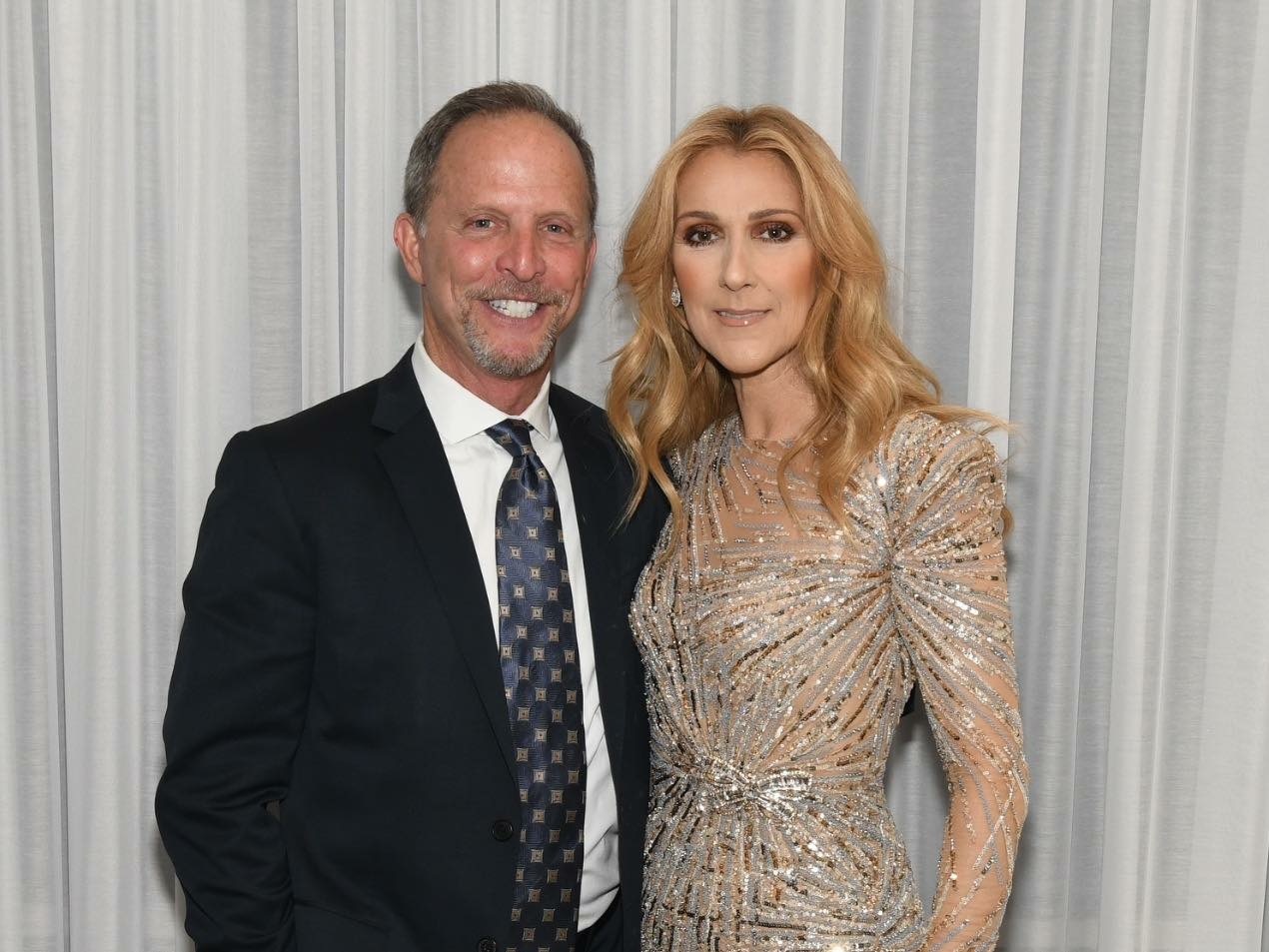

Weinstein, who now lives in Oak Cliff, returned to Dallas in the early ’90s, and he was hired as director of marketing for Harrah’s Casinos. Then Caesars Palace recruited him, and he entertained high-rollers on trips to Las Vegas for 23 years.

Caesars laid him off after the pandemic, and instead of retiring, he went to work for Wynn Resorts about a year ago, and he is the national director of casino marketing.

Abe Weinstein kept saying he wanted to live to the year 2000, and he died at age 92 on Jan. 3, 2000. He’d retired at 62 and traveled the world on cruises with his girlfriend, who he’d met in elementary school and reconnected with at 70.

Weinstein says Ruby threatened his dad with a gun the day John F. Kennedy died because Abe had opened the Colony Club that night, and Ruby was offended.

A 7-foot bouncer named Big Tex threw Ruby out, and Weinstein says his dad later regretted opening that night, but he’d thought acting normal was the right thing to do at the time.

“He ran such an ethical business,” Weinstein says. “He was always so dedicated to his family and giving us the best education and all that.”