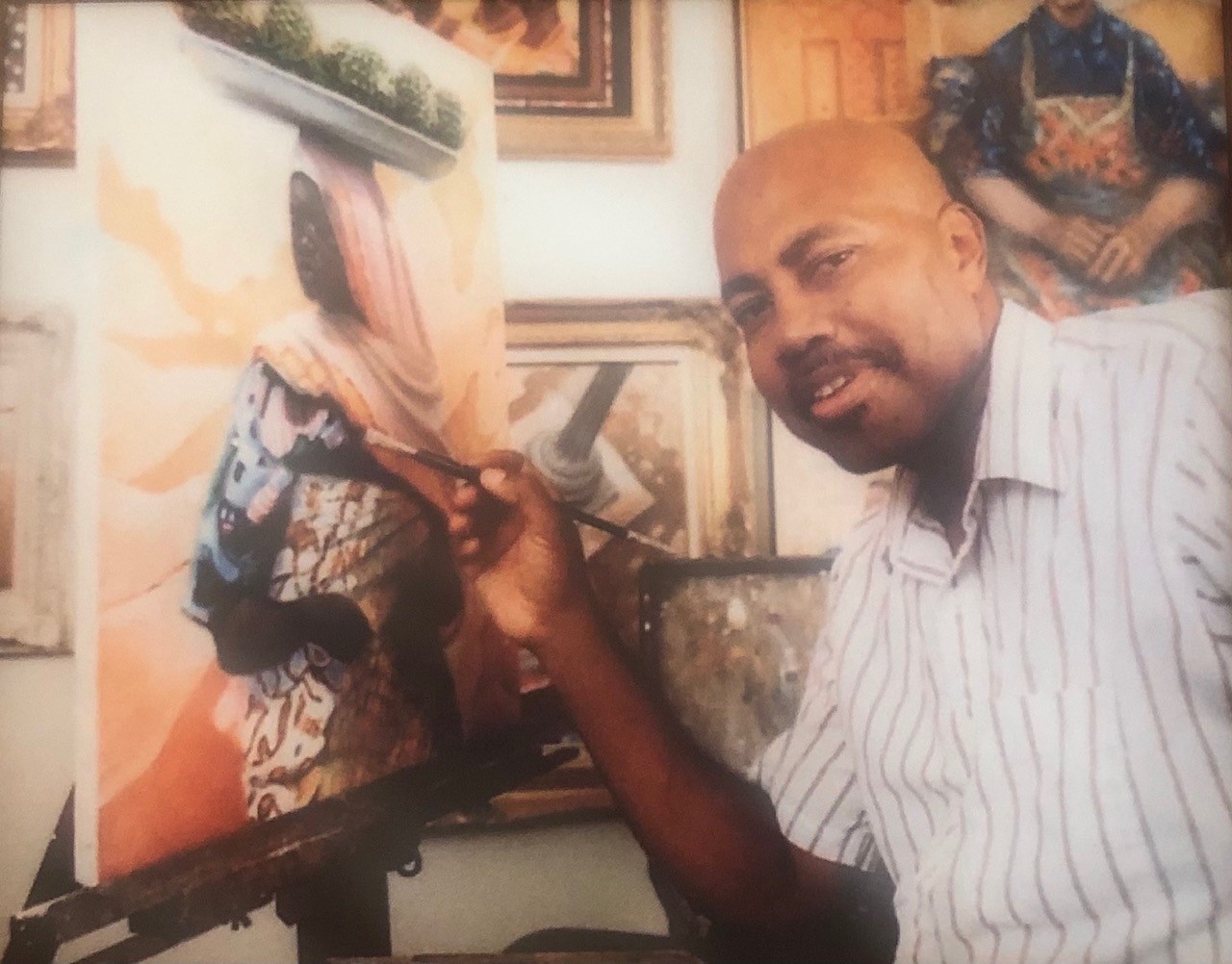

Portrait by Yuvie Styles

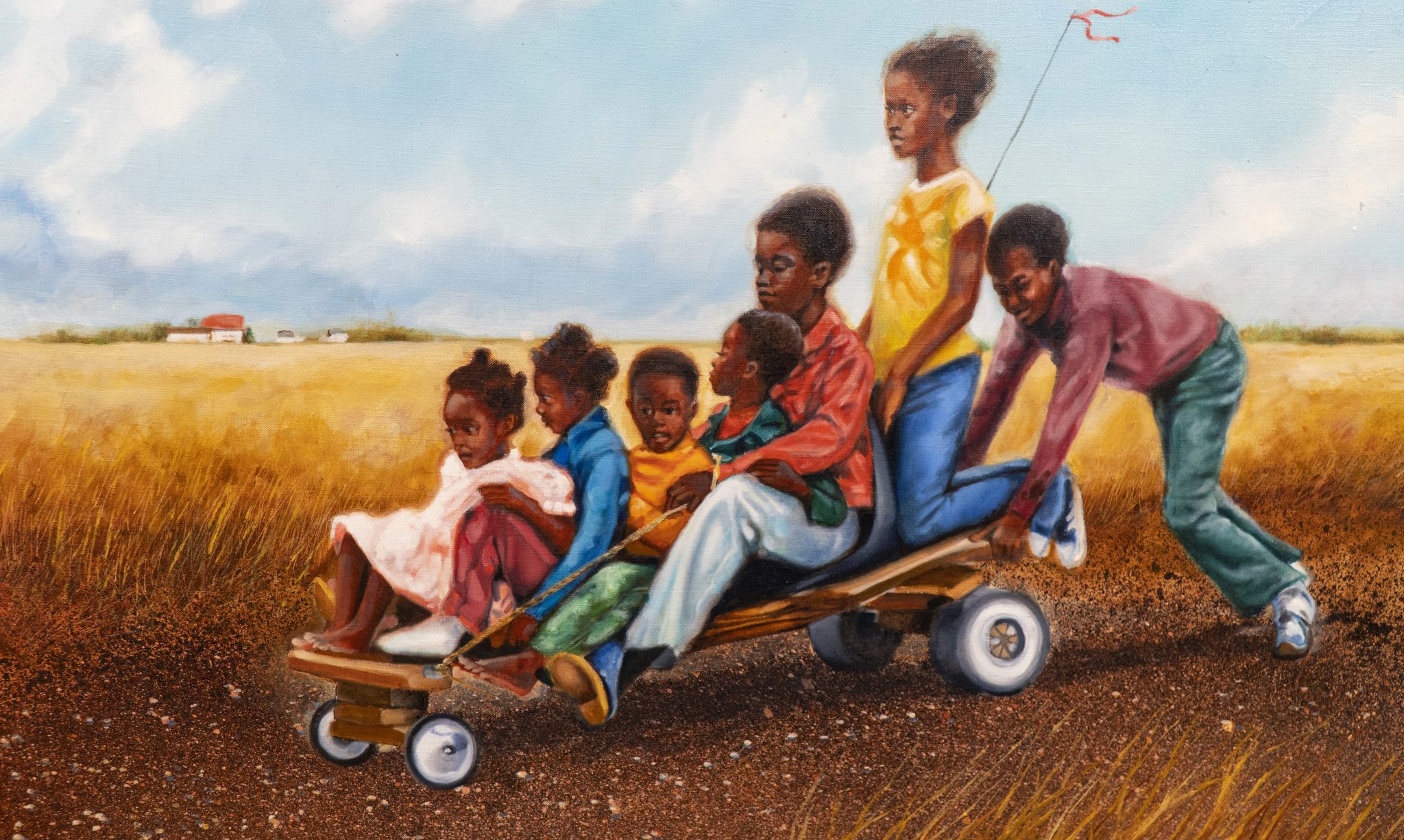

Classroom posters and textbooks didn’t depict Black people when Arthello Beck Jr. was growing up in Dallas.

His children’s schoolbooks didn’t show Black kids either.

That’s why the self-taught artist from Oak Cliff began painting Black families in ordinary situations in the 1970s.

“We didn’t have portrayals of ourselves unless it was negative,” Beck’s widow, Mae Beck, said at a recent gallery talk.

An exhibit called HUMANIZATION: The Artistic Eye of Arthello Beck Jr. at the African American Museum of Dallas recently showcased 35 paintings, including many of those “ordinary” pictures, along with rural baptism scenes, one abstract work from 1960 that’s in the museum’s permanent collection, a richly symbolic self-portrait titled “Lost Identity” and paintings of the bald cypress trees at Caddo Lake, which he produced at the end of his life.

Artist Jennifer Monet Cowley curated the exhibit, and she designed a sculpture in Beck’s honor that is expected to be dedicated at Twin Falls Park this summer.

The sculpture is based on a photograph Cowley took of her friend, the Dallas-based artist Riley Holloway, with his wife, Kelsie, and their kids, Riley and Bailey. It is of a mom and dad sitting back-to-back.

“It’s like, ‘I got your back,’” Cowley says.

The father is reading a book with his son, who’s in his lap holding a beach ball. The mother is doing the hair of her daughter, who is doing her doll’s hair. Behind them is a marsh tree, symbolizing the ones that fascinated Beck.

Cowley visited Caddo Lake twice last year.

“I wanted to see what Arthello saw and what was drawing him to that lake,” she says. “And when I got there, I immediately saw it. I saw the magic that lake has.”

Beck’s best friend, art photographer Carl Sidle, says they used to “chase the light” through the Texas Hill Country, East Texas and all the way to Louisiana and Mississippi, from morning until dusk.

The classes Beck took at Lincoln High School were his only formal art education. He was otherwise self-taught at the central Dallas Public Library.

“I used to spend hours in the library, but I never read a book,” he once said. “I may have missed a lot, but I only read the pictures.”

Mae Beck first saw her future husband at Lincoln High School, when she was a freshman and he was a senior, already known as an artist. She never spoke to him then.

They connected years later, on the campus that is now Paul Quinn College.

In the 1960s, he was painting scenes related to the civil rights movement, “and he felt the pain of the struggle,” Mae Beck says.

She told him to start painting happy things, and that’s how they came upon the idea to depict ordinary life. He was criticized for “painting Black,” she says. Some of his most famous paintings are religious, depicting Jesus and other biblical figures as Black, part of the liberation theology that influenced him.

“He wanted a gallery when I met him,” Mae Beck says.

She also wanted a gallery early in their marriage as her husband filled their apartment with paintings and often invited people over to see them.

“It wasn’t where I could feel comfortable after work,” she says. “Two or three people at a time would come in to look at his art.”

Around 1969, they rented a green shotgun house on First Avenue near Fair Park, which became a gathering place for artists, poets and musicians. The gallery moved to Ledbetter and then Saner at Ramsey before they purchased the two-story building on South Beckley that is still the Arthello Beck Jr. Studio.

The gallery was open 5-9 p.m. Monday-Friday, because Beck worked a full-time job, and he was there all day on Saturdays and half days on Sundays.

Mae Beck opened a child care center out of their adjacent home in 1978. Many of her husband’s “ordinary-life” paintings are based on photographs he took of children enrolled there.

“He was a gentle giant” is a common thing people say about Arthello Beck Jr.

Beck was 6-foot-4 and an engaging conversationalist who knew everyone in the neighborhood, his friends say.

He died at age 63 in 2004.

About the sculpture

Jennifer Monet Cowley is also from Oak Cliff, and she got to know Beck in the ’90s, when she was an assistant to the artist Frank Frazier, after graduating from the University of Texas at Dallas.

The idea that Arthello and Mae had each other’s backs inspired her. “Quality Time” is among her favorite of Beck’s paintings. It shows a father reading to his kids while a mother helps her son with homework.

The scene reminds her of her own family, she says. And it was painted in 1996, the year the oldest of her three kids was conceived.

Cowley, 54, was curator of the African American Museum for several years, and she’s also curated shows at 500x Gallery. Her own art consists of abstract paintings and textile pieces, and she’s represented exclusively by Daisha Board Gallery, on Sylvan near West Commerce. She also paints on clothing, and one of her pieces went down the runway at New York Fashion Week in February 2021 for Dallas-based designer Venny Etienne. Her painted clothes can be found at Indigo 1745 in the Bishop Arts District.

The idea for the sculpture at Twin Falls Park came to her in a dream.

“It woke me up out of my sleep,” she says.

She and her husband had just moved to Richardson, and everything was still in boxes, so she sketched the idea onto the back of an envelope. That became the basis for the conceptual drawing that the City of Dallas Office of Arts and Culture ultimately approved.

She says she’s happy to be part of making Arthello Beck Jr.’s name better known in Dallas.

“He was a genuinely nice guy,” she says. “He was a tall, soft-spoken man. Just like his best friend, Carl. He’s quiet, but when he has something to say, you’d better listen, because he truly has something profound to say.”