LOW_DSC_4336

Photography by Julia Cartwright.

LOW_DSC_4387

Photography by Julia Cartwright.

LOW_DSC_4368

Photography by Julia Cartwright.

LOW_DSC_4359

Photography by Julia Cartwright.

LOW_DSC_4411

Photography by Julia Cartwright.

LOW_DSC_4311

LOW_DSC_4309

Photography by Julia Cartwright.

LOW_DSC_4282

Photography by Julia Cartwright.

LOW_DSC_4266

Photography by Julia Cartwright.

LOW_DSC_4264

Photography by Julia Cartwright.

LOW_DSC_4251

Photography by Julia Cartwright.

LOW_DSC_4235

Photography by Julia Cartwright.

LOW_DSC_4212

Photography by Julia Cartwright.

Pull a thread on the Creative Arts Center of Dallas, and it unravels a history of local fine art in our city dating back to the turn of the 20th century and the Monet of Texas, Frank Reaugh.

Octavio Medellín started what would become the Creative Arts Center in 1966 at El Sibíl, Frank Reaugh’s home and studio near Lake Cliff Park.

“He started the school at the urging of Reaugh’s “disciples”,” says Diana Pollak, the center’s executive director.

“They were fans of his, like a fan club that kept the studio going after Reaugh’s death in 1945,” Pollak says.

For years, Medellín taught at the Dallas Museum of Art, when it was at Fair Park, which made him a great candidate to start the school.

Medellín died in 1999, and the Dallas Museum of Art is showing a retrospective of his art through February. It took about two-and-a-half years to put the show together.

The Creative Arts Center he founded, now located near White Rock Lake, still operates on the same educational foundation on which Medellín built it Pollak says.

“We abide by his teaching methods here,” she says. “We continue his philosophy of providing a nurturing space for students to learn.”

There’s no in-your-face curriculum, and students are encouraged to experiment and explore their creativity.

The center is celebrating 56 years with a newly renovated building and a planned expansion, just as its executive director is retiring after 16 years at the helm.

Play in the clay

Demand for classes at the Creative Arts Center is higher than ever Pollak says. The center offers about 500 classes a year. More than 300 students are currently enrolled, and about a third are in pottery classes.

There are 11 pottery classes a week, each with 10 students, and they’re all full through October.

“We saw it really blow up during the pandemic,” Pollak says. “If you’ve got your hands in mud, you can’t look at your phone. There’s a desire to disengage with technology and engage with other people creating art.”

Medellín required students to make their own pottery clay, but the Creative Arts Center now buys it from Trinity Clay.

“They were fans of his, like a fan club that kept the studio going after Reaugh’s death in 1945.”

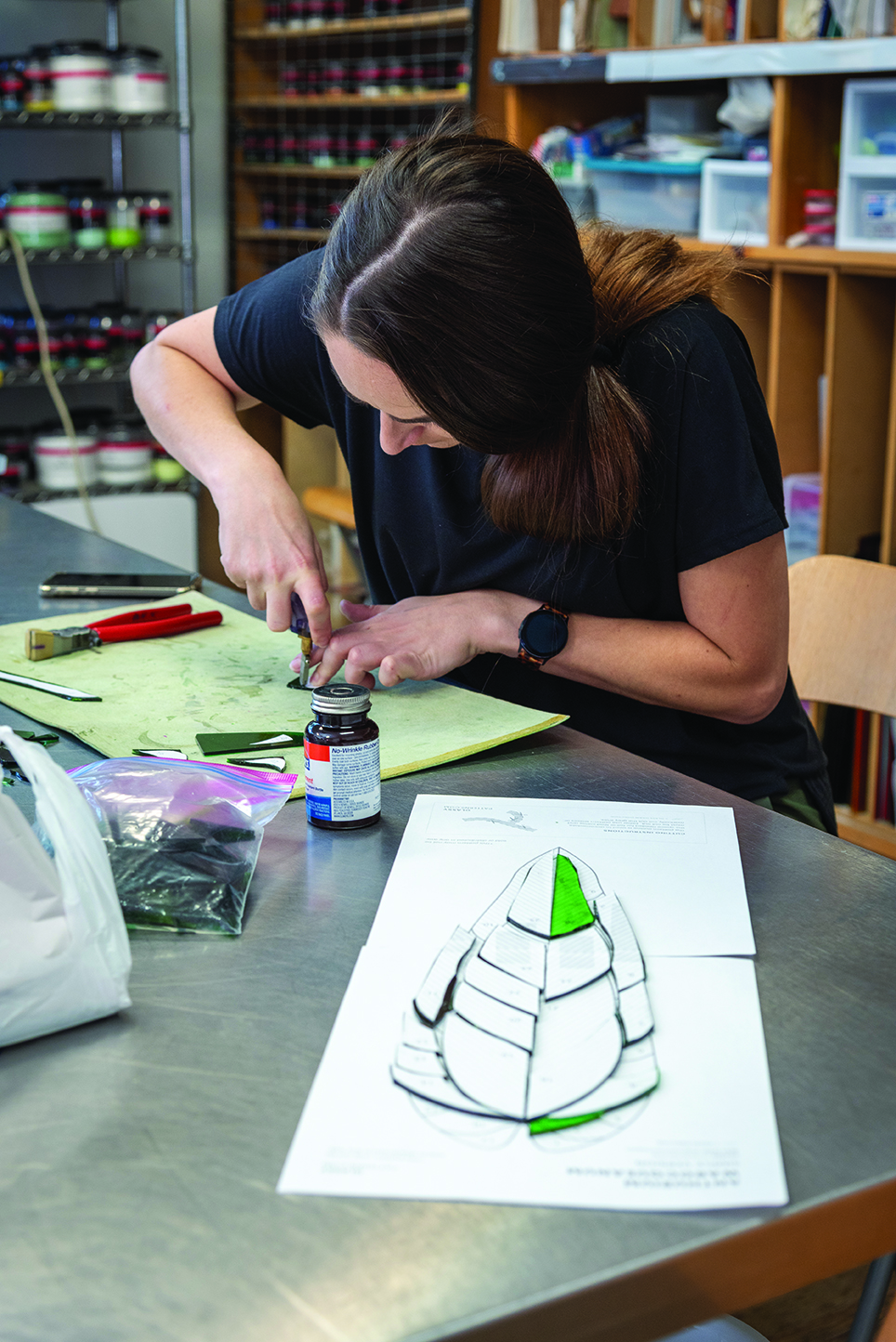

Besides pottery, there are classes in welding, painting, drawing, glass, jewelry and stone carving.

It’s easy for our neighborhood to take the center for granted, but this serious yet non-academic art school is rare. “There’s only one other [stone department] in Texas that’s comparable,” Pollak says.

No other place in Texas offers the depth of instruction.

“If you want to do stone carving, you’ve got to come here,” she says.

In March 2020, the nonprofit Creative Arts Center’s board of directors had been expected to approve a feasibility study to launch a campaign to raise $5 million for an expansion. That would’ve added a second building to the 2-acre campus, doubled its capacity for classes and added gallery space for art exhibitions.

“Then the pandemic hit, and everything came to a halt,” Pollock says. “We’re now in a holding pattern.”

Renovations of the offices and gallery, totaling about $500,000, were recently completed. That included updating Americans with Disabilities Act compliance to the original building, the old Works Progress Administration-built Bayles Elementary.

The center has been a stop on the White Rock Lake Artists Studio Tour for decades, showing one piece from every artist on the tour. The new gallery means the center can expand on that and offer more shows to new artists and those who have been affiliated in the past.

Since the center is a nonprofit, it receives grants to provide free classes and camps to the community. Camp Metal Head, for example, teaches welding and jewelry to underserved kids. Run with the Pack offers creative classes to older adults.

The legacy of Octavio Medellín

The Dallas Museum of Art’s Octavio Medellín: Spirit and Form is the first museum retrospective of his work.

Medellín “was obsessed with materials,” Pollak says. He dabbled in many media, but he was best known as a sculptor.

“Medellín’s grand legacy can be attributed to both his incredible talent and his enormous influence in our community as a mentor to so many,” says Agustín Arteaga, the museum’s Eugene McDermott director. “We hope this exhibition cements his place among the most important artists working in Texas in the 20th century.”

Dallas-based artists Edith Baker and Marty Ray were among Medellín’s students. Artists influenced by Medellín have returned to teach at the Creative Arts Center.

“We like to say that he influenced generations of Dallas artists,” Pollak says.

The indigenous art of Mexico was Medellín’s main influence.

He was born in San Luis Potosí, Mexico, the same year as Frida Kahlo, 1907. His family immigrated to San Antonio in the wake of the Mexican Civil War in 1920. He studied at the Art Institute of Chicago but left to travel in Mexico.

“He journeyed to Mexico City, where he explored Mexican Modernism, encountering important artists such as José Clemente Orozco and Carlos Mérida, but also traveled on foot through the rural countryside of the Gulf Coast,” according to the Dallas Museum of Art.

Mexico is where his point of view blossomed.

The retrospective includes 30 sculptures Medellín produced from 1926 to 1995.

Pollak says she’s seen the retrospective six times. “I see something new every time I go.”

Medellín also produced a ton of public art in San Antonio and Dallas. The museum also put together a driving tour of his public art in Dallas, as part of the retrospective.

The Creative Arts Center is on the map, along with St. Bernard of Clairvaux Catholic Church, where Medellín created the altar wall and stations of the cross. His work can also be seen at the Latino Cultural Center in Deep Ellum, Southern Methodist University, Calvary Hill Cemetery, Temple Emanu-El and Love Field Airport.

Learn more about Octavio Medellín at medellin.dma.org.