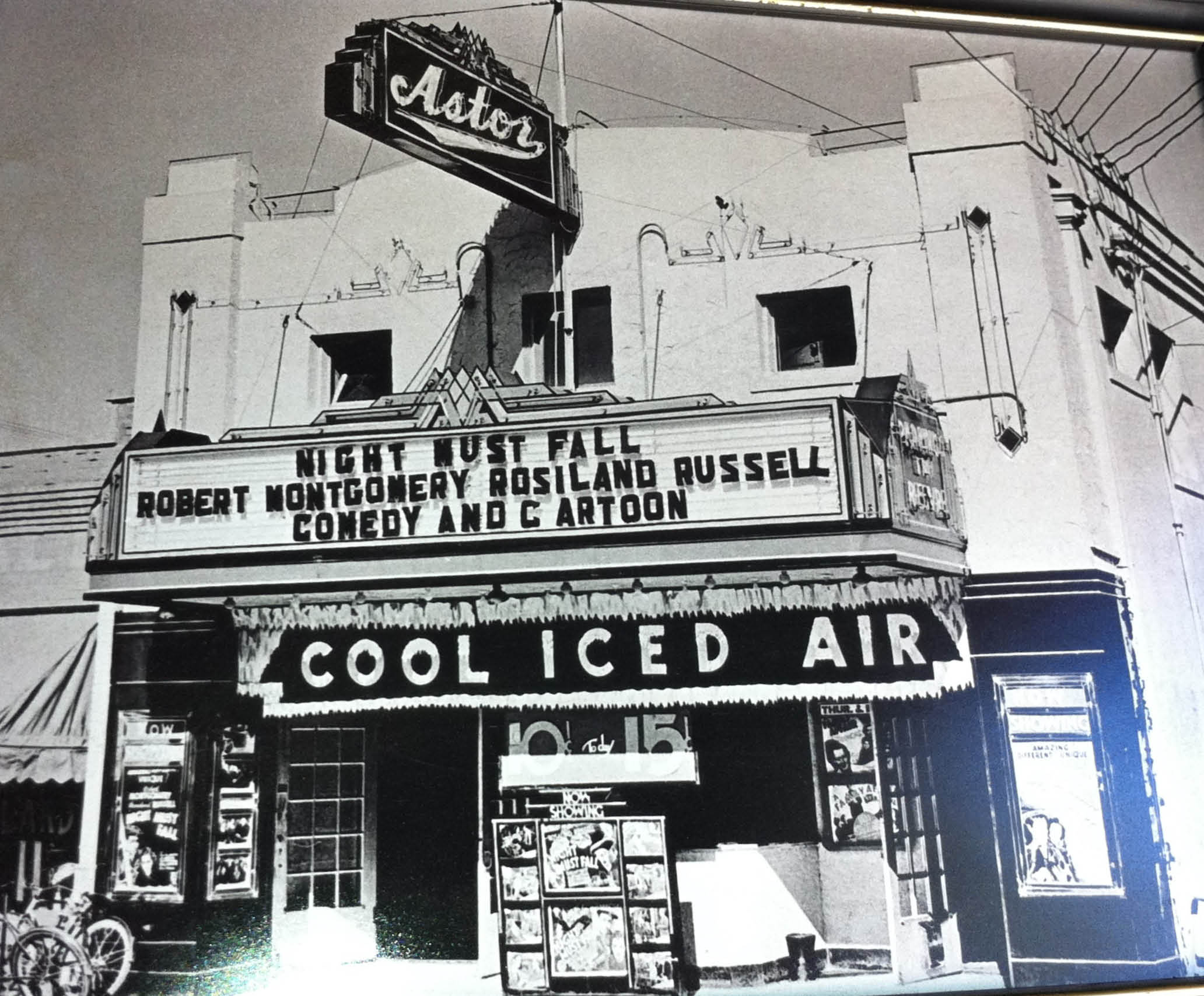

Martin Weiss was an arts patron, and he paid for the Rialto Theater at 412 N. Bishop out of his own pocket. It later was renamed Astor: Courtesy of Bob Johnston.

Just in case any of you have wondered about the “Weiss Building” imprint signage atop the brick facade over Hattie’s in Bishop Arts District, or about the Martin and Charlotte Weiss Building at Methodist Dallas Medical Center, or about Martin Weiss Park or Martin Weiss Elementary School, well, here’s the story.

Hungarian immigrant Martin Weiss arrived in New York City in early 1889. The 23-year-old was sent there alone by his widowed mother, who had scrimped and saved enough to pay for his passage. Inside her son’s coat, she had sewn $84.

Knowing no one, and neither reading nor speaking English, Weiss managed to secure a full-time job with a harness maker, earning a whopping $5 per week, and a part-time job serving as a guide to a blind violinist at $4 per week. After a year in NYC, Weiss decided to move to Gonzales, Texas, the home of the violinist’s sister and her family, where he lived with the family, worked for the sister’s husband, and learned to speak and write in English from the family’s daughter. Finally saving up a $125 nest egg, Weiss traveled to San Antonio, purchased some dry goods, bought a $2.90 train ticket and headed for what he believed to be greener pastures.

With only 60 cents left in his pocket when he arrived in San Marcos, Weiss used a drum and dinner bell he had purchased to attract customers, and stood on the town square with his wares. By mid-afternoon he had sold everything. Wiring the San Antonio wholesaler for more goods, Weiss repeated the pattern over and over until he acquired $2,000 worth of merchandise and had $1,350 in the bank.

Weiss did well. He married, became involved in civic activities, invested in a Beaumont oil business — and then proceeded to go broke.

In 1911 the Weisses arrived in Dallas, where they settled in a $10-per-month rent house in Oak Cliff. Weiss managed to borrow enough money from a local bank to purchase a bankrupt millenary business in downtown Dallas. He also began investing in real estate.

Eventually, he made a fortune.

Even though during World War I the United States was fighting Hungary, the country of Weiss’s birth, Weiss mortgaged his home to purchase Liberty Bonds.

His generosity to the struggling seemed to have no boundaries. At Christmastime he donated toys and clothing to orphanages of all denominations. He let people live in his house rent-free until they were able to repay him. He awarded gold watches to the top students at Oak Cliff/Adamson High School and greatly supported the programs and growth of what was then called Methodist Hospital, a facility that sat only a few hundred yards away from his home on Bishop Avenue. He also donated money to the Dallas Park System.

[quote align=”left” color=”#000000″]Always striving to benefit his community, Weiss personally paid for the construction of a stage at what was then the Rialto Theater at 410 Bishop (currently the address of Artisans Collective in the Bishop Arts District).[/quote]Always striving to benefit his community, Weiss personally paid for the construction of a stage at what was then the Rialto Theater at 410 Bishop (currently the address of Artisans Collective in the Bishop Arts District).

“To accommodate ‘prologues and entertainments,’ a stage was installed in the Rialto in 1921,” wrote Bob Johnston in a July 29, 1926, Dallas Morning News article, stating that a new theater organization was being planned under the sponsorship of the Oak Cliff-Dallas Commercial Association and the Oak Cliff Society of Fine Arts. “Use of the Rialto Theater and of rooms nearby suitable for dressing rooms and rehearsal rooms has been granted by President [Martin] Weiss, who owns them, and an orchestra, headed by S. M. Shaver, has offered its services for music at the productions.” Using the stage, the Oak Cliff Players — later the Oak Cliff Little Theater — presented its first production, opening on Dec. 6, 1926, for three performances of “Why Not?”

True to Weiss’ civic commitment, when the original cabin of early Oak Cliff settler William Henry Hord was scheduled for destruction in 1926, Weiss and his wife, Charlotte, were able to halt the plan and later donated the structure to Oak Cliff’s American Legion Post 275. In 1962, the cabin became a designated Texas Historical Landmark. Committed to helping improve Dallas and Oak Cliff until the end, Weiss also penned a 30-page booklet at 89, three years before his 1957 death, titled “Martin Weiss, Dallas Builder: his dreams of a great project, straightening and navigation of the Trinity River.”

[quote align=”right” color=”#000000″]Martin and Charlotte Weiss died childless. But their tombstone tells their story the way they wanted it told: “To Live in Hearts We Leave Behind Is Not to Die.”[/quote]Asked later about his philanthropy, Weiss explained his motivation: “I am only handing back to the people of my state what they give me. I can never repay all the United States has done for me, but I can show my gratitude, and in that I use as my guide the thought of what my mother would have me do.”

Interred in Dallas’ Emanu-el Cemetery, major Dallas philanthropists and civic leaders Martin and Charlotte Weiss died childless. But their tombstone tells their story the way they wanted it told: “To Live in Hearts We Leave Behind Is Not to Die.”

And certainly a reflection of his grateful and humble spirit, under Weiss’ name are the simple words: “Devoted and Beloved Husband.”

The world needs more Weisses.