35 homes.

That is how many residences in the Tenth Street Historic District have been torn down in the last 14 years due to a city zoning ordinance that allowed for the demolition of residential structures smaller than 3,000 square feet within a Landmark District.

The ordinance made it easier for modest homes to be declared substandard by the city, paving the path to demolition. But it wasn’t enforced evenly across the board.

Dallas’ historic Black neighborhoods, Tenth Street and Wheatley Place, did not have a single home larger than 3,000 square feet within their boundaries when the rule went into effect. Residents of those neighborhoods saw teardowns take place at a fast clip, while residents of primarily white neighborhoods did not.

Fourteen years later, the city has finally acknowledged the disproportionate effect the 3,000 square foot ordinance had on Black and brown neighborhoods.

“The default for these homes became demolition, rather than consideration for rehabilitation,” assistant city manager Majed Al-Ghafry wrote in a memo to the Dallas City Council earlier this year.

On Feb. 28, the council unanimously voted to repeal the ordinance. While the repeal is a win for preservation advocates, it is bittersweet for those who live in the neighborhoods that were crushed by the rule.

In the words of Tenth Street resident Larry Johnson: “At this point, there’s really not a lot of Tenth Street left to tear down.”

The writing on the wall

From the beginning, everyone knew that the 3,000 square foot ordinance was going to impact Black neighborhoods.

Former Dallas Mayor Tom Leppert, who was no friend to preservationists, led the charge on identifying buildings that were urban nuisances as part of a campaign to clean up Dallas. He insisted buildings be brought up to code or else face the bulldozer.

In 2009, the ordinance was beginning to work through the city process. Then-First Assistant City Attorney Chris Bowers told the Dallas Observer that the deterioration of historic district homes “primarily in Southern Dallas” was the catalyst.

He referred to Tenth Street, one of the last remaining Freedman’s Towns in the country, as the “poster child” for Dallas’ deteriorating history, and he questioned the viability of the neighborhood’s continued existence.

The ordinance passed unanimously through the Zoning Ordinance Advisory Committee in 2010 before moving on to the City Plan Commission and City Council. And each step of the way, city preservation planner Kate Singleton was sounding the alarm for the clear impact the “heinous” rule was going to have.

“I was writing memos saying ‘Please don’t do this,’” Singleton says. “Starting in like 2011, Preservation Dallas and the Landmark Commission and the neighborhood tried to get it rescinded because of all the studies about what it was doing to our low-income historic neighborhoods.”

A study by the Dallas Office of Equity and Inclusion found that demolitions in Tenth Street “at least doubled” following the implementation of the 3,000 square foot rule. It also found that the only historic districts that had homes larger than 3,000 square feet, therefore unthreatened by the ordinance, were majority-white neighborhoods such as Junius Heights, Lake Cliff, Munger Place, Swiss Avenue and Winnetka Heights.

Singleton left the city shortly after the ordinance passed, but came back as Dallas’ Chief Preservation Planner last May. When discussion about the 3,000 square foot rule began to gain traction, she felt that “finally” she could fix what she’d always resented.

She credits city council member Carolyn King Arnold, whose district includes Tenth Street, with “kicking the door open” on the ordinance’s repeal process.

But what “got the city’s attention,” according to Johnson, was a 2019 lawsuit filed by the Tenth Street Residents Association under the Fair Housing Act. It points out that in the 25 years following historic designation, 72 Tenth Street homes were demolished in total.

The lawsuit was thrown out, but it did result in the city council temporarily halting demolitions.

“That it took 14 years for people to realize that this rule disproportionately affects Black neighborhoods shows the condition of our city, of our state, and it shows the depravity of our democracy,” Johnson says. “It’s a rule that never should have been in the first place.”

An uphill battle

In the city council’s discussion of the 3,000 square foot rule, council member Jaynie Schultz applauded the repeal, stating that Tenth Street had been “abused for too long.”

Council member Arnold urged her peers to continue their support of the neighborhood in future initiatives as it continues to face “rapid gentrification.”

And council member Omar Narvaez said he was sympathetic to the history that has been lost to the Tenth Street teardowns.

“We have to protect these neighborhoods,” he said. “We as Latinos also understand, because Little Mexico is no more. It doesn’t exist.”

A century ago, the neighborhood around Pike Park was thriving and dominated by Mexican immigrants, many of whom were fleeing the Mexican Revolution. When Harry Hines Boulevard sprouted up, the road and its economic impact cleaved through the neighborhood in a way similar to I-35’s impact on Tenth Street.

What stands today are the glittery restaurants, bars and luxury living spaces that make up the Harwood District. The pink, Spanish-style apartments known as the Little Mexico Village are one of the last remnants of Little Mexico.

Next to the million-dollar high rises, they look out of place despite dating back to the 1940s.

It is stories like that of Little Mexico’s demise, as well as a history of city redlining and racism, that contribute to the distrust that still permeates many Tenth Street residents’ view of Dallas and those who run it.

James McGee is the President of Dallas Southern Progress, a community development organization focused on improving the quality of life in the Southern half of our city. While McGee is not a resident of Tenth Street, he estimates that he sent well over 100 emails in 2023 regarding the neighborhood.

McGee has been working for Tenth Street pro bono, trying to help the neighborhood identify city, state and federal funding for improvements. Since taking on the self-appointed role of neighborhood advocate, he says he has been told that the city will not engage with him because he does not reside within the district.

McGee shared over a dozen emails with the Advocate that were sent to the District 4 office in 2023 asking for engagement or conversations over Tenth Street issues. Each email went unanswered. Repeated phone calls to the District 4 office also went unanswered, McGee says.

Many of McGees emails are asking about the funds allocated in the 2017 Bond for sidewalk repairs in Tenth Street. The funds remain pending, seven years later.

And in the 2024 Bond, Tenth Street was completely left out despite Arnold telling the horseshoe that she hoped to use discretionary funds for the neighborhood.

Arnold did not respond to requests for comment from the Advocate.

In an interview with the Dallas Observer, Arnold said that she was unable to build a funding package for Tenth Street in the 2024 bond. She allocated the $5 million in discretionary funds for District 4 to the Dallas Zoo, “a neighbor of Tenth Street,” and says that a partnership between the Dallas Zoo and city Park and Recreation department could lead to zoo programming about the neighborhood.

Missing out on bond funds was especially bitter for Johnson, who dreams of rebuilding the Sunshine Elizabeth Chapel. The church dates back to 1889 and was demolished in 1999 after falling into disrepair. But when Tenth Street was in its prime, it was a “community hub.”

Where the church once stood is now empty land, still owned by the church’s small-but-mighty congregation. They moved to a church south of Tenth Street after the demolition, but “like the idea” of returning to the historic space and rebuilding as a community center.

“Given that social services will come out of this building, that makes it a prime candidate for city funding,” Johnson says. “Not only will it provide services for the community, but it will also be a heritage tourist site. People will come from far and wide.”

Johnson says he has petitioned for bond funds that could be used for the church’s rebuilding multiple times over the years, but has repeatedly been told no.

“It’s frustrating, when you have an elected official who doesn’t understand,” Johnson says. “But it’s especially frustrating when that official looks like us. It would be an easier pill to swallow if the council woman was Hispanic or White or Asian, but she’s Black. And she still doesn’t care.”

Preserving the Freedman’s town

Frustrated with the city, McGee has started looking elsewhere for support.

He has coordinated a partnership between the Tenth Street Historic District and the Texas A&M University landscape architecture department; students visited Tenth Street earlier this spring and are spending the semester problem solving solutions for the neighborhood.

Four college courses are being offered under the partnership, covering historic preservation, design and architecture. A syllabus for the program outlines dates of site visits, virtual Q&A’s with Tenth Street residents and meetings with “key stakeholders” like McGee.

When Johnson met with the students, he was struck by their interest in affordable housing and walkable communities, which Tenth Street models.

“That’s kind of added wood to the fire,” he says. “It’s not just about preservation, but it’s also about building for the future.”

As conversations about affordable housing continue to dominate Dallas city politics, Singleton finds herself “infuriated” when looking to Tenth Street as the perfect example of a missed opportunity. Of the 35 homes demolished due to the 3,000 square foot rule, half could have been rehabilitated, she believes.

“You just let a bunch of (affordable housing) be torn down,” Singleton says. “Those houses (that were lost), a family could have lived there. This could have been a little stepping stone for them to buy a little house, rehab it and build up equity.”

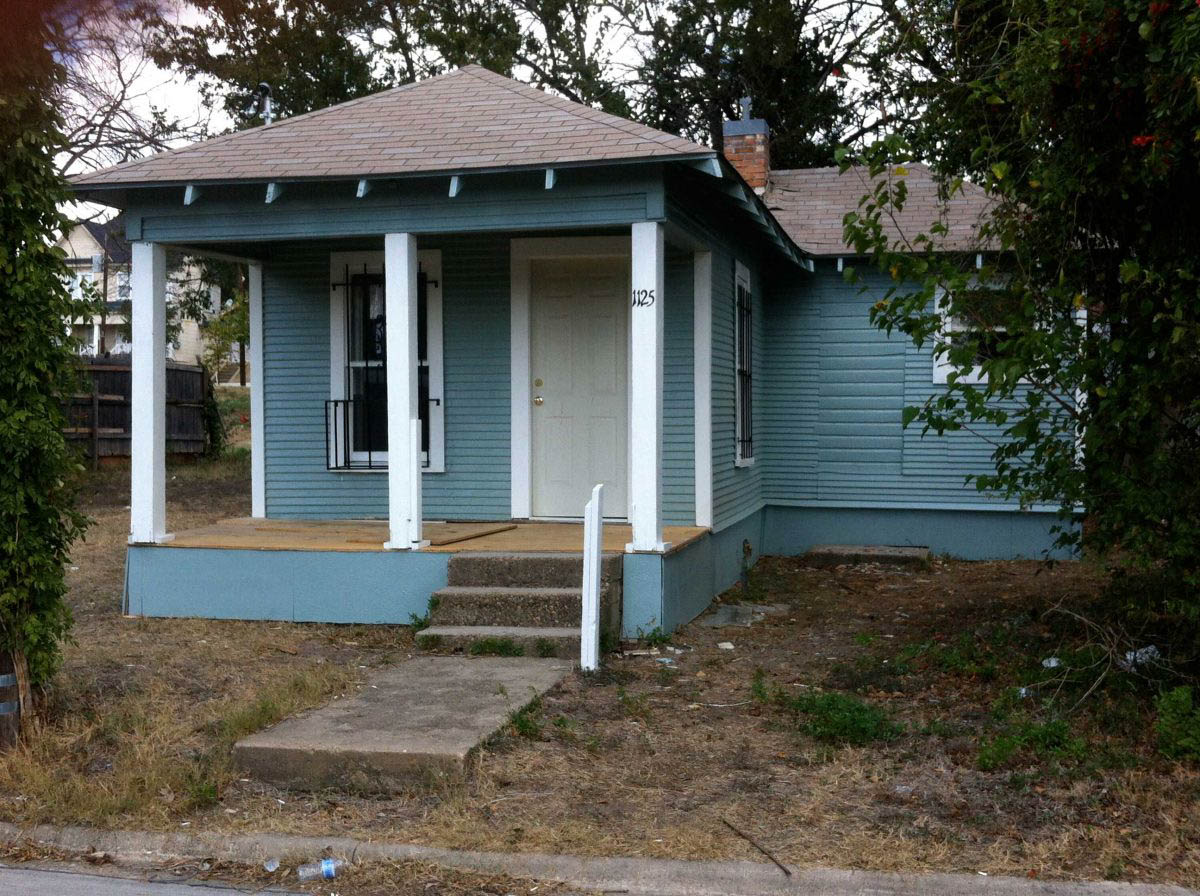

District 4 Landmark Commissioner Robert Swan also warns of the unique home types that could be lost if Tenth Street continues to decline. He says shotgun houses with pitched roofs are a rare home type that make up the district, but other rare houses are less easily described because their style is specific to Tenth Street.

He says a typology based on direct observations of Tenth Street’s design has yet to formally take place. With 72 homes demolished since the historic district was designated, it’s uncertain what has been lost.

While city funding for basic repairs, much less historical signage, may seem like a pipe dream to McGee, Johnson is taking things into his own hands. He plans to install a sign in his front yard honoring the history of his home, which was built sometime between 1895 and 1905, and the people who lived there.

“From a historical standpoint, a lot of (preservation) is about building design,” McGee says. “But Tenth Street is a little different. It’s about the people who lived in those houses.”