Hoppy days

Demand for local craft beer led to the first Brew Riot home-brew festival in Oak Cliff in 2009.

It was held in the parking lot behind Eno’s.

“Lots of people will tell you they were there, but I can tell you, they were not,” says Greg Leftwich of Four Corners Brewing Co.

At the time, McKinney-based Franconia Brewing Co. was virtually the only craft brewer in North Texas, and Eno’s was one of the few places that offered a variety of craft beers. But there were a lot of serious home brewers, and drinkers wanted better beer.

In other words, the market was wide open. That little home-brew festival in Bishop Arts led to several start-up breweries, including Four Corners and Noble Rey Brewing Co.

Now, fewer than 10 years on, the craft-beer scene in Dallas is robust. There are about 50 breweries in North Texas.

When Local Urban Craft Kitchen opened at Trinity Groves a few years ago, the restaurant offered nearly every craft beer available in North Texas. They still exclusively sell beer that is brewed within 75 miles of the restaurant, but they’ve since given up filling growlers in favor of obtaining a license to sell hard liquor in order to stay relevant in the market; they now offer cocktails made with Texas made spirits and local beer.

But L.U.C.K. co-owner Jeff Dietzman, whose family is originally from New Mexico, says he thinks there’s room for more.

“They have 27 breweries in Albuquerque. Albuquerque is the size of Arlington. There are two breweries in Arlington, and they’re both a year old,” he says. “As dense as the population is here, if the support was there the way it is in Portland or Albuquerque, there could be many more breweries.”

Oak Cliff Brewing Co. is betting on it. The brewery in Tyler Station is expected to start rolling out kegs this year. Here is their story, along with those of two other breweries that got their start in Oak Cliff.

Oak Cliff Brewing Co.

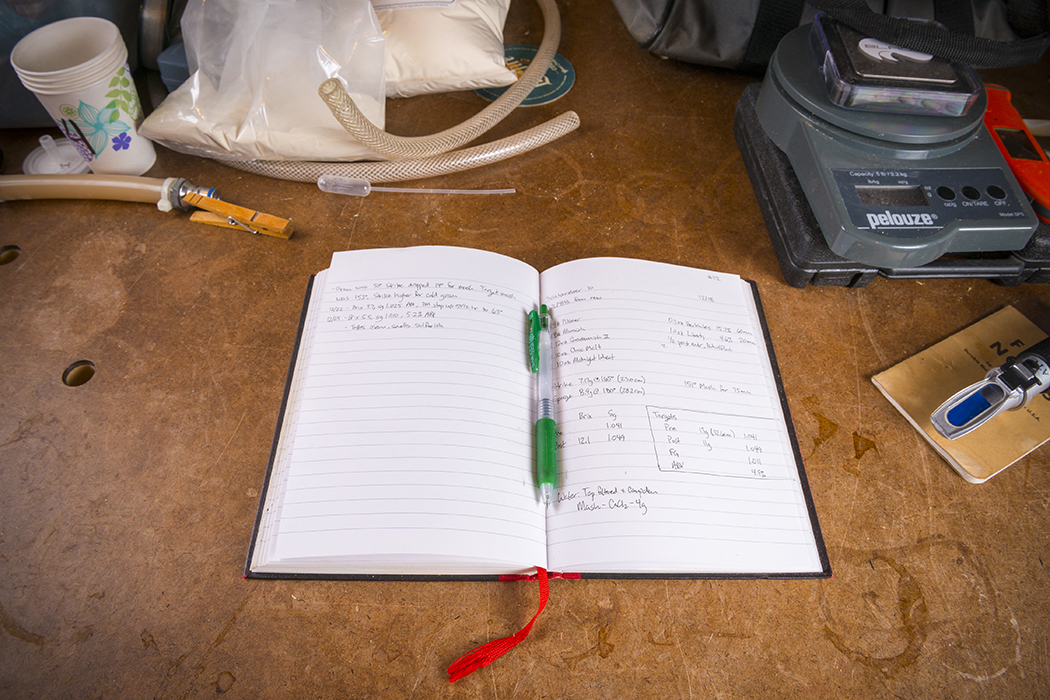

Oak Cliff Brewing Co. was still working out of owner Joel Denton’s garage this winter, but the brewery and taproom could open at Tyler Station as soon as this spring. (Photos by Danny Fulgencio)

Brewing beer appeals to Joel Denton, a 46-year-old software engineer, on many levels.

It involves community, chemistry, creativity and engineering.

Speaking of which, Denton’s efforts to open Oak Cliff Brewing Co. at Tyler Station have involved feats of engineering.

He and his partners are building a 900-gallon capacity brewery on the second-story of a 100-year-old industrial building.

It took 13 tons of structural steel to shore up the cavernous room that will hold the brewhouse and its 10-ton tanks.

“We knew coming in that it would be very challenging to put a brewery here,” Denton says.

But there aren’t many industrial sites in Oak Cliff, and the ones here typically lack character. Denton knew he wanted to name his beer “Oak Cliff,” so he just had to brew it here.

When it’s finished sometime this year, the brewery’s taproom will open to the DART line. And they’ll be delivering kegs of approachable beer, such as their black lager, a helles exportbier and a grapefruit gose. Denton has hired a brewmaster, and they’re also working on a lager.

Like many brewers, Denton’s story starts in the garage.

In 2007, a guy at work gave him some homebrewing equipment. He started brewing, and after a few batches, he began entering competitions and winning them.

His job at a healthcare company provides for Denton, his wife and their family. But it doesn’t satisfy his soul, he says.

“When I think of what I want to do for the next 22 years, it’s not that,” he says.

So he began making plans for a brewing company.

Denton is from Oak Cliff. His grandfather was a pastor who had a church near Kiest Park. His wife, Mei, is from that area, as are his three cousins who are partners in the brewery. Hence their tagline, “Beer with roots.”

Denton started working on the brewery in 2015, and he initially thought he’d be open in a year. It’s been a longer journey than that, but they’re hoping for a spring opening, after which they’ll be hauling and delivering kegs to their vendors themselves.

“It’s such an accomplishment just to get it open, but then there’s so much more to do,” he says.

Bishop Cider Co.

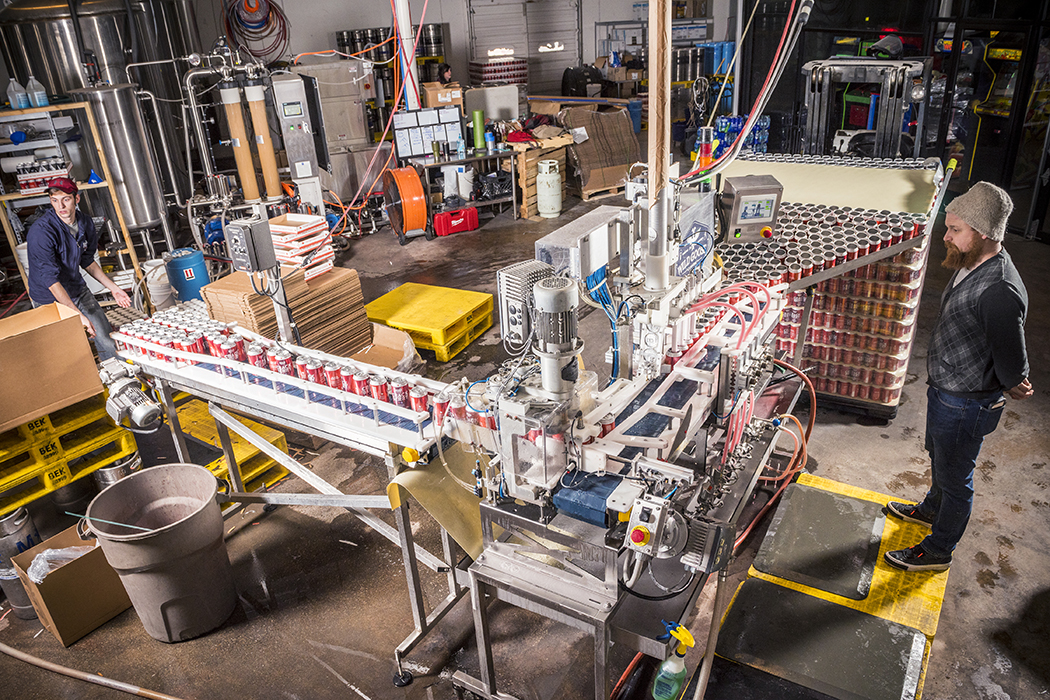

Bishop Cider Co. started with a 700-square-foot taproom in the Bishop Arts District and now brews about 20,000 gallons a month. (Photos by Danny Fulgencio)

Unlike craft beer brewers, Bishop Cider Co. has very little competition anywhere.

“We just realized that ciders on the store shelves were overly sweet, and they were all the same,” says co-owner Joel Malone, who lives in the Kidd Springs neighborhood. “There was nothing local.”

Malone, a digital marketing consultant at the time, raised a little bit of money through a crowd-funding campaign to help rent a 700-square-foot Bishop Arts storefront and brew a few kegs of cider.

It took Malone and his wife, Laura, 26 months from inception to opening, and 1,200 people showed up to their grand opening party in 2014, Malone says.

Now the cidery brews about 20,000 gallons a month from its brewery in the Design District. Their five varieties of cider are distributed in cans and kegs all over Texas through Ben E. Keith. They also operate Cidercade, which offers all-you-can-play video games for $10, plus 24 ciders on tap.

Besides having a unique product that’s well marketed, Bishop Cider puts a heavy emphasis on the personality of the business.

“We’ve grown because people have come and experienced our culture,” Malone says.

Manhattan Project Beer Co.

The Manhattan Project Brewing Co. expects to begin construction this year on its new brewery and taproom in West Dallas.

Five years to the day after Deep Ellum Brewing Co. opened the first craft brewery in Dallas, Manhattan Project Beer Co. went into production.

“Competing in this market five years after it started is challenging,” says co-founder Karl Sanford.

The project currently brews out of Bitter Sisters Brewing Co. in Addison, but they are buying a 10,000-square-foot West Dallas warehouse with plans to turn it into a brewery and add on a 1,500-square-foot taproom, plus a beer garden.

Sanford and his wife, Misty, became serious about home brewing when they decided to brew a batch for their wedding in 2011. They asked their friend Jeremy Berodt to help. The beer took six months to perfect, but it was a success. They started entering competitions, including Brew Riot, and overall, they won 27 medals.

“It was a somewhat silly hobby that we took pretty seriously, and it naturally evolved into a commercial venture,” Sanford says.

It’s no wonder. Karl Sanford is a project manager. His wife owns a digital marketing company called North of Creative. And their partner, Berodt, is an embedded software engineer.

The Sanfords cashed out of the Winnetka Heights house where they lived for 10 years and moved to an apartment on West Commerce. They’ve been busy raising the capital, about $4 million, to start their brewery; they closed on the property in January, so construction could begin soon.

Sanford says he thinks the tastes of craft beer consumers in North Texas are becoming more sophisticated, and that drinkers are being converted from basic American lagers all the time.

“Everybody’s seeing that it’s becoming competitive,” he says. “We’re facing the same challenge that any business faces.”