70- to 90-somethings share the secrets to eternal (or at least very long lasting) youth

American Industrialist Henry Ford once said, “Anyone who stops learning is old, whether at 20 or 80. Anyone who keeps learning stays young. The greatest thing in life is to keep your mind young.”

Ford touched on a secret that many Oak Cliff people have unearthed and embraced. Learning and doing create a motive for living well. These folks, some two decades past retirement age, are not ready to kick back and let the golden years quietly pass.

Africa tour guide: Emma Rodgers

Emma Rodgers drove all over Dallas looking for books to give as party favors for her 5-year-old son’s birthday party.

It took her all day to find 10 books she liked for the children.

That was 1977. Later that year, she and a colleague started up a mail-order business, selling books. A few years later, they opened Black Images Book Store in Wynnewood Shopping Center.

“We felt that if we had a need for books for ourselves and our children, then other people would have the same need,” Rodgers says.

The business flourished for 30 years, serving the neighborhood as well as Dallas ISD, for which they ordered books, and major corporate clients.

They closed Black Images in January 2007. But Rodgers, 67, keeps herself busy in retirement.

Next year, she will begin her third term on the City Plan Commission. She is a board member for the TeCo Theater, and during the summer, she teaches a class at the day camp there. She facilitates a monthly book club at Charlton Methodist hospital. She volunteers as a publicist for the annual Irma P. Hall Theater Arts Festival. And she is the founder of Romance Slam Jam, an annual literary conference that brings readers and romance writers together, now in its 17th year.

The cause that’s closest to her heart, however, is ROPP Inc., a six-year enrichment program for teenage girls. Every other year, she organizes and guides a trip for the girls to Ghana, West Africa.

Through the program, girls learn life skills such as community service and how to manage money, as well as practical skills such as cooking and sewing.

At the end of the program, they graduate with a rite of passage that is based on African traditions. It was Rodgers’s idea to bring the girls of ROPP to Ghana for the ritual.

The girls raise money themselves for the trip.

“I went to London one time, and this lady said to me, ‘I’ve never seen any black people on ‘Dallas’ ” Rodgers recalls. “There were no black people on that show, and that’s all she knew about Dallas.”

Americans have similarly misguided conceptions about Africa, she says.

“I want Americans to become familiar with the continent of Africa because on the news, all we see are the negative things about Africa — famine, mismanagement, war,” she says. “And there’s so much more to it than that.”

Old mechanics never retire: Jim Walston

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bqE6K5ffREY[/youtube]Airplanes are Jim Walston’s life.

His dad was an airplane mechanic in World War I, and Walston always knew he wanted to work with planes.

He started working on airplanes in the early ’40s, and now at 88 years old, he’s still working on them.

Walston is a member of the Vaught Retiree Club, having worked in the Vaught Aircraft Industries structures test lab for 37 years. The club currently is restoring a 1942 V-173, “The Flying Pancake.”

It was an experimental plane. The U.S. Navy wanted to build a plane that could take off and land in very short distances. And only one was made.

Walston works on the plane at the former Vaught Aircraft Industries plant, which is now owned by Triumph, twice a week.

Jim Walston retired from Vaught Aircraft Industries in 1988. Now he restores old planes. Photo by Benjamin Hager

He and other volunteers started rebuilding the plane in 2003, and they expect it to be finished by the end of this year. Once it is restored, it will go in the Frontiers of Flight Museum at Love Field.

The surface of the Flying Pancake looks like shiny metal. But the aircraft actually was built with a wooden frame, covered in canvas that is painted and sanded. The club had to rig stands for the plane as they worked on it because they can’t walk on its surface.

This plane is the most unusual the club has worked on, but they already have restored three other Vaught planes. They’re working on a reproduction of the first plane Vaught ever built, the 1917 V-E7 “Bluebird.” And they’re restoring two other vintage planes.

Walston went to airplane tech school in Fort Worth just after he graduated from High School in Italy, Texas. He went to work as a mechanic, working on Fairchild PT 19s, in Vernon. And then he joined the U.S. Army Air Forces in 1942. He served in England and France during World War II, from March ’44 until June ’45.

After the war, he attended Texas A&M University. Upon graduation, he received a job offer from Vaught. The last plane he worked on, in 1988, was Northrop Grumman’s B2 Spirit, the “Stealth Bomber.”

It was a fun career because he received a new project every five years or so, he says.

After retirement, he played more golf at Stevens Park. He also volunteers at Methodist hospitals. And he and wife Glenna have been members of Cliff Temple Baptist Church since the ’40s. But volunteering with the plane restorers has kept his mind on a life-long passion.

In Walston’s home office, there is no computer. But there is a poster of the Stealth, amid pictures of airplanes and grandkids. He pulls out an old book showing World War I airplanes.

“I always loved airplanes,” he says. “I was always looking at airplane magazines.”

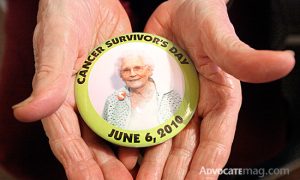

Cancer survivor devotes her life to volunteering: Jean Barrar

Jean Barrar remembers riding home from the hospital Dec. 24, 1956, thinking it would be the last Christmas she would spend with her children.

She’d had cancer surgery, a colostomy, and her odds of surviving were one in four. She thought she was going home to die.

For the next five years, she lived in constant fear of death. But on the five-year anniversary of her surgery, in 1961, she realized she was going to live.

“They said if you could survive five years, then you were cured,” she says. “I tell people I’m like a butterfly. I had a chrysalis.”

She spread her wings volunteering for the American Cancer Society, and serving cancer patients became her lifelong passion. At first she drove cancer patients to Parkland for X-ray radiotherapy. When Baylor Hospital acquired a cobalt radiation machine, she and other volunteers brought carloads of patients for treatment.

She soon realized she had a gift for working with patients. She would drive to sick people’s homes and convince them to go back to treatment.

She served on the American Cancer Society’s Texas board. And in 1982, she helped conduct a cancer prevention study. She served as a spokeswoman for the American Cancer Society and visited people in hospitals. And she has put in hundreds of volunteer hours with other charities and service organizations, including First Methodist Church, where she has been a member since 1934. She also had a career as an executive assistant at a scale company.

She remembers visiting a woman who had just received a colostomy, and she was threatening suicide.

“When she saw I lived with this hole in my side all these years, that made her see it was OK,” Barrar says.

Barrar, who is 91, lived most of her life in Oak Cliff, but she has lived in Vickery Towers retirement center in East Dallas for the past nine years. Her vision has started to fail, so she can’t drive, which prevents her from volunteering as much. But she still does as much as she can. She’s a “Caring Caller” through the Senior Source, so she calls someone who’s homebound once a week to chat. She’s a new-resident ambassador at Vickery Towers. And she still volunteers at church.

“My mother told me she wanted to wear out, not rust out,” Barrar says. “I’m minding my mother.”

35 years at the zoo: Marietta Janak

Marietta Janak is the longest-serving Dallas Zoo volunteer. Here she is at the Giants of the Savannah exhibit with Jenny the elephant in the background. Photo by Can Türkyilmaz

When Marietta Janak started volunteering at the Dallas Zoo in 1976, she worked with a possum, a chicken and a snake.

Janak, 75, and other volunteers would bring these “teaching animals” to schools, nursing homes, clubs and anywhere else they were invited, and give presentations about wildlife.

She was even allowed to take animals home with her, and her family took a particular shine to the boa constrictor. She tells a story about putting the snake in bed between her husband and herself one cold winter night.

“My daughter always says she never knew what she was going to find in the bathtub when she got home from school,” Janak says.

Janak later handled a screech owl and a ferret in her years as a volunteer teacher for the zoo. Later, she worked in the now-defunct nursery, feeding and playing with baby gorillas and orangutans, among other baby animals. And for years, she helped gather scientific research at the zoo.

Times have changed.

The zoo now has professional animal researchers on staff. There is no more nursery. Animals born in the zoo stay with their mothers. And animals only leave the zoo under the watchful eye of a professional nowadays.

Janak’s job has changed too.

Most days, she can be found in the Jake L. Hamon Gorilla Conservation Research Center, where volunteers man an information desk and answer questions about the zoo’s gorillas, Juba and B’Wenzi. When she’s not there, she’s at the Giants of the Savanna, talking about elephants and giraffes.

“The size of the zoo has doubled,” she says. “But I’m glad they’ve kept a lot of the historical features. The building in Zoo North, which is Bug U now, used to be the entry to the zoo, and it was made by the WPA.”

Nowadays, people are better informed about wildlife because of all the nature shows on TV, she says. Many times, kids want to tell the zoo volunteers everything they know. There are humorous moments. About one in every thousand visitors to Giants of the Savanna sees the ostrich egg on display and gasps, “Oh! Is that an elephant egg?”

It takes a sensitive person to answer that question with a straight face: “No. Elephants are mammals …”

The zoo staff members’ attitude toward Janak and the other volunteers has changed as well.

She says they once were treated like “bored housewives,” but now zoo employees are always supportive and grateful of volunteers.

“The people I’ve met, and the friends I’ve made,” she says. “We all had one common love, and that’s for the zoo and the animals.”