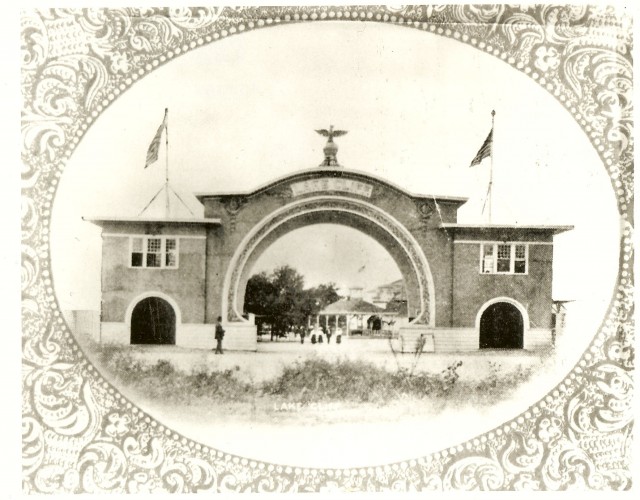

This 2,500-seat Casino theater once was part of Lake Cliff amusement park. When the park closed, developer Charles Mangold relocated the building to Fifth and Crawford where it become the James P. Simpson Studio, which burned down in 1929. Photo courtesy of Joe Whitney

Oak Cliff’s original name, Hord’s Ridge, honored William Henry Hord, one of Dallas’ earliest settlers. His 640 acres, across the river from John Neely Bryan’s cabin — and set roughly where the Dallas Zoo is now — rested in front of a “ridge” of sorts. The name made sense … then.

Six years earlier, Hord had traveled from his home in Tennessee to join Gen. Thomas J. Rusk in East Texas to assist with Native American issues. Known as a kind and courteous man, Hord was elected as Dallas County’s first county clerk in 1846 and later served as a brigadier general of Texas militia troops during the Civil War — before becoming one of the signers of a resolution to restore all confederate states. Hord, a founder and vice president of the Dallas Historical Association and the leader of the Dallas County Conservative Party, earned the title “judge” when he later became a longtime Dallas County justice of the peace.

[quote align=”right” color=”#000000″]The developer understood that naming the area for the stately green oaks on the cliff was more appealing and melodious than the earlier tag. He also developed a park that included a large pavilion where stage shows and summer operas were presented. Later the home of the city’s menagerie, the Marsalis Park Zoo existed until 1985, when the name was changed during a remodeling project.[/quote]When his wife, Mary Hord, became determined to educate the couple’s only daughter at home, she found herself running a boarding school for girls. Attracting young ladies from as far away as White Rock Creek on the north to Ellis County on the south, the schoolmistress was forced to begin charging 12 1/2 cents per day to cover both tuition and board.

Henry Hord became a founder and trustee of the Oak Cliff Cemetery, where he and Mary are interred. The family’s original log cabin was rescued from demolition by Martin and Charlotte Weiss in 1926 and donated to local Veterans of Foreign Wars Post 275 in 1947. Of note: John M. Crockett, Mary Hord’s brother, served as the second mayor of Dallas. Also of note: The Hords’ daughter married W. A. Crawford, assumedly the reason for the naming of Crawford Street on the east side of Lake Cliff Park.

In 1886, developer Thomas L. Marsalis bought land that included most of the Hord farm, where he opened his “Oak Cliff” subdivision — Marsalis’ new and more appropriate name for the town. The developer understood that naming the area for the stately green oaks on the cliff was more appealing and melodious than the earlier tag. He also developed a park that included a large pavilion where stage shows and summer operas were presented. Later the home of the city’s menagerie, the Marsalis Park Zoo existed until 1985, when the name was changed during a remodeling project.

In 1906, Charles A. Mangold (along with furniture czar John F. Zang) developed Lake Cliff Park, which opened first as “The Llewellyn Club.” The 44-acre playground boasted a roller coaster, water rides, three theaters, a dance pavilion, a Japanese Village and a roller rink.

A testament to all these men, both the zoo/park and Lake Cliff Park remain today.

As shared in an earlier column, residential developers helped pay for the operation of rail lines to and from their subdivisions in a brilliant effort to bring potential homebuyers out to view the lots and new houses being promoted. One of the first in the region was that of the aforementioned T. L. Marsalis, who built the Dallas and Oak Cliff Railway in the 1880s for $250,000 and touted it as “the first elevated railway in the South.” Actually, the term “elevated” was a bit of a stretch. The only elevated section of the line was the trestle bridge across the Trinity River. The two termini (the eastern terminus at Record and Commerce and the western at Jefferson and Beckley — for a number of years the end of the line) all had ground-level approaches and extensions.

The railway was described as a steam-powered rapid transit railway that had canopy-covered stations every two blocks up Jefferson Boulevard, serviced by wooden coaches that Marsalis bought from the New York system — adding to the illusion that his system was “elevated,” like the one in New York City. According to quotes and information from Charles C. Walsh in the book “Dallas Yesterday” by Charles Acheson, the only charge to ride the shuttle railway was 5 cents when passengers traveled to or from Dallas. All residents of Marsalis’s sub-division were allotted annual passes, so according to Walsh, “All Oak Cliff youngsters had a ball in riding the trains without charge in Oak Cliff.” Walsh stated that the rail system had four locomotives that “were of unending interest to Oak Cliff youngsters of the day.” All were fueled by coal hauled in from West Texas. (Yes, Texas. Texas is a significant coal-producing state. Who knew?)

In his old age, William Henry Hord moved in with his daughter and son-in-law, who lived in what was called Flanders Heights off present-day Fort Worth Avenue. Business partners T. L. Marsalis and John S. Armstrong made their fortunes in the wholesale grocery world before entering the real estate development business. After forming the Dallas Land and Loan Co. to develop Oak Cliff, the partners had a disagreement and Armstrong pulled out. But he moved north and developed … Highland Park! Marsalis filed for bankruptcy in 1893 reportedly moved to New York, where he lived out his life in relative obscurity and then died in poverty, passing away in Patterson, New Jersey. But he is well remembered thanks to the familiar North Oak Cliff street and elementary school, both bearing his name.

Although these early Oak Cliff founding fathers all left their marks on our community, I’m sure they wouldn’t recognize the area today, especially if any of them were standing along Jefferson Boulevard waiting for one of the steam railway trains to the Lake Cliff Amusement Park. But I think they’d be amazed. Perhaps lunch at Trinity Groves followed by a trip over the Margaret Hunt Hill Bridge and a tour of Kessler/Stevens. Yep! I think the guys would be impressed.