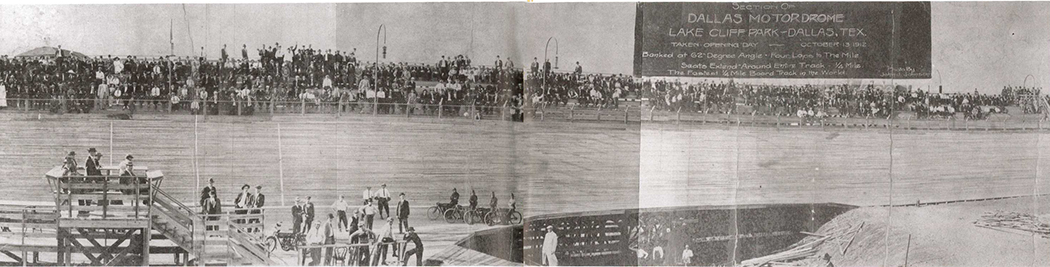

A panorama from Oct. 13, 1912 shows part of the quarter-mile motordrome at Lake Cliff Park. Note the steeply banked walls and rows of spectators. (Photo courtesy of the Texas/Dallas History and archives division, Dallas Public Library)

Oak Cliff’s short-lived motorcycle racing arena

Professional baseball is a big part of Oak Cliff’s history. And we recently uncovered that the first pro hockey games in Dallas were played here as well.

Oak Cliff was home to early 20th century bicycle racing as well as the renowned Big D Cycles motorcycle shop and racing team.

For a very short while, there also were death-defying motordrome races in Oak Cliff.

A motordrome was built at Lake Cliff Park in 1912. This was back when Lake Cliff was an amusement park — it also had a “shoot the chutes” water ride, a café, a theater and a roller rink.

Motordromes, which gained wide popularity in 1910, were board tracks — oval racing tracks composed of wooden planks and extending a fracton of a mile. The one in Oak Cliff was a quarter of a mile. The tracks were banked so that when racers got up to high speeds, they could go near-horizontal along the walls.

“The Texas Cyclone,” Eddie Hasha, whose dramatic death contributed to the demise of motorcycle track racing. (Photo courtesy of the Texas/Dallas History and archives division, Dallas Public Library)

These were spectacularly dangerous races that drew crowds numbering in the thousands. According to newspaper accounts from the time, the Lake Cliff motordrome was built to seat 6,000, about the same capacity as the Will Rogers Coliseum.

Unfortunately, the motordrome at Lake Cliff was built at about the worst time possible for the sport.

James S. Arthur of St. Louis built the motordrome with several partners for $2,000 in advance of the State Fair of Texas. Arthur arrived in Dallas near the end of September 1912.

A few weeks earlier, motorcycle board-track racing suffered a tragedy that would put an end to the sport’s popularity and begin its rapid decline.

A rising star of the track was a racer from Waco named Eddie Hasha, called “The Texas Cyclone.” Hasha began his career in November 1911, racing on an 8-valve Indian motorcycle. He set a record for the mile, averaging 95 miles per hour. And he beat all of the sport’s established stars for a first-place finish at the Los Angeles motordrome, the arena at the heart of board-track racing.

On Sept. 8, 1912, Hasha raced against world-record holder Ray Seymour at the Newark Motordrome in New Jersey.

A horrendous crash suffered during that race would shock the world with its gory and tragic aftermath.

This account of it is paraphrased from motorcycle racing historian David L. Morrill:

Hasha came around a turn upwards of 90 miles per hour and hit the rail. His bike rode the rail for some 100 feet, killing a boy who had been leaning over to watch the race.

Hasha’s body flew into the stands, killing him instantly. The crash killed four other spectators, three of them children.

The motorcycle then dropped back into the arena and killed another racer.

Pandemonium ensued. Many spectators were seriously injured in a stampede to flee the arena.

In all, seven were dead, including five spectators. Paramedics were called from all over the city.

The disaster made the front page of the New York Times, and the 2-month-old Newark motordrome never reopened.

Two weeks later, as New York newspapers were dubbing short-track motorcycle racing arenas “murderdromes,” the guy from St. Louis started building one here.

We know the Lake Cliff motordrome opened that fall and held races at late as November 1912, when neighbors complained that they’d held races on a Sunday, violating blue laws.

There is no clear record of whatever happened to the Oak Cliff motordrome, but it’s not hard to imagine. The outdoor tracks weren’t built to last anyway, and after about three years of use, they became difficult to maintain.

Some of them became auto- or bike-racing tracks. The last two — in Coney Island and the Bronx — disappeared before 1950.