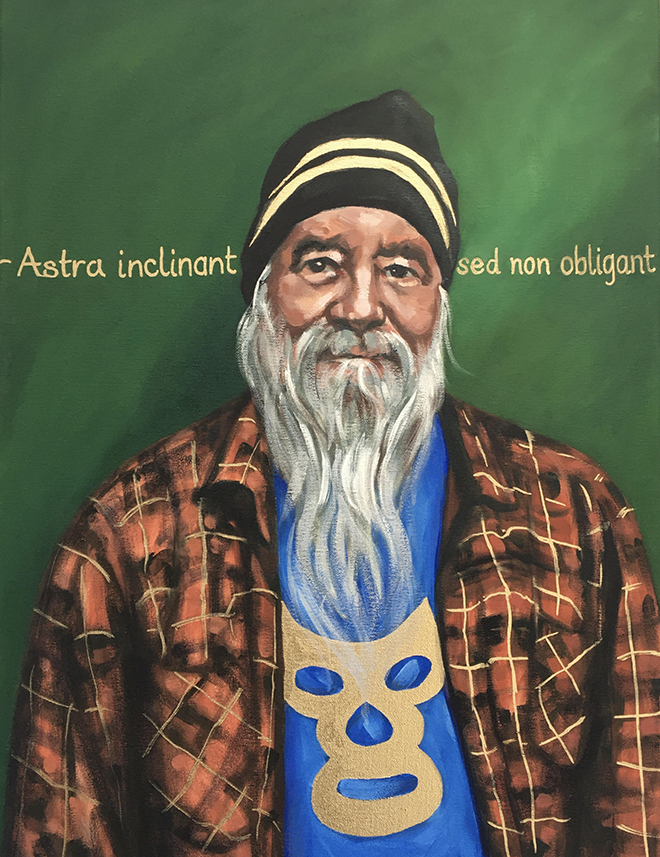

Image courtesy of Karen Jacobi.

Jose Vargas walks into my office about once a year to hand deliver flyers for art shows he organizes for the City of Dallas, sometimes bearing small gifts and always looking like a lama with his long hair, beard and calm demeanor.

He always has some astounding story about his life to share.

Vargas, 71, started putting on “El Corazón” art show annually in 1993, giving hundreds of local artists the chance to showcase their work over the past 25 years. The city’s cultural centers have been closed since the start of the pandemic, and this year’s “El Corazón” show is planned as one of the first in-person events at the Bath House Cultural Center this year. The show will feature about 50 artists whose work has appeared in past shows, sort of like a greatest hits.

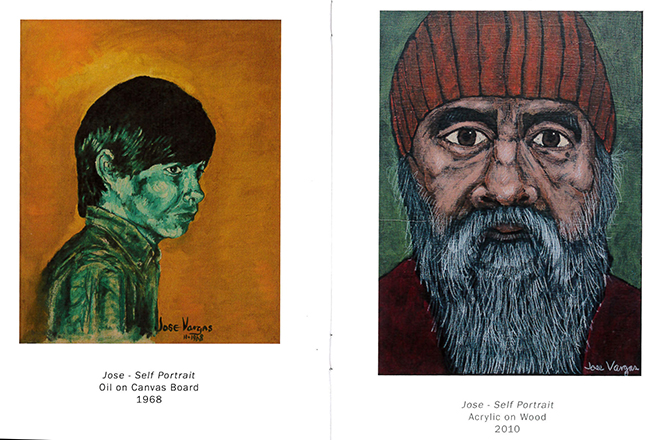

Vargas also organizes the annual Virgin of Guadalupe exhibit at the Oak Cliff Cultural Center, among other group shows. His 2017 solo exhibit in Oak Cliff featured oil paintings he did in the 1960s, alongside recent ones.

He attended Adamson High School and still lives in Oak Cliff.

On 25 years of “El Corazón”

I’m not sure we can call it “annual” anymore because I told them that I don’t want to do it every year anymore. I want to do it every other year. I have a lot of interests that I want to pursue. I’ve been [saying] that I’m going to die soon, and I just don’t know when. I made a list of things I want to accomplish, and one of them is that I want to explore other themes.

Hundreds of artists

Usually we have about 50 people in the show every year, so I deal with hundreds of artists. I came across this individual, Kelly B. Morris, who had a piece in “Corazón,” and I was really moved by it. So I met him. He lives in a small town about an hour and a half from here, and he’s a teacher. I looked at his work, and I was just blown away. I said, “I’m going to do my best to get you an exhibition.” But this guy is really passionate about his art, and he’s really working from his heart. I said, “What if I started focusing on one or two individuals, and that will be the ‘Corazón’ show?” I wanted to do something different, and there it is.

“El Corazón” started because of a cancellation

I used to go see a lot of bands at Club Dada, and it was an art gallery back then. I became friends with the bartender, who also ran the gallery. One day she called me, and she said, “Jose, I’m really in a bind. I had someone cancel, and I need something in two weeks. Can you help me?” I said, “Sure,” so I started measuring the walls to see how many pieces we needed. Lucky for me, I had just organized the first Our Lady of Guadalupe show, in 1992, so I contacted a lot of the same artists that were in that show. One of the artists I invited happened to be Terry Aguilar, who was the director of the Bath House Cultural Center at the time. She said, “Would you consider doing that show at the Bath House Cultural Center?” So I went to look at it, and of course, I liked it, so I said, “Let’s do it,” and it became the most popular show the Office of Cultural Affairs does. Well, actually, the most popular show now is “Día de los Muertos,” but it’s not a competition, even though it kind of is.

What “El Corazón” means to him

It’s the heart, and it’s the human heart. All of the pieces have to have a heart in them, and I don’t want them to be sweet. People associate it with Valentine’s Day because it happens to be in February, and that’s OK, but it’s not a Valentine’s Day show. I want the real human heart, not candy and flowers that get thrown away and forgotten. I want a big, bloody heart that’s in your face. The idea for the show came from lotería, the Mexican game that’s like bingo. Card No. 27, el corazón, is a big, bloody heart with an arrow in it, and it’s floating in the air. It’s very surreal. When I saw that, I said, “Now, this is art.” This is art I can relate to. Everybody’s had a wounded heart sooner or later. Give me a broken heart, a heart that’s been set on fire or stomped on, because that’s really emotional. I don’t mind flowers and things that are considered pleasant as long as it’s not too sweet.

Breaking hearts

We have about 50 artists every year, which means I have to reject hundreds of entries. People get really upset with me, and they stop talking to me, and this can go on for eight, 10, 12 years. Enrique Cervantes has been in charge of the gallery at the Bath House for 18 years or so. I consider him the “nice guy.” When the work comes in, and you’re dealing with 50 or 60 artists, and people start asking a lot of questions, you get a little frazzled. I have a strange sense of humor. I say, “Enrique is the nice one.” I’m the other one.

Making connections

I’ve always been lucky that I’ve met people. In 1975, I went to college at El Centro and took photography classes. Right across the street from El Centro was this place called Tolbert’s Texas Chili Parlor. The owner was [journalist Frank X. Tolbert], and he started the first chili cookoff in Terlingua, Texas. I started hanging out there with my friend from photography class, and [Tolbert’s son, Frank Tolbert II] said, “Hey man, we really need help with bussing tables. If you clean up these tables, I’ll give you free beer and food” and however much money. I can’t remember how much it was. So that ended up being two years that I worked there.

Live music

When I was working at Tolbert’s, one of the managers was from Austin, and he said, “Why don’t I bring these musicians up from Austin, and we won’t have to pay them, we can just give them the door.” So he brought these guys up, and I ran the door. We charged $2.50 per person, and the first show was Jimmie Vaughan and the Fabulous Thunderbirds, before they were famous. We had Stevie Ray Vaughan. The first time I saw him, I just stood there, like, “This kid is really good.”

Why he went to college

I ran into a nephew of mine, because we have a big family and I have a lot of nieces and nephews around, and he told me he was in college. I said, “Really? You, in college?” He said, “Yeah, it’s full of good-looking women. I’ve never met so many women in my life.” So, I said, “Hmm.”

Why he dropped out of Adamson

They were drafting people for the Vietnam War. My art teacher at Adamson was Hattie Wilbur, and she became a really big supporter. I’ve always been a little bit of a rule-breaker, and whenever she gave us an assignment, I would always do the opposite, and she always liked it. I was supposed to graduate in 1968, but I dropped out because of the draft. But I was drafted anyway in July of 1969, and I became a cook in the Army for two years.

Life as a muse

Something bad happened to me, and I quit painting for 30 years. I used to paint with oils, and I had a wooden box with art supplies. I don’t want to go into it, but some of my best artwork was stolen from me. So I put everything in the closet and closed the door, and I knew it wasn’t going to be opened anymore. I felt traumatized. It was sort of a fight-or-flight kind of mode of protecting yourself. And the way I decided to protect myself was to stop painting. I started getting heavily into photography, but in the back of my mind, I kept thinking about it, and that’s one reason I started organizing shows, because I want them to keep painting. Sometimes I ask people to be in a show, and they say they don’t know what to paint. I’ll go to their studio or home and start looking around, and I’ll say, “What about this painting over here. You could do this and this with it,” and I can see their wheels start turning.