No one takes animal casualties harder than the keepers at the Dallas Zoo, so three giraffe deaths in a month’s time — and five in the past six years — is taking a toll.

Illustrations by Jessica Turner

Humans of Oak Cliff can tap into that sense of awe that accompanies proximity to an ocean, mountain range or grand canyon without leaving the neighborhood.

Cross I-30 and enter the Dallas Zoo. Think that’s overselling it? Try this.

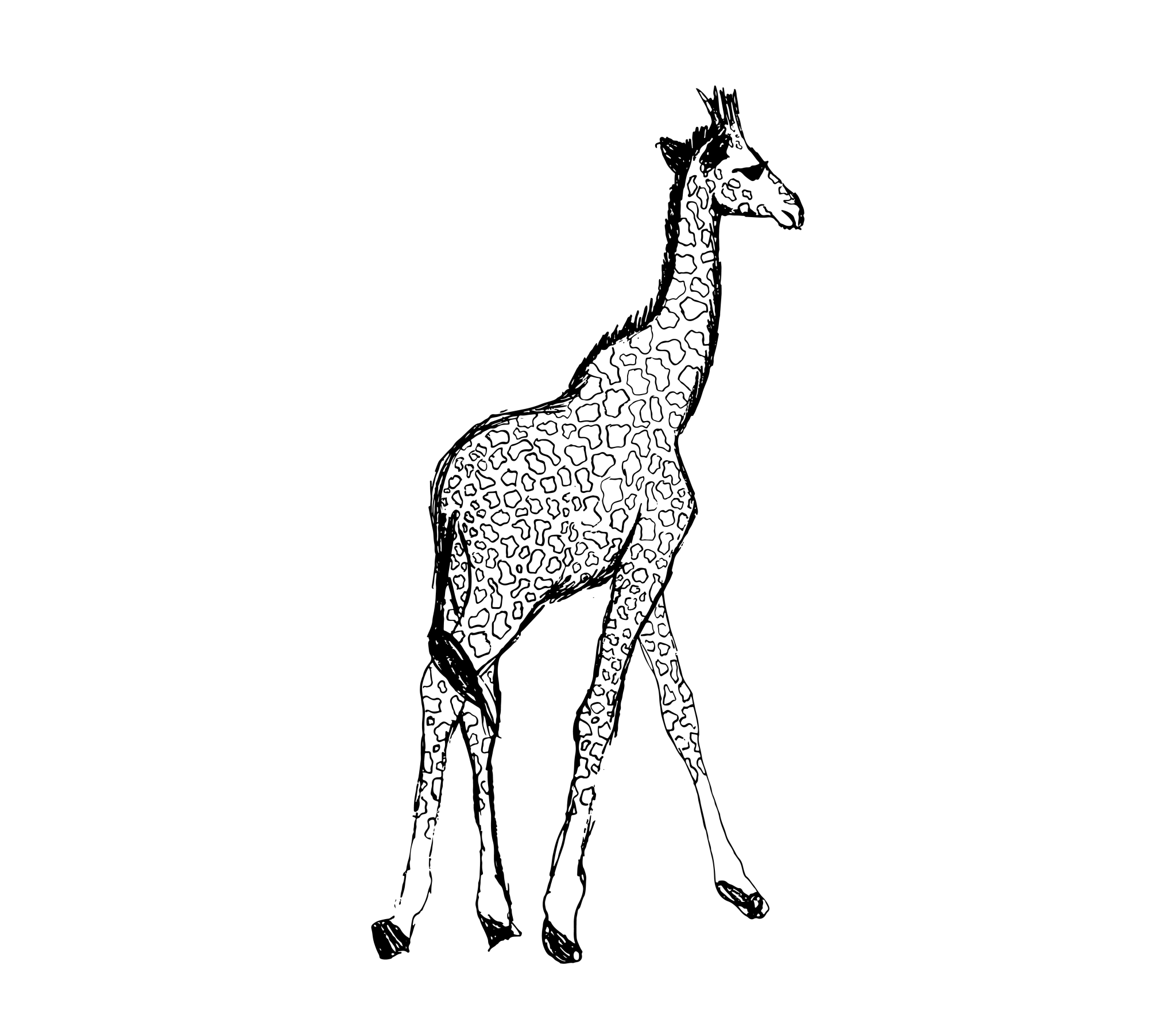

From the feeding platform overlooking the Giants of the Savanna exhibit, lock eye-to-obsidian-eye with Tebogo, the friendliest in a dwindling herd of reticulated giraffes.

Scratch his knobby horns, called ossicones, used to defend himself in territorial disputes. Marvel at all 18 feet of him, at least 35% neck, coated in that tawny-ivory pattern that resembles a cracked desert floor. Befriend this nuzzler of necks, nibbler of hair, chewer of smartphones (though he prefers lettuce).

The world looks different after an encounter with this bull, his sky-scraping fellows and the elephants, zebras, ostriches, impalas and guinea fowl that share his plain.

But, the Dallas Zoo has had a run of tragedy within its giraffe population.

In the past six years, three calves have died, one in October, followed by two adult deaths.

On Oct. 3 Marekani died at six months, a result of an accidental collision while running.

In 2019 Witten, a 1-year-old giraffe, died while under anesthesia. Baby Kipenzi died in 2015 after a collision and a broken neck.

The late October, early November deaths of Auggie, 19, and Jesse, 14, could be connected, according to the zoo. Necropsies pointed to liver damage, leading vets to focus on the possibility that they were exposed to a toxin through a food source, item in the exhibit space or a foreign object.

Doctors also are testing for zoonotic diseases and working along with experts from across the country to analyze lab test results on blood, tissue, food, plants and other items. They removed several plants as a precautionary measure and have ruled out a couple possibilities, including the COVID vaccine. Dallas Zoo has not begun to inoculate the animals against COVID and is on a waiting list to receive doses. The zoo also eliminated encephalomyocarditis, a disease of interest, but are still awaiting results on other zoonotic illnesses.

Zoo personnel are working every angle to prevent further casualties, but they say they are confident they’ve eliminated possible risks and feel “very confident” allowing animals back into the habitat.

Inside the zoo

We visited the Dallas Zoo following Marekani’s injury-related euthanization, before the two adults’ deaths.

Matt James, the Oak Cliff resident who oversees the zoo’s animal care team, points out that the Dallas Zoo has raised several healthy giraffe babies.

In the wild, about 50% of calves die in the first year compared to a little under 25% inside a managed care zoo, he says.

Still, he takes losses hard. These events can be so devastating to the zoo personnel that psychologists come in when an animal dies.

“Losing three calves in six years is really hard on us, but the more unfortunate thing is we cannot point to a single cause and go fix it,” James says.

An investigation — utilizing cameras placed in the barn and around the range — follows an injury. Plus, the team reports to an accrediting body called the Association of Zoos and Aquariums, which means close oversight and annual in-depth inspections.

AZA president and CEO Dan Ashe says animal care and health is foremost for every one of its accredited facilities.

“Dallas Zoo is keeping us informed and consulting expert colleagues throughout our community of members to help understand the highly unusual and tragic giraffe deaths that have occurred recently,” he says. “We have every confidence in their professionalism, their dedication, and in their ultimate success.”

Internal and external investigations reveal none of the calf deaths have been caused by neglect or wrongdoings by the zoologists and veterinarians on the animal care team.

Still, the staff never stops seeking improvements to animal safety and well-being, James says.

“With Witten, Kipinzi and Marekani, each incident was a unique situation. We try to learn and mitigate the risk,” he says. “The mortality rate is still much higher than we would like and we want to continue to find ways to get that first-year mortality to be as low as possible.”

Tempering the giraffes’ freedom to gallop amid the desert brooms and weeping love grass of the pseudo sub-Saharan range while also monitoring their welfare presents a challenge.

“It’s a dynamic group. We try to give them as much space as possible, but with those freedoms there are unfortunate accidents,” James laments.

Under the AZA’s supervision, Dallas’ zoo participates in a Species Survival Plan Program — there are some 500 species involved in these programs whereby accredited zoos and aquariums breed and transfer animals in an effort to keep their respective populations alive and healthy. James points out that in the wild, giraffes are undergoing what many experts have come to call a silent extinction.

“Giraffes are going extinct in the wild at an alarming rate … driven by wildlife disease and habitat destruction,” he explains, and he says the SSP is vital to creating sustainable populations.

Zoos in the program are building what he calls a Noah’s Ark, an “insurance population” for animals whose extinction will occur in the wild because, he says, many of the species in the zoo’s care will go extinct in our lifetime.

Animals born and raised in zoos will live their lives in managed parks. Not in the foreseeable future, but someday, “when we can figure out all of our wildlife issues” we can start repopulating the wild, James says.

Zoos also facilitate the relationship between humans and wildlife. Getting people to conserve habitats and endangered species means making them care, James explains.

“Connect, care and conserve,” he says. “If you can connect people with the animals and get them to care about them, they’ll learn to change their habits to support conservation programs, and they’ll help us conserve these animals.”

That’s where the zoo’s communications and marketing manager Chelsey Norris (also an Oak Cliff resident) comes in. The zoo’s public relations policy is to share, by way of social media, details about park successes as well as calamity.

Norris seems genuinely eager to educate the masses about the zoo’s inner workings, challenges and champions. “Masses” is no exaggeration. Her update about Marekani garnered 7,000 comments in less than 24 hours. And they are not all nice.

“Our whole policy on social media is to get people to connect with our animals and to share the story about how much good work we’re doing, but a part of that is that people get very attached to our animals,” she says. “We have to let them know when something happens. We encourage every conversation because within them are questions and we want to respond even if we don’t have all the answers.”

Outside the zoo

For another perspective, we spoke with Marc Bekoff, a biologist, ethologist, behavioral ecologist from University of Colorado who has toured the nation talking about animal welfare.

He has a problem with the idea that giraffes are born into zoos, kept in zoos and will never leave the zoos. Bekoff does not necessarily deny the conservation and public-awareness benefits that zoos and aquariums can offer, but he is concerned that animals in captivity have lost the freedom to be who they are.

No matter that the Giants of the Savanna was named one of USA Today’s best zoo habitats, Bekoff says it is impossible to reproduce their natural terrain.

“You can’t replicate in captivity what they need in the wild,” he says.

He says funds supporting zoological and breeding programs would be better spent on preserving the natural habitats in Africa. He adds that the use of animals as conservation “ambassadors” is disingenuous, because the creatures are “very, very different” in a zoo than they would be in the wild.

The scientist and award-winning author who pals around with Jane Goodall concludes, “Dogs want to be dogs; giraffes want to be giraffes.”