Photography by Corrie Aune

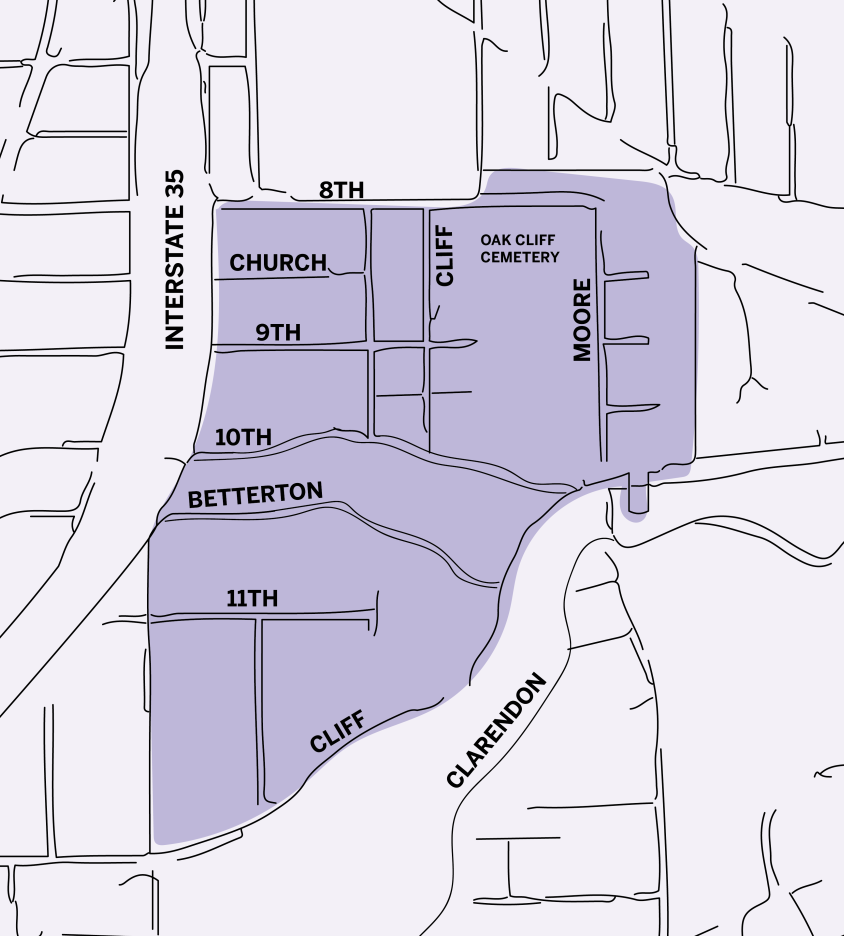

One thing the Bishop Arts District has in common with the Tenth Street Historic District: They are both part of the original town of Oak Cliff.

Interstate 35 took a chunk out of our neighborhood, all but eliminating its original business district and forever bisecting Oak Cliff in 1956.

Before that, Patricia Cox remembers that she and her family could walk as far as Zang Boulevard without stepping out of the embrace of Tenth Street.

The white part of town began west of “Zangs,” as Cox, 78, and many Oak Cliff natives still call it. On the other side of what is now Cliff Street, residents used to call the police on Black kids who deigned to enter their vicinity, she says.

To the north of Tenth Street is The Bottom, where seasonal flooding of homes was part of life for generations.

Now plans for the $82-million Southern Gateway deck park are underway nearby, but the City of Dallas has never adopted a comprehensive plan for Tenth Street.

Neighborhood residents recently wrote their own plan with the help of the Inclusive Communities Project.

The 109-page document names discriminatory policies and financial disinvestment as unaddressed social injustices.

“Restorative justice is recognizing that residents should benefit from the improvements happening in the City of Dallas, especially those adjacent to the neighborhood,” the plan states. “The influx of capital happening near the neighborhood should benefit residents and not perpetuate displacement.”

Freedman’s towns called “Tenth Street” since the founding of Oak Cliff in 1887 once comprised an estimated 300 acres. The geographic boundaries of the Tenth Street Historic District encompass 69 acres. But this national treasure’s place in our city’s culture and history cannot be measured.

Oak Cliff’s beginnings

Some of the earliest Black residents of Dallas were brought to what is now Oak Cliff as chattel of European settlers. A family of three enslaved people, a father, mother and child, arrived with William and Mary Hord in 1845. Their settlement became known as Hord’s Ridge.

An earlier settler, William S. Beaty, deeded the 10 acres that is now Oak Cliff Cemetery, where there are African American graves dating to 1844.

Grocery wholesaler Thomas L. Marsalis, the founder of Oak Cliff, purchased 2,000 acres, including Hord’s Ridge, to realize his dream of developing a suburban paradise in 1887. The 150-acre Marsalis Park, which is now the Dallas Zoo, had a lake and amphitheater for performances of theater and opera.

Marsalis and business partner John S. Armstrong, operating as the Dallas Land and Loan Co., brought the vision of an exclusive residential and resort community to our side of the Trinity River, but they had a falling out.

Armstrong went on to develop Highland Park. Marsalis invested about $1 million into Oak Cliff. Besides Marsalis Park, there was a steam-powered railway across the river, the luxury Park Hotel with its artesian wells, Lake Cliff Park and the homes of Rosemeade Place.

Marsalis wound up going broke in the Panic of 1893. He sold off a bunch of real estate and was never heard from again. Genealogists have since found that he died in Patterson, New Jersey, in 1919.

Who Lives in Tenth Street?

Total population: 1,407

44% Black or African American

54% Hispanic or Latino

1% white

517 households

91 vacant structures

30% owner occupied homes

70% renter occupied homes

43% of residents live in poverty

$27,227 is the median income

Freedman’s town

Col. W.J. Betterton, a veteran of the Confederate Army, purchased four acres near the cemetery from William Brown Miller in 1887. A Black man, Anthony Boswell, purchased lots on what became known as Miller’s Four Acres the following year.

Those 4 acres encompassed Oak Cliff’s African American homeownership boundaries until the Panic of 1893 sent tourists packing and opened more real estate to Black buyers.

“Tenth Street was self-sustaining,” says resident Shaun Montgomery, who grew up in the neighborhood. “They didn’t have anything in the beginning, when they came over in the 1860s. So they basically had to make it out of whatever. They could only go in certain areas, so it ended up being a self-sustaining community.”

Tenth Street grew to include churches, N.W. Harllee school, a doctor’s office, a funeral home, a cleaner’s, a drug store and soda shop, a grocery, a cobbler, barbershops and a blues and jazz café. There was even a movie theater at the retail center known as Show Hill, near what is now Townview high school.

The neighborhood is steeped in music history.

The father of rock ‘n’ roll guitar, T-Bone Walker, aka Oak Cliff T-Bone, grew up in this neighborhood with musicians who originated the Trinity River blues. Walker’s stepfather was a musician in the Dallas String Band, and Walker accompanied family friend Blind Lemon Jefferson to gigs in Deep Ellum. Ray Charles lived in Wheatley Place in South Dallas, but he later collaborated with jazz saxophonist James Earl Clay, who was born and reared in Tenth Street.

The neighborhood became an historic district in 1993 under the leadership of neighborhood resident Mamie McKnight, who died in 2018.

It is one of the few historic freedman’s towns remaining in the United States and is on the National Register of Historic Places because of the cultural significance in its architecture and history.

Tenth Street was home to Oak Cliff’s first City of Dallas certified historic landmark, the Elizabeth Chapel CME church, but it was torn down in 1999.

Historical inequity

Larry Johnson grew up in Oak Cliff and used to ride his bike through Tenth Street to school at Townview in the ’90s, but he didn’t know where he was.

This was amid the crack epidemic, which disproportionately affected Black urban neighborhoods, and nearly every business in Tenth Street had closed.

Decades of redlining, starting in the 1930s, meant banks wouldn’t lend money to homeowners or buyers in Tenth Street. Homes fell into disrepair. Younger generations migrated to California. Homeowners died, sometimes without wills or deed records.

Johnson became interested in preserving the neighborhood around the time the City of Dallas was summarily demolishing vacant houses based on an ordinance, since restrained, that allowed homes 3,000 square feet or smaller to be torn down if they posed any kind of safety threat due to neglect.

“Places like this are disappearing in this country,” Johnson says. “Our history is disappearing.”

Johnson and his wife recently bought a house on Betterton Circle, which he is renovating himself, and they plan to live there with their five kids eventually.

That is only part of his dream for Tenth Street.

What Johnson really wants, in a few words? African American Colonial Williamsburg. A living museum of African American history, full of renovated houses and biographies of the freed slaves who were their original owners and of the other families and businesses that have made Tenth Street what it is for 134 years.

1131 Betterton Circle in 1980. Photo by Steve Wallace for the Texas Historical Commission, via the Portal to Texas History

Tenth Street now has about as many empty lots as occupied homes. Johnson wants to acquire old houses from other historically Black neighborhoods in South Dallas and move them to empty lots in Tenth Street to be renovated.

He also tracked down blueprints for the Elizabeth Chapel, which the city drew up prior to its demolition, and he recently applied for a grant, with help from Preservation Dallas, in the first step to having the church rebuilt.

Tenth street is not going to be saved by city policy or a charitable land trust, he says.

“Part of the experience of being Black in America is doing things without support,” he says. “You learn to do a lot with a little.”

Shaun Montgomery grew up in Tenth Street, in her great-grandmother’s house, and she says crime has to be addressed before her neighborhood can move forward.

The City of Dallas recently invested millions of dollars for infrastructure including sidewalks and streetlights in The Bottom, but Tenth Street residents say none of that has come to their neighborhood so far.

Montgomery’s big dream for Tenth Street is a library.

The closest locations are the North Oak Cliff branch or the Central Library, which are not convenient to Tenth Street or The Bottom, she says.

Her second wish is for homes to be restored. Many are over 100 years old and were built by the hands of freed slaves.

“There are some good, well-made houses in this neighborhood, to be able to withstand everything they’ve gone through,” she says.

Renovation and preservation

David Cervantes purchased a cottage at 201 Landis St. last year.

He paid $80,000 for the house, situated on a corner above Betterton Circle, and he expects to spend about $120,000 renovating it.

Cervantes, who emigrated from Mexico to the United States as a teenager, is a general contractor who frequently works on historic homes in old Dallas neighborhoods, including Winnetka Heights. He’s used to complying with historic district standards.

“I found the house in really bad condition,” he says. “It wasn’t easy, financially or in any other way, but it’s been worth it.”

After submitting renovation plans, it took almost seven months to get a certificate of appropriateness from the city’s Landmark Commission to start construction.

The house was boarded up, and the front porch had been removed. A previous owner had taken away the historic wood siding, which Cervantes had to replace with new wood.

He rebuilt the brick chimney for historic accuracy, even though he couldn’t afford to rebuild the fireplace.

The project could be finished this month, and he’s thinking about moving in with his wife, Jordan, and their three kids.

“The sad reality about these houses is they need a ton of work,” he says. “But they can be great little houses.”

Vigorous demolitions started after 2010, when the city implemented the 3,000-square-foot rule. Virtually all the homes in Tenth Street are smaller than 3,000 square feet.

In 2019, the Tenth Street Residents Association sued the City of Dallas under the Fair Housing Act, “for the disproportionate demolition of homes in their historic district compared to adjacent predominantly White historic districts.”

The lawsuit was later thrown out because of standing, but Dallas City Council suspended demolitions in Tenth Street for one year. That moratorium has not been renewed.

The National Trust for Historic Preservation granted the residents association $75,000 in 2020 to continue their preservation work.

“It is clear that preserving the existing housing stock in the Tenth Street Historic District meets the goals of preserving and increasing affordable housing units and protecting African American historical heritage,” the neighborhood-led plan states.

“Because of this, the neighborhood has organized to ensure that these goals are clearly articulated and inform policies and practices pertaining to the neighborhood moving forward. A lack of inclusion of the residents led to the disinvestment of the neighborhood today, therefore an inclusive vision centering the ambitions and vision of the neighborhood can lead to positive reinvestment in the future.”

What’s in the neighborhood-led plan?

On the advice of Murray Miller of the Dallas Office of Historic Preservation, the plan contains an architecture guide complete with drawings and examples of existing and demolished structures.

Other points neighbors made in the plan are as follows:

Green space — There is the cemetery. The deck park is underway, and Tama Park is just outside the district. But neighborhood residents want their own park inside the historic district.

Circulation — Many neighbors say they want speed bumps to prevent cars from speeding down their streets.

Zoning changes — Some of the businesses and amenities that neighbors want, such as a pharmacy, are not allowed under the current zoning. Neighbors want zoning that reflects historical uses. They also want the maximum building height of 36 feet lowered.

Preservation — “The historic district status should under no circumstances be repealed or amended in a way that harms the character and preservation activities of the district,” the plan states. Neighbors do not want the historic district boundaries to shrink.

Clarity — Neighbors want a clear guide on how to comply with historic requirements in building or renovation.

Title-clearing assistance — The city employed a private law firm to help clear titles throughout Dallas. But neighbors say more help is needed specifically in Tenth Street. Neighbors also need assistance in lowering their property valuations and tax bills. Lack of clear ownership prevents homeowners from benefiting from programs to help with home repairs.

Housing-repair funds — Residents need help with major home repairs, including plumbing, roof and foundation repair, windows, doors and siding. “Providing home repair grants through public and private funding and with historic preservation programming would enable residents to receive repair funds they need to preserve their home and personal comfort and safety,” the plan states.

Funding public services — Neighbors say Tenth Street needs streetlights and pavement improvements to streets, sidewalks and alleys. While the city has funded some of this recently, Tenth Street neighbors want a future bond allocation for capital improvements.

Investment in Black history — “The Historic District is a national treasure, and the history and culture of the district should be invested in and celebrated,” the plan states. A cultural center, museum, film festival or concert series are some ideas to achieve this.

Compatible infill housing — Apartments, condos and high-rises are not wanted by Tenth Street neighbors. They want the empty lots to be filled with small-footprint single-family homes.

Economic development — There are virtually no commercial businesses in Tenth Street. Neighbors want stores and restaurants, which could be attracted through economic-development incentives.

Property-tax relief — “It is likely that the deck park will increase property values and thus property taxes. These rising costs will make it hard to keep the houses affordable for residents with low and moderate income,” the plan states.

Nuisances — Tenth Street is downwind of one of the top 20 polluters in Dallas County, a WestRock papermill on Clarendon, according to state data compiled by Paul Quinn College. Neighbors want heavy industrial zoning removed from the area.

District 4 City Councilwoman Carolyn King Arnold, whose district includes Tenth Street, didn’t respond to a request for comment on the neighborhood-led plan.