Photography by Danny Fulgencio.

Buddy Barrow and Rhea Leen Linder exit his Ford F-150 and make toward the worn path to the Barrow gravesite in Western Heights Cemetery.

Passersbys walking on Fort Worth Avenue stop them with a question.

Linder, 84, and tiny as a bird, tells them, yes, this is where Clyde Barrow is buried.

She’s friendly and talkative. Rhea Leen was born Bonnie Ray Parker after her aunt, the notorious outlaw from Cement City whose story has touched millions of people the world over.

The aging heir to a notorious legacy, Linder made it her mission to move her aunt Bonnie Parker from Crown Hill Cemetery to Western Heights Cemetery in West Dallas to lie beside her love, Clyde Barrow.

Photography by Danny Fulgencio.

The final stanza of Parker’s poem, “The Trail’s End,” reads:

Some day they’ll go down together

they’ll bury them side by side.

To few it’ll be grief,

to the law a relief

but it’s death for Bonnie and Clyde.

By the spring of 1934, Parker and Barrow knew they were going to die at the hands of law enforcement.

Parker, who was married to Roy Thornton at 15 and never divorced, reportedly begged to be buried next to Barrow.

But her mother, Emma Parker, was heartbroken, and she refused. He had her in life; he wouldn’t have her in death, she insisted.

No one ever mentioned it to the Parkers again for decades.

Photography by Danny Fulgencio.

He can’t have her in death

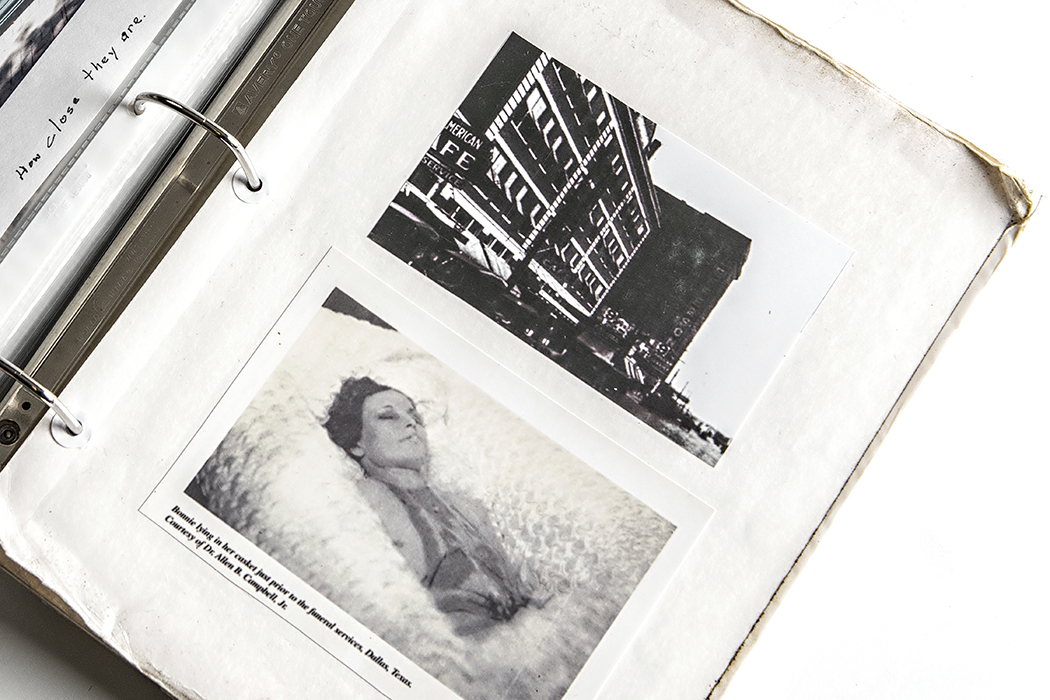

Following the bloody ambush near Arcadia, Louisiana, and a dramatic funeral in downtown Dallas, Bonnie Parker was buried in West Dallas’ Fish Trap Cemetery, 2 miles from the Barrow plot.

“It’s much nicer than Western Heights,” Linder says.

But she was moved again in 1945 to Crown Hill because of frequent vandalism. Crown Hill was close to the home of Billie Jean Parker, Bonnie’s sister, who raised Linder after her parents, both alcoholics, lost custody. Young Bonnie Ray Parker spent three years in a Houston orphanage and was 7 before Billie Jean, known as Jean, found her. Jean changed her niece’s name to Rhea Leen when she was in fourth grade to avoid ridicule.

The family never talked much about her aunt, and Linder says her first husband’s parents, who were from West Dallas, never knew about her connection to Bonnie Parker.

Linder had three husbands, who are all dead now. “I didn’t do it,” she quips. Laying down your life for a man doesn’t run in the family, she says.

“I can’t imagine being so dedicated to another person,” Linder says. “She chose to go with him, knowing what the end would be.”

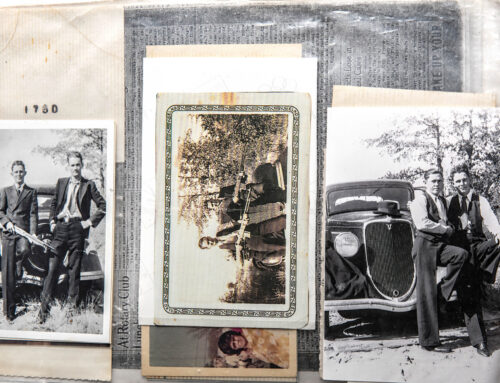

Her friends, Charles Heard and Sherry Childress of Lakewood, got involved with the Barrows in the 1990s. Heard bought Clyde’s death shirt, the one he was wearing when lawmen riddled their Ford sedan with bullets, from Clyde’s youngest sibling, Marie. He later sold it to a casino, but they all became friends. Heard used to help Marie and Blanche Barrow, Buck’s wife, with auctioning memorabilia and booking gigs to sign autographs at conventions.

He was afraid the topic of moving the graves was taboo with the Parkers, but his wife, Childress, had no such reservations.

The day they met, Childress asked Linder why Bonnie and Clyde weren’t buried together. At first, Linder dismissed the idea.

Now she’s convinced moving the grave is the right thing to do. Bonnie and Clyde were criminals. But they’re also American folk heroes. Rhea Leen and Buddy have heard from their ancestors’ “fans” all over the world. Most think they ought to be buried together, they say.

If they’re going to do it, it’s got to be soon. Linder had two children, but her son died in an accident in his 20s. Her adult daughter has no children. They are the last of the Parkers.

Photography by Danny Fulgencio.

The Trail’s end

The last time Bonnie Parker saw her mother was in early May 1934, a few weeks before her death. Buddy Barrow, who is the nephew of Clyde Barrow and son of L.C. Barrow, says the Barrow and Parker families met on a hill near the railroad tracks on Vilbig Road. That way, they could see anyone coming.

By then, Bonnie couldn’t walk. She’d sustained third-degree burns almost a year prior. Battery acid spewed all over her right leg after a car crash, and Buddy Barrow says the acid also caught fire. The burns were treated with baking soda, and she took medicine stolen from pharmacies, but she never saw a doctor.

The Barrows and Parkers drank whiskey and talked until 2 a.m.

Western Heights

Buddy Barrow says his family intended for Bonnie Parker to be buried in the Barrow plot. There is a space between Clyde and his mother, Cumie. Buddy even dug up a crepe myrtle tree near their headstones to make sure there’s space. Buddy Barrow says his grandfather used to keep a mower in the back corner of the cemetery and would walk from his filling station on what is now Singleton Boulevard to cut the grass. A DeSoto church that no longer exists legally owns Western Heights Cemetery, and some of its members still mow it. It has a historic marker, but the old cemetery could use some care.

While half-million dollar townhomes and luxury apartment complexes sprout up nearby, Western Heights cemetery needs fencing, walkways and lighting.

Photography by Danny Fulgencio.

Obstacles

Getting Crown Hill Cemetery to move its most famous resident might not be simple. The cemetery at first balked at the idea, and Linder even hired an attorney to figure out the legal obstacles. When WFAA reporter Jason Whitely asked the cemetery about it last year, they said the move would require a court order.

Even if Linder gains permission to move the grave, there is the matter of cost.

She and Barrow don’t have a plan to pay for exhumation, a new coffin, new headstones or a new burial. But they have ideas.

Could there be a benefactor with West Dallas investments who would pay for the move? With a new funeral for Bonnie, the whole thing could be made into a festival of sorts.

Would a production company or TV network be interested in making a documentary about moving the grave and, therefore, pay for the costs of the move?

Might a crowd-funding campaign have legs?

Meanwhile, Buddy Barrow and Rhea Leen Linder remain the family history keepers. And they’re longtime friends, often traveling together for TV appearances and as guests at festivals and conventions.

“My grandmother was so sweet, and she only lived 10 years after Bonnie died,” Linder says. “I always had resentment because of what they put their families through.”