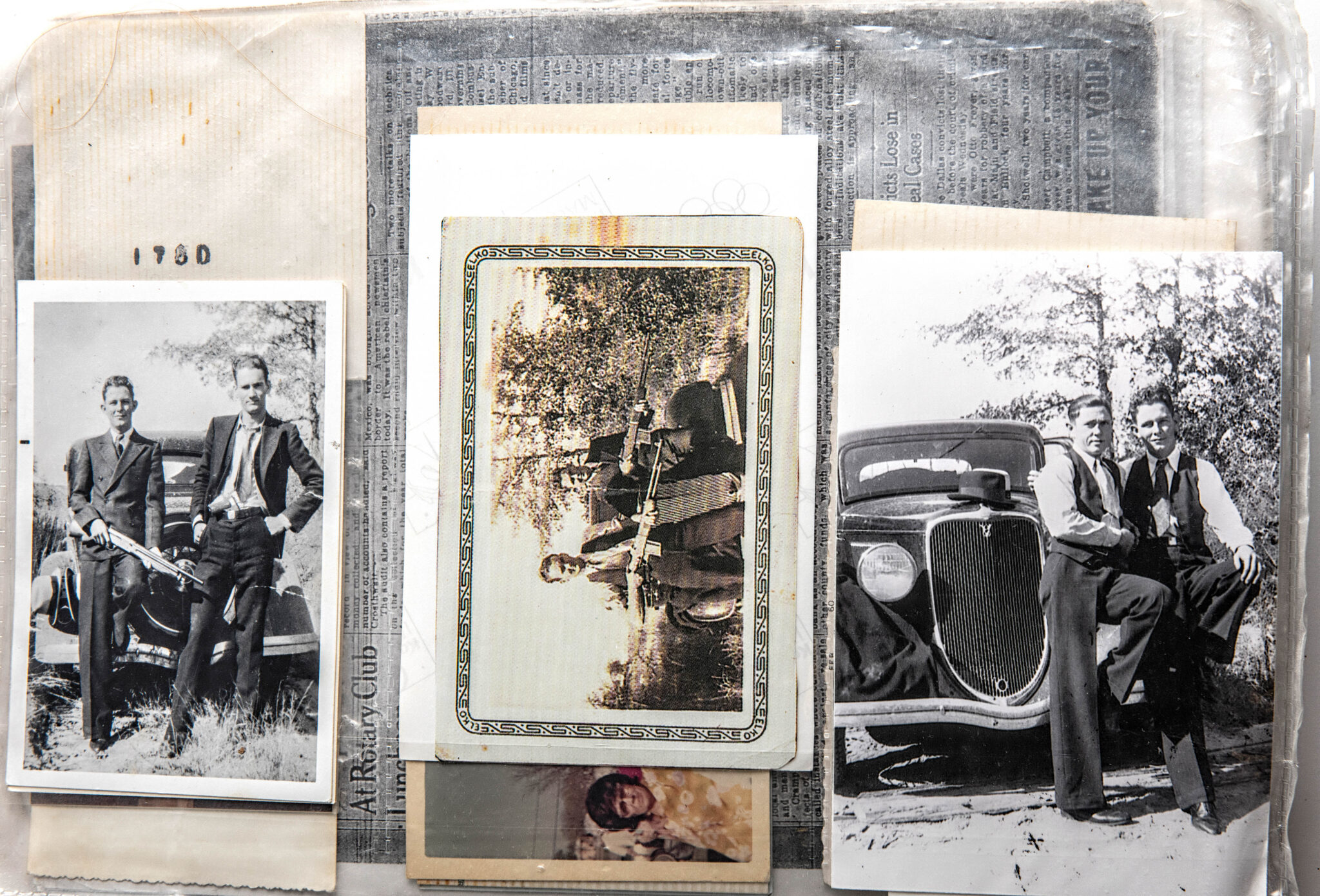

This month marks 90 years since the deaths of Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow, and their love story, rampant crime streak and downfall have maintained a cultural relevance through the decades.

There is no shortage of Bonnie and Clyde stories; the Advocate alone has published dozens. Movies have been made and a musical inspired by the folk heroes even reached Broadway.

But, despite the duo’s notoriety nationwide, it’s a history Dallas tends to shy away from. There is not a historic marker at any of the city’s “landmarks” associated with the duo, aside from their gravestones. In recent years, buildings they frequented have disappeared after failing to achieve historic designation.

Here are four pieces of Bonnie and Clyde’s lasting legacy that you may not know about.

Embracing the history

Dallas hasn’t erected historic markers for Bonnie and Clyde, much less a museum. But in Gibsland, Louisiana, The Bonnie and Clyde Ambush Museum still stands.

The museum was created out of a partnership between Oak Cliff resident Ken Holmes — whose father knew Dallas County Deputy Sheriff Ted Hinton who was part of the police posse that cornered and killed the gangsters in Louisiana — and Hinton’s son, L.J. “Boots” Hinton.

In 2009, Holmes told the Advocate that he’d hoped to open the museum in Downtown Dallas but couldn’t afford the rent.

Holmes died in 2012 and “Boots” Hinton died in 2016, but before their deaths they were considered some of the top Bonnie and Clyde experts and curators in the country. A highlight of their collection was the shootout car used in the eponymous 1967 film, which was featured in the museum until 2006 when Holmes had it moved to the Crime Museum in Washington, D.C.

The museum is still open, and a historic marker out front shares that the building used to be Ma Canfield’s Café, “Where Bonnie and Clyde stopped at 9 a.m. on May 23, 1934, picked up sandwiches and drove off to their deaths seven miles away.” That site of death is marked too, although the marker has been significantly graffitied.

Guilty as charged

Nearly a year after the duo’s death, 20 family members and friends were arrested by Dallas Police and federal authorities and charged with aiding and abetting Bonnie and Clyde. All 20 charged individuals either pleaded guilty or were found guilty, and the mothers of both gangsters each served a month in jail for their roles in harboring their criminal children.

According to a 1935 article from the Brownsville Herald, both women gave “mother love” as their reason for repeatedly visiting with their children, despite the warrants out for their arrests. At the end of the trial, Judge W.H. Atwell replied, “There is nothing in the law which gives mothers, sisters, brothers or friends the right to break the law.”

The most visited & stolen grave in West Dallas

Thousands of people visit Clyde Barrow’s grave at the Western Heights Cemetery each year, but keeping the headstone intact proved a challenge. The grave marker was repeatedly stolen in the late ’70s and early ’80s.

A 1979 article from The Paris News stated the tombstone was stolen five times in as many years, “usually around the time of the annual football clash between the University of Texas and Oklahoma University.” Clyde’s eldest sister, Artie Key, told the paper that the family had spent hundreds returning to stone to Western Heights Cemetery each time it was stolen.

“Lord, I wish they would leave it alone,” Key said.

According to Western Heights Cemetery volunteer Van Johnson, the tombstone is now embedded in five feet of concrete to prevent thievery.

“Someone would need a crane to get it out,” he says.

To preserve or to demolish? That is the question.

In early 2022, the West Dallas service station that was a home to Clyde Barrow and his family was demolished after slipping through the preservation cracks. The Landmark Commission did initiate a process to designate the building as a historic landmark, which protects a building from demolition for two years. That process began in March 2020, just days before Dallas County was overwhelmed by cases of COVID-19.

Two years later, the building was demolished.

A landmark process for another West Dallas home, the Lillie McBride House, was initiated at the same time as the service station. The home stood two blocks from the service station and belonged to the sister of a Barrow Gang member. It was where Clyde Barrow murdered Fort Worth sheriff’s Deputy Malcolm Davis in 1933, spurring the search that led to Bonnie and Clyde’s deaths a year later.

Some neighbors opposed historical designation for the home due to its bloody history. One West Dallas resident, Raúl Reyes Jr. wrote to the Dallas Landmark Commission that he opposed the home’s potential designation because its history did not represent the neighbors of West Dallas. Reyes also worried that approving a landmark designation would “force stewardship” of the building onto its owner, Wesley-Rankin Community Center.

In 2019, Wesley-Rankin executive director Shellie Ross told the Advocate that the organization’s board intended to demolish or move the dilapidated house after a series of break ins “raised safety concerns for the community.”

According to Ross, the home was relocated to Tyler, Texas, in spring 2023 at the request of Bonnie and Clyde’s living descendants. The home is now undergoing renovations, Ross said.

North of Houston, the “Bonnie and Clyde Bridge,” which was known to be a meeting spot for the gangsters, collapsed due to floodwaters this January. In a story similar to Dallas’, officials in Conroe City and Montgomery County attempted to historically preserve the bridge for several years before efforts fell flat.