Parents and teachers everywhere are concerned about returning to the classroom this school year. While some school districts have opted to go the virtual route this semester, others are having teachers teach in a hybrid format, meaning some students may be physically present in a classroom, if they wish, while others may remain at home and attend class via video conferencing.

Many teachers and parents would prefer that this semester be completely virtual, until COVID-19 cases dramatically decrease or until there’s a vaccine. As a person who is immunocompromised, a former teacher at an Oak Cliff elementary school took matters into her own hands.

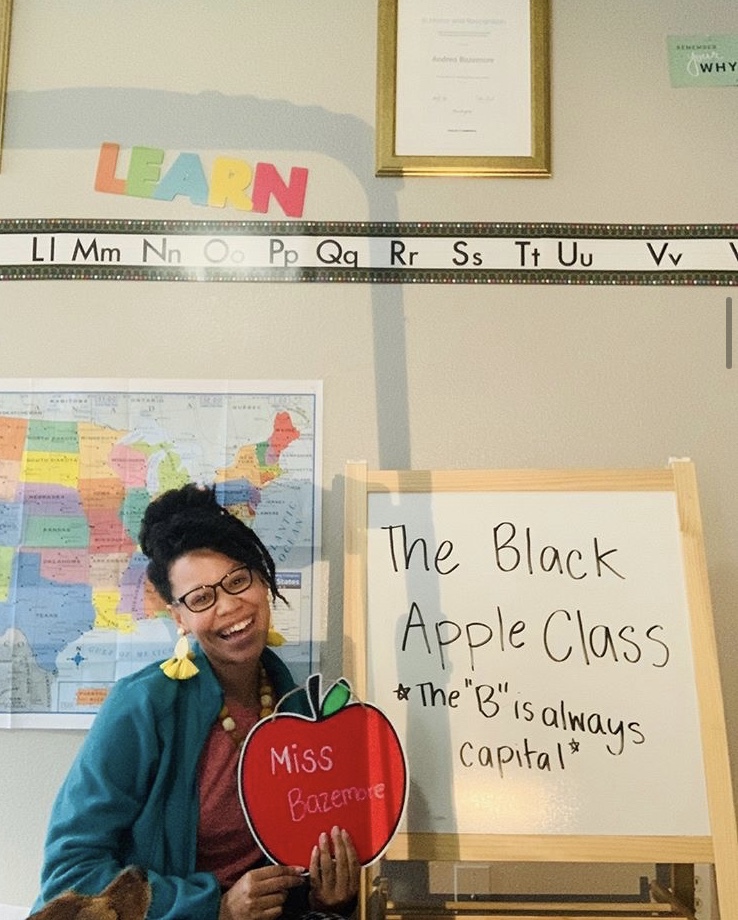

Beginning this fall semester, Andrea Bazemore will be teaching from her own virtual school called The Black Apple, offering anti-racist, unbiased and culturally responsive curriculum. She was inspired to launch a virtual school after realizing that school districts couldn’t acquiesce to everyone’s needs.

“I think school districts are in a tough spot and I very much empathize with them,” Bazemore says. “They don’t want to put all of their resources into virtual learning because what if the virus passes? Then, they have to go around and spend more money to get ready for in-person instruction…It’s a tough decision school districts have [to make.] I don’t think anyone would want to be in this position. That being said, I don’t think school districts can possibly worry about the health of everyone and get it right. It’s just too large of a system. So, I have to look out for me. There’s only one of me.”

Former Dallas ISD teacher Andrea Bazemore has launched a virtual school called The Black Apple | Image courtesy of Andrea Bazemore

Some of Bazemore’s biggest concerns this school year increased rates of depression and anxiety for parents, students and teachers alike. She is also concerned about special education students who haven’t been serviced properly, as well as how far behind students are and will be.

In addition to her efforts to curb the spread of coronavirus, Bazemore is also on a mission to create a safer environment emotionally. Through The Black Apple, Bazemore will be offering social emotional learning. She will be delivering material packages locally and shipping them nationwide, all customized to the students’ personal preferences.

“We take SEL seriously and it’s not lip service,” Bazemore says. “For example, we take the whole week to have wellness workshops and emotional regulation. We have 25 minute technology sessions the first week of school where we spend only 25 minutes figuring out or edtech programs. Whatever programs we don’t figure out, we won’t use until October. There’s too much mental congestion right now. Too many decisions we have to make as people. This just helps streamline things and makes things more crystal clear.”

Bazemore plans to continue to teach virtually over the course of the next year. While she has an entire school year’s worth of curriculum planned out, other educators are uncertain what the next year entails.

This past summer, east Dallas resident Mess Wright was forced to adjust her fabrication lab operations for her summer science camps. She had originally planned to host WorkChops’ summer science camps online and was in the process of setting up a website where she could do it virtually. But after talking with her customers, she learned that most parents and children want to participate in the camps in a physical setting.

In her lab, the adults wore masks, constantly cleaned surfaces and tried not to go out to places that weren’t home or the lab. Wright, however, admits that the students, mostly elementary and middle school-aged, had a hard time keeping masks on and maintaining a six-foot social distance.

“I have to be honest, most kids couldn’t keep the masks on for very long,” Wright says. “They don’t want to wear them, or they’ll wear them wrong…I think that asking large groups of kids to wear masks all day is very unrealistic because we couldn’t even enforce it with a small group.”

In a pre-pandemic timeline, Wright would normally be using this time to plan out her camps and workshops for the remainder of the year. Now, she is planning events one week at a time.

While she wasn’t sure what to expect at camps this summer, Wright feels rewarded having given her students a place to create and learn. Like Bazemore, Wright notices higher levels of depression and anxiety among parents, educators and students.

“I think we did a really good job of not having the kids freak out or feel freaked out,” Wright says. “One of the biggest reasons that people told me they wanted in real life camp and not online camps is because they were struggling at home. People were either kind of depressed or at each other’s throats. Kids had anxiety. There was one kid that we had that was telling his parents every day, all of these cures and solutions he was coming up with for COVID and he’s only six years old. He was obsessing over that. And within three days of being with us, he wasn’t talking about that anymore.”

Some school districts plan to bring students and teachers back to the classroom by next month, while some have yet to decide. As such decisions are up in the air for the time being, the general consensus seems to be that schools cannot realistically expect students to adhere to COVID-19 safety guidelines.

“We couldn’t realistically have everyone wear a mask all day and keep them six feet apart,” Wright says. “It just doesn’t happen with kids under the age of 12. It’s just not a thing.”