Photography by JESSICA TURNER

When Jessi and Daniel Hall outgrew their previous home, they wanted a project.

Nothing already remodeled, they decided: Why pay for someone else’s upgrades?

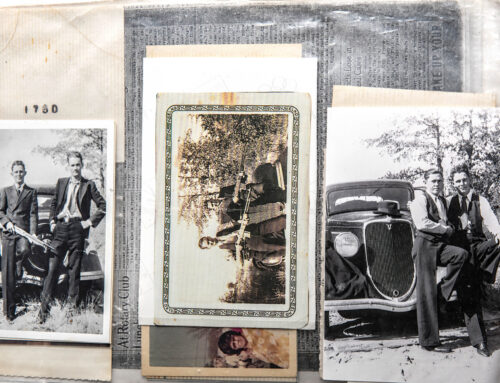

After a lengthy search, they found a dilapidated 1940s colonial revival-style house that sits off in a corner, not quite part of the Kessler Park subdivision. Rumor has it the home was moved to its current spot from an adjacent neighborhood.

“We were looking for something a little odd with some unique challenges,” says 35-year-old Jessi Hall. “And so this place was kind of perfect.”

After looking at three firms, the Halls first met Cliff Welch on the property on a Saturday in 2018. His firm, Welch Hall architects (no relation to Jessi or Daniel), specializes in modern new builds.

“I’ve been practicing for nearly three decades,” Welch says. “I never in my life thought I’d be doing a colonial revival.”

The home is protected by a conservation district, but the Halls wanted to simplify and modernize.

“It’s just got this really timeless, simple quality of the pitched roof, white clad, kind-of Texas vernacular farmhouse,” Welch says.

Blending the two styles and meeting the conservation district’s standards meant stripping decades of modifications down to the home’s original bare bones.

“Colonial revival was something that allowed for more flexibility. It allowed for a simplification,” Welch says.

The bay window in the front was removed, streamlining the facade. Plastic siding was replaced with traditional white board and batten.

“He immediately got what we had in mind,” Jessi Hall says. “And he was also extremely pragmatic and solutions-focused.”

The timetable was unusual. Texas laws disqualified the Halls from a traditional mortgage since the home had no cooling or heating system. They needed a construction loan, but to qualify, a lender needed to agree on a budget and a general contractor had to be hired before the real estate deal could be finalized.

Meanwhile, the house was rotting. There was little that was salvageable, and even the foundation needed work.

“Nothing in the entire house was plumb or square or level when we started,” Welch says. “When you’re working with something that was built back in the 1940s or even earlier, that’s a challenge to get things to look good and clean and work.”

Hidden behind a door with a barely functional staircase, a 500-square-foot unfinished attic sold the Halls on the house.

“It was figuring out how to rework things to access the belly of the attic to create some extra room and a playroom for their daughter, and really expand the house within the existing footprint,” Welch says.

Finishing out the attic increased the house’s square footage to a little more than 2,000 square feet. Repositioning the kitchen and dining area allowed for a view of a lush tree line and access to the most private corner of the lot, perfect for outdoor entertaining. A wall now divides the kitchen and dining room. The kitchen includes two islands, one of which doubles as a bar that helps divide the kitchen and living room.

“I wanted to accomplish kind of an open-and-closed layout. So if we cook and eat at our dining table, I don’t want to see the mess that I just made, or I’m going to want to clean it immediately,” Jessi Hall says.

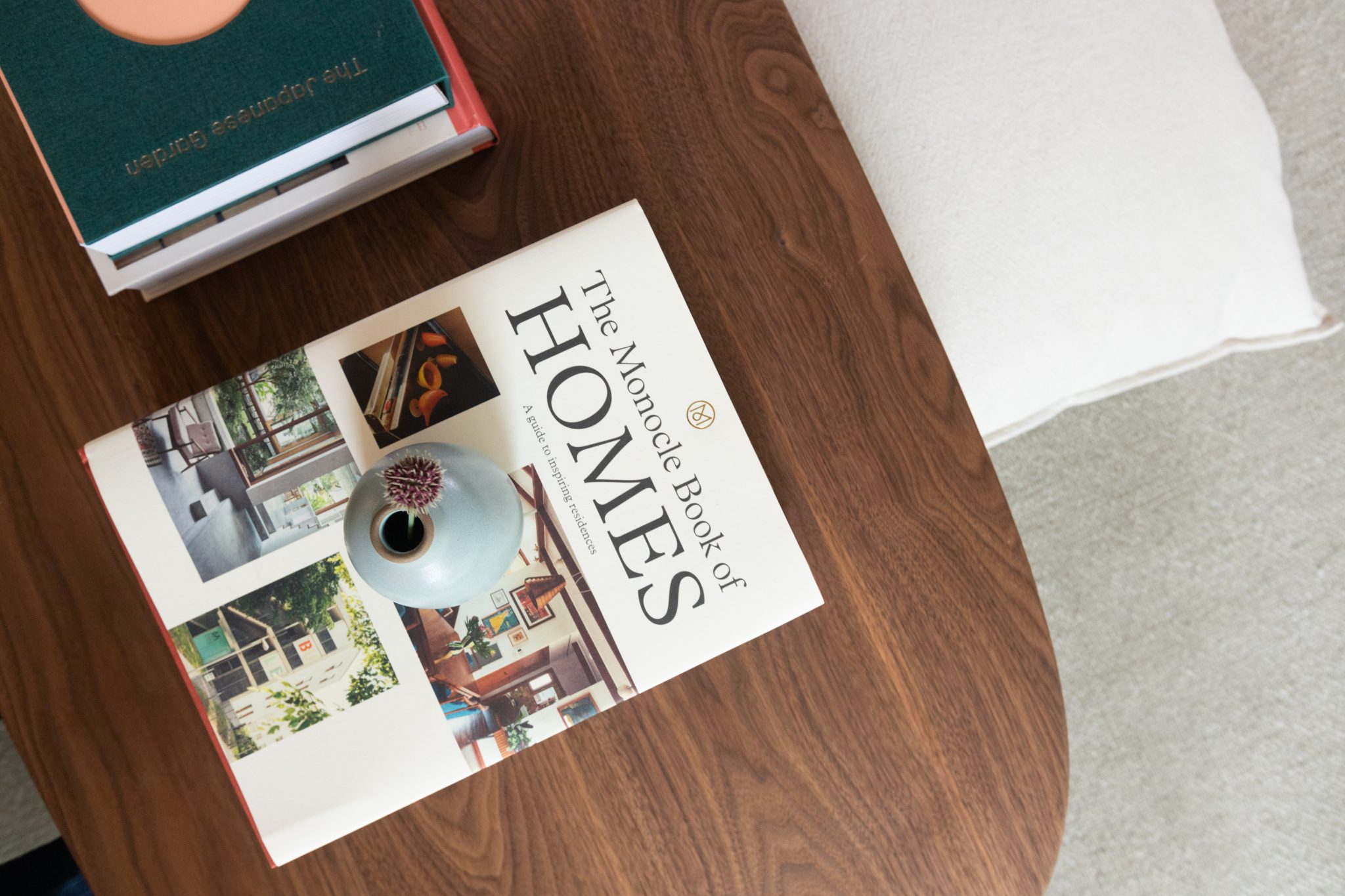

White oak is used throughout the home, from the floors to the wooden-slat room divider that creates a small entryway. Warm-tone wood pairs well with the couple’s preference for Japandi interior design, a combination of Scandinavian and Japanese design principles. The couple spends quite a bit of time in Japan, since Daniel works for Toyota; they spent three months living in a hotel in Japan during the construction phase while between homes.

“There’s a warmth and a simplicity and an attention to craft everywhere you look,” Welch says. “It’s a very understated subtle home, both on the inside and the outside. But there’s a real richness to the materials.”

A year and a half after beginning the project, the home was complete.

Most of the furniture is from their previous home. Hall found a pair of low-seat armchairs to reupholster; they came from an estate sale. The large, framed photo over the couch is an iPhone photo taken by Hall in Japan. They found another art piece in Jessi’s grandmother’s garage. A painting by Oak Cliff artist Charlie French hangs in the dining room.

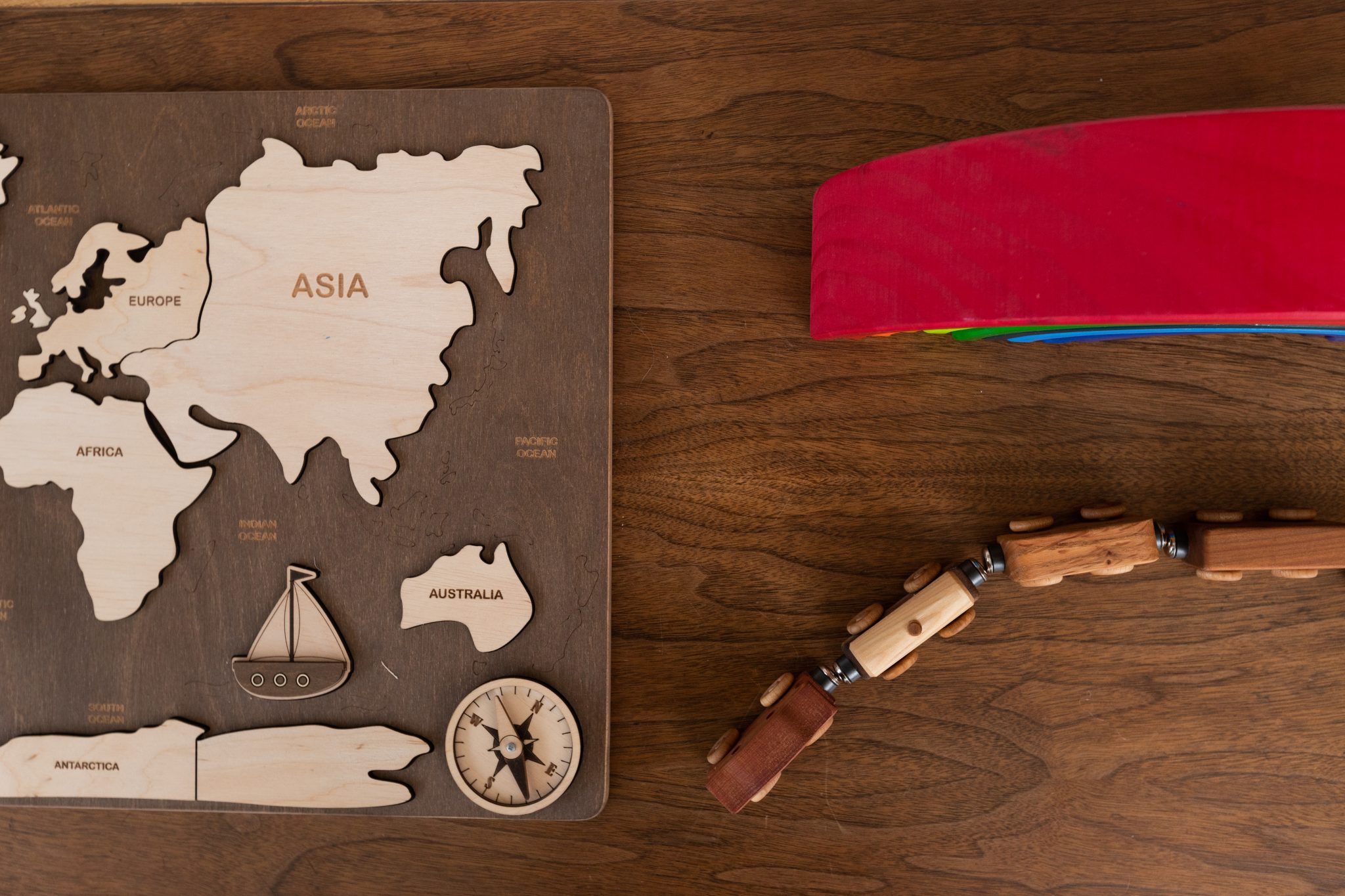

Their daughter, Sophie, has the run of the attic, which features a traditional Swedish wallpaper and a large reading nook tucked under an eave.

The 1940s Colonial Revival home sits at the foot of the Coombs Creek Trail. The property line abuts state-protected parkland, and a fence can’t be constructed.

“It’s on a really unique corner piece of property, where it just looks like it belongs here. It feels like it’s been there forever,” Welch says.

Since there’s no fence to keep trail users off their property, the lines between public and private are blurred. In one instance, a dog walker circled the perimeter of the home, coming right up against the windows and onto the back porch, Jessi says. But she says trail walkers mostly step onto the lawn to chat to the Halls as they swing their daughter in the front yard.

“I’m glad that we saved a building that other people wanted to tear down,” Jessi Hall says. “It’s rewarding to see something that was kind of an ugly duckling and think we can make this like a really nice part of the neighborhood and a welcoming property off the trail.”