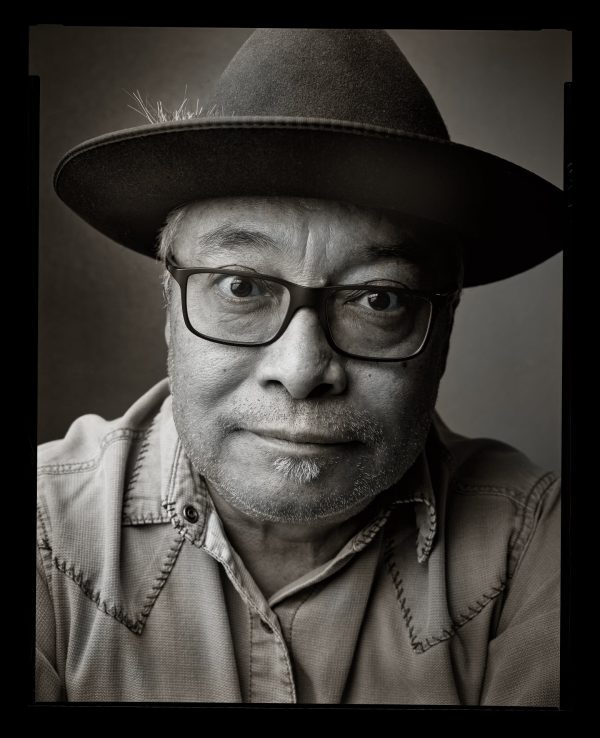

Portrait by Byrd Williams

Early versions of Manuel Pecina’s art photography employed one makeup artist and an assistant. Those were rough drafts.

The portraits of seven deities that comprise his Deidades, which shows at the Kente Royal Gallery in Harlem, New York, Nov. 3-21, required a small team, including costume designer Ricardo Alarcón, two makeup and body-paint artists, a hairstylist and an assistant.

The 20 pieces in the show were produced within the last two years, but he started making these realistic portraits of modern Mesoamerican gods in 2008.

And now this is the end.

“I’m going to retire it with those seven deities,” he says.

New York-based artist and end-of-life doula Marne Lucas is presenting the show alongside her own, Quietus, “black-and-white infrared thermal photography and collage works on paper exploring mortality, spirit and transformation.”

The two met because of her connection to Dallas as a former artist-in-residence at CentralTrak, the UT Dallas artist residency.

He recognized her Bardo Project immediately from reading about the realm that some Buddhists believe lies between death and rebirth, “bardo.”

Lucas partners with artists who have life-limiting illnesses, working to advance ongoing “legacy projects” like Pecina’s portraits of gods.

Ixchel as Jaguar, and Juracan by Manuel Pecina.

“I contacted her because I have a terminal illness, and my only cure is a lung transplant,” Pecina says.

Pecina was born in Rockwall and has always been a traveler. He’s lived in Spain, France and various parts of the United States. He moved from Los Angeles to Oak Cliff in 1993 and bought a house in North Cliff with his now ex-wife. They have a son, Sebastian, 22, who also lives in Oak Cliff and has two kids under 2.

Pecina’s art career has run parallel to one in computer science. Life in middle management funds life in art. Previously, he was in the aircraft industry, first working on military and commercial helicopters and jets, then on ambulance helicopters at Addison Airport.

“I used to fly around a lot and fix things that jiggled or made noise,” he says.

Then he started shooting airplane interiors as a commercial photographer and wound up getting a master of fine arts degree from UTD.

He describes himself as a “busy body,” meaning he can never sit still. From 2012-15 he owned and operated Ant Colony, a gallery at 417 N. Tyler St.

The opus culminating in Deidades started with his lifelong curiosity about religion. He was raised Catholic and is of Jewish descent on his mother’s side, and neither faith imprinted fully. Then he started learning about Mesoamerican religion, and he realized that was part of him, too.

“I just felt like they were three different religions that I was caught up between,” he says.

He was influenced by a book, David T. Raphael’s Conquistadores and Crypto Jews of Monterrey, which tells the story of Jews who avoided persecution during the Spanish Inquisition. That made him want to dive deeper into Mesoamerican religions.

The models’ stances and costumes in Pecina’s portraits drew from his study of books by an anthropologist, UT Arlington professor Julia Guernsey.

Ricardo Alarcón is a Mayan dancer who produced all of the costumes and headdresses.

“What we worship doesn’t matter, or it does matter,” Pecina says. “In the end, religion is there to provide a therapy for us, whether it’s meditation or prayer or chanting. It’s there to help us stay focused, stay motivated and maintain a certain motivation that helps keep us connected to the earth and helping to elevate others.”

Pecina first got checked in April 2016 because of shortness of breath. He says he knew he was in trouble when the doctor called about his test results and asked if he was a smoker, although he never smoked in his life.

The diagnosis came about five months later: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

It’s an environmental disease that results in scarring of the lung tissue, which makes it hard to breathe, and it worsens over time.

“It has nothing to do with autoimmune disease,” he says. “It’s not COPD. I’ve learned there are over 200 different pulmonary illnesses. I happened to be lucky enough to contract one they don’t know how to treat.”

He’s independent and loves to roam, but he keeps finding new limitations. This past summer, he drove from Texas to California and up the Pacific Coast Highway. He stayed in Washington state for a while and then drove back down, hitting Utah and Colorado. Driving alone over places with super-high elevation caused his oxygen saturation to drop considerably.

“I was lucky that I had my portable oxygen concentrator with me,” he says.

But it was scary.

“My new limitation is that I can’t go above 2,800 feet without oxygen,” he says.

His next trip will be to the Texas coast this winter.

He says he’s currently on about a dozen medications. One of them, an experimental drug called nintedanib, costs almost $10,000 a month, which he has a grant to cover.

His lung function has improved so much recently that he was downgraded on the transplant list. But he’s considering quitting the medications after meeting people in a support group who’ve lived 10-15 years with the disease already with no transplant or drugs.

He manages the anxiety that the disease brings through restorative yoga and opposite nostril breathing.

The images in the show were chosen this summer when Pecina and Lucas were in Los Angeles.

“It’s been helpful because art is one of the things that helps me forget about the illness,” he says.

Pecina, 61, considers himself retired, and he likes to take camping trips. He’s gotten really into making coffee outside, and he enjoys sleeping on the ground with no tent, under the stars.

The end of this series is not the end of his work as an artist. His home is currently on the market, and he wants to move into a live/work space where he can focus on his next project: modern portraits set in the Renaissance era.