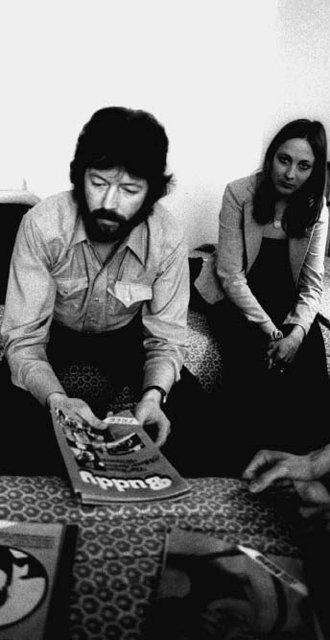

Kirby Warnock’s new film premieres this month. Dan Whiteman, left, is polishing the film. Photo by Danny Fulgencio

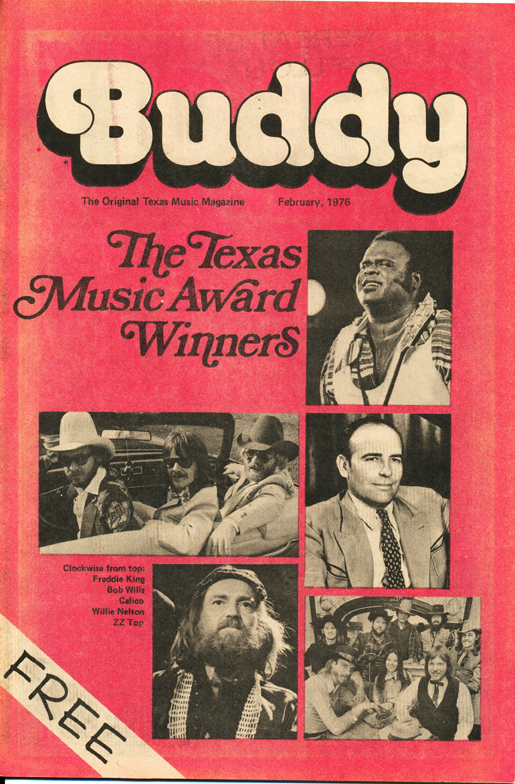

Oak Cliff-based filmmaker Kirby Warnock’s first film, the 1996 documentary “Return to Giant,” was a look at the 1956 film “Giant” from the perspective of the Big Bend area of West Texas, where it was filmed. The Mississippi native spent every Christmas and summer of his childhood in Fort Stockton, his dad’s hometown, and he always heard stories about “Giant,” which would inspire his first feature film. Warner Bros. picked up “Return to Giant” for distribution, and Warnock says he thought, “Well, this is easy.” Mild attention for his second film, “Border Bandits,” showed him otherwise, but he’s still at it. Warnock graduated from Baylor and moved to Dallas in 1976, where he was hired as an editor at Buddy magazine. His newest documentary, “When Dallas Rocked,” is a throwback to his Buddy years. It premieres Thursday, Sept. 26, at the Texas Theatre.

What is the story of “When Dallas Rocked”?

People don’t realize that back in the ’70s, Dallas was a bigger music city than Austin. Of course that’s not true today, but a lot of people don’t know this. [Rock ’n’ roll] was just a bunch of hippies playing music, so the media didn’t really cover it. It’s part of our history that just hasn’t been told yet. But there are lots of baby boomers who remember it.

Why was Dallas such a big rock ’n’ roll town then?

Because of the record industry here. We were the distribution hub for the entire Southwest. This was before the internet, before digital music, so if you heard a song on the radio that you liked, you either had to sit by the radio and wait for them to play it again, or you went to the record store and bought it. Dallas had distribution warehouses that covered the whole Southwest. If you ordered a record in Baton Rouge, La., it came out of Dallas. So anybody who was anybody, they had to come here because they could sell a ton of records. I’m not trying to say that we were bigger than New York or Los Angeles, but we were a close third. Back then, bands would skip Austin entirely and play Dallas.

Most of the photos from the film come from Buddy magazine. Tell us about that.

I was working at Buddy magazine, and I took most of the pictures in the film. There are also pictures by Stoney Burns and Ron McKeown, who were staffers at Buddy. We went to shows in Dallas and took tons of photographs. This was all before digital media, so you had to buy the publication to see the pictures. All these photos have been sitting in boxes for 40 years.

What was Buddy magazine?

Buddy started in ’73. It was named after Buddy Holly, and it’s still around, although it’s not quite the same. I’d say ’73 to the mid-’80s was its heyday. I was the editor from ’76 to ’83. The daily newspaper didn’t cover the live-music scene, and there was no alternative press. The Dallas Observer didn’t exist yet. So we were the only publication covering all that. We didn’t cover anything else; we just covered music. But we were the dominant publication. Record companies would beg us to come down and interview these artists who were playing in Dallas, because we were really the only outlet.

Who are some of the memorable people you interviewed?

I personally interviewed Eric Clapton, down at the Anatole. Don Henley, the Vaughan brothers, Elvis Costello. Elvis Costello played a club called Spaces … and we went to talk to him at lunch … there was no one else around. He told me he wanted to see Delbert McClinton, and I told him he was playing the Old Warehouse, which was on Mockingbird, that night. So after the [Costello] show, I went over to the Old Warehouse, and sure enough, he got onstage and jammed with him. These British bands idolized Texas bluesmen. All Eric Clapton ever talked about was Freddie King. I don’t think we in Dallas really appreciate that.

How did this film come about?

I made a teaser with the photos for the Oak Cliff Film Festival, and I got a huge response from it. It got a lot of hits on YouTube, and I got tons of calls and emails. So I decided to do a full-length documentary.

How long has it taken you to produce?

I’ve been working on it for the last nine months. I don’t have any money or funding. I have a full-time job [as a proposal writer for a consulting firm], so I work on it at night.