William B. Travis Vanguard and Academy for the Academically Talented and Gifted in Uptown. (Photo by Rasy Ran)

Who should lay claim to seats at Dallas ISD magnet schools? The most talented and gifted students in the district? Their siblings? The cream of the crop from each high school feeder pattern?

These were questions the DISD trustees debated at the board briefing two weeks ago, when they reached a consensus of no consensus. Tonight the board will vote on a policy change that addresses the issue of “sibling preference” at its elementary and middle school magnets — essentially allowing siblings to cut the line and gain admission to sought-after schools such as Harry Stone and George B. Dealey Montessori schools and William H. Travis Vanguard and Academy for the Academically Talented and Gifted (TAG). (UPDATE: The revised policy passed unanimously on Thursday night, Oct. 27.)

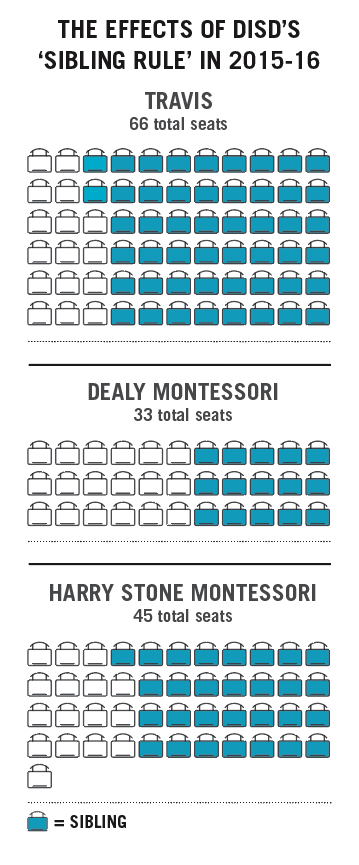

The issue first surfaced last spring when it was determined that of 66 available seats for fourth-graders at Uptown’s Travis, 50 spots went to siblings. At Dealey in Preston Hollow, 15 of 33 open seats were claimed by siblings, and at Harry Stone in southern Dallas, it was 29 of 45.

At Travis, the numbers were particularly striking in terms of how many qualified students were shut out: The 61 students on the waitlist had higher scores than 33 of the 50 siblings who were accepted.

At Travis, the numbers were particularly striking in terms of how many qualified students were shut out: The 61 students on the waitlist had higher scores than 33 of the 50 siblings who were accepted.

How the schools reached this point is a story that reaches back to the days of court-ordered desegregation, which ended in 2003, and the policies that followed. East Dallas Trustee Dan Micciche, in hopes of putting a stop to the sibling snowball effect, proposed an updated policy that would eliminate sibling preference and instead give roughly 1/3 of seats to applicants with the highest scores, and the rest to the top scorers from each of the 27 high school feeder patterns.

The proposal that will be voted on tonight, however, leaves siblings in the mix: It would still give siblings first dibs at Dealey and Stone and also give them a leg up at Travis.

Oak Cliff Trustee Audrey Pinkerton, one of the writers of the compromise policy, sent her children to DISD magnet schools — Harry Stone, Travis and Booker T. Washington high school arts magnet. Before the briefing, Pinkerton held a town hall meeting at Sidney Lanier elementary and proposed her policy to the 30 or so parents present, describing it as “an attempt to be middle-of-the-road.” Under the plan she crafted with Trustee Lew Blackburn, admission would change at Travis, with roughly 1/3 of the spots going to the top scorers, similar to Micciche’s proposal.

Where their proposals diverge, however, is that the younger brothers and sisters of current students are given an extra 5 points in the 100-point scoring system Travis uses, or “a little bump for being a sibling,” as North Dallas Trustee Edwin Flores puts it.

Flores, whose children attended Dealey, Booker T. and Townview’s TAG high school, keeping families together at the same school is important. He favors a plan that would still factor familial ties into TAG admission decisions, along with students’ GPA, test scores and admission exams. The five points would help make up for any test performances that could be attributed to “having a bad day,” Pinkerton explained at her town hall.

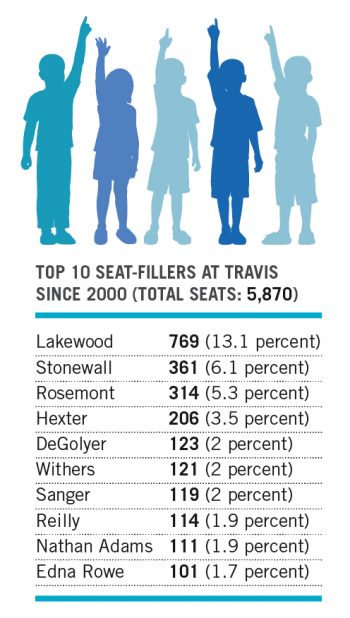

If approved, the policy should mark a slow shift in where Travis students come from. Last year, students from Lakewood and Stonewall Jackson elementaries in East Dallas claimed 143 seats — more than a third of the TAG school.

If approved, the policy should mark a slow shift in where Travis students come from. Last year, students from Lakewood and Stonewall Jackson elementaries in East Dallas claimed 143 seats — more than a third of the TAG school.

Rosemont Elementary in north Oak Cliff had 25 students at the school last year, roughly 1/8 of the campus. Rosemont trails only Lakewood and Stonewall in the number of students it has sent to Travis in the course of the magnet school’s history.

When desegregation ended in 2003, the district’s commitment to the courts was a magnet policy that would pull students from schools across the district in an attempt to continue the diversity the magnets had created. Last year, however, 111 of the district’s 152 elementary schools didn’t send a single fourth- or fifth-grader to Travis.

An updated policy could chip away at that number. “One thing people are worried about is, once the word gets out that a certain number of spots are available for all feeder patterns, there will be more competition,” Pinkerton said at the town hall.

We hope to ask Pinkerton about the people concerned by this, but she didn’t return calls yesterday.

Pinkerton doesn’t want to make any changes to admission polices at Dealey and Stone. Several Montessori parents at Pinkerton’s town hall meeting made the case that their schools have a different academic purpose than Travis, with more of a focus on families, and Pinkerton responded, “I agree with you that Montessori, the goals of the program are different.”

This poses the question of whether Dealey and Stone should have academic admission requirements at all. Trustee Miguel Solis broached this issue at the briefing, noting that “we may need to revisit the process of how to get into a Montessori.”

“That’s where I want to go,” Flores said via phone yesterday. “I want to get where we have eight Montessoris, and like the schools of choice, you apply and you get in with a lottery. Every kid has an equal chance.”

Mata Montessori in East Dallas is one of these schools of choice, which are lottery-based with some priority given to low-socioeconomic students and, in some cases, to the surrounding area. Like DISD’s magnets, its schools of choice have sibling preference, but starting next year, spots for siblings will be capped at 25 percent of open seats.

Both Flores and Pinkerton want to see more choices for families expand into neighborhood schools.

“If your McDonald’s has breakfast, lunch and dinner lines out the door, you open another store,” Flores said at a board meeting in June, and repeated the analogy at the recent briefing and in our phone conversation. “Expand this concept so there are a lot of places and options and competition — so we’re not having discussions about turning kids away, we’re having a discussion about having a waiting list of two.”

Pinkerton, too, is hopeful that neighborhood schools can become more attractive to families.

“You’re here because you feel like your child isn’t getting what they need at their neighborhood school,” she told parents at her town hall meeting. “What if you had more options at your neighborhood school?”