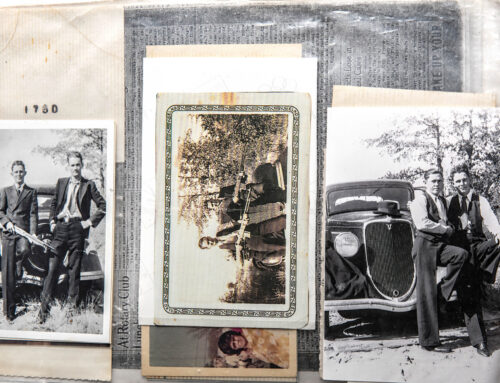

Jack Taylor accompanying a Stamps-Baxter quartet — Charles Collier, Wilford Roach, Clyde Roach and Bert Carroll — for a live radio broadcast in Dallas, April 1958. Photo courtesy of David Spence.

Few people today know that Oak Cliff was once home to the leading publisher of an American roots music known as “shape-note southern gospel.” In its six decades at 209 S. Tyler St., the Stamps-Baxter Music and Publishing Co. printed and sold 20 million songbooks featuring 15,000 original songs.

When Jack Taylor died at his Oak Cliff home on Sept. 15, three days shy of his 94th birthday, he took with him memories of the company’s final 30 years, including locking the door as managing editor for the last time in 1987.

But before Jack was a music executive, he was a performer — the “greatest gospel pianist” that Bill Gaither said he ever heard.

In his hometown of Rockingham, North Carolina, Jack was first trained in classical piano but later was infected by southern gospel.

Pentecostals had invented southern gospel in the late 1800s to get the congregation singing, not just listening to the choir. Problem was, many in the pews couldn’t read the newspaper, much less sheet music. So early publishers adopted the “technology” of shape notes: a simplified annotation that tells the singer which note to hit by its printed shape — square, rectangle, triangle, etc. Shape notes suited the traveling quartets that promoted southern gospel, as they often had to perform songs fresh off the press at revivals and on radio shows with little or no rehearsal.

By his late teens, playing on the road and radio with the Blue Ridge Quartet out of Raleigh, North Carolina, Jack had mastered the southern-gospel style — dramatic arpeggios to introduce a song, ragtime flourishes to let the quartet catch their breath, and pounding the keyboard to be heard under a tent. At one such gig, Jack’s playing launched a startled covey of birds from their nest in the upright.

In 1928, the year Jack was born, Stamps-Baxter moved from East Texas to Oak Cliff, and immediately came to dominate the industry with creative promotions such as children’s music schools, all-night “singings” that filled stadiums, broadcasting nationally from Mexican radio stations to dodge the FCC, and adding “Stamps” to the names of quartets already successful in local markets.

In 1949, Frank Stamps recruited 21-year-old Jack to Dallas to play with his Stamps All-Star Quartet. Most of the company’s 50-plus employees had dual roles — singing or playing gospel music while also setting type or keeping the books. Jack got off the road to marry Betty, an organist and high-school French teacher, and raise their daughter Cindy. A gifted arranger, Jack’s job was to cajole a stable of composers across the South to produce songs at a furious pace, which he would then polish for publication.

On the same instrument he used to work out harmonies during business hours, Jack taught piano privately to young students. To have been trained by Jack Taylor is still a distinction among gospel and country keyboardists.

Jack would outlive brothers Frank and Virgil Stamps as well as “Pap” Baxter and his wife “Ma.” He remained friendly with both sides when a feud split the company and former co-workers were forbidden to meet for coffee. Not until the parties were long dead would he discuss with historians and filmmakers the excesses and frailties to be found in what was really, according to Jack, an entertainment business.

As an elder statesman, Jack loved to gather around a piano to sing shape notes with gospel traditionalists, but he took pride in others like Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash and Willie Nelson, who launched popular-music careers from their early training in church music.

With reason, Oak Cliff boasts of the roster of artists, actors, writers, singers and musicians who were born or found their nest here. By the measure of Psalm 96 — “Sing to the Lord a new song” — it’s hard to match the impact of Jack Taylor.