The Longhorn Ballroom has been a lot of things to a lot of people.

It has been a venue for Black artists to perform during the Jim Crow era. It has been host to counterculture movements before they found their footing. It has been a country bar, and a gathering place for members of the international community. It has been debated in city council meetings and is even tangentially connected to the JFK assassination.

The reopening of the Longhorn Ballroom in March was hailed a victory by music lovers and preservationists alike. The first wave of shows put on at the refurbished venue stuck true to its country roots, but as more shows have been added to the calendar the genre-quirkiness the Longhorn is known for has creeped in.

It might be said that the Longhorn Ballroom was, and is a lot of things because Dallas was, and is a lot of things. One is a mirror held up to the other.

These are the tales from the Longhorn Ballroom.

A PLACE FOR CONNECTION

If you have a question about the Dallas music scene, Jeff Liles probably has the answer and a story or two to go along with it.

Talent buyer for the ballroom in 1986 and 1987, Liles spent his fair share of time up close and personal with the Longhorn Ballroom, and saw the way the venue brought unlikely characters together.

“Part of the initial appeal of punk rock was that it was a confrontational counterculture,” Liles, who now serves as the artistic director of Kesser Presents, says. “Agents booked them at Longhorn because it was a culture clash. A British punk band playing a country western bar was news.”

As a talent buyer, Liles booked the Butthole Surfers who opened for the Flaming Lips. Midway through the show, lead singer Gibby Haynes poured lighter fluid into a cymbal before setting it on fire and hitting it, throwing a fireball into the crowd.

Talk about punk.

But the most impactful show Liles recalls attending was that of Fela Kuti, a Nigerian bandleader and legend who is known as the King of Afrobeat. It was a coup for the Longhorn to book Kuti — he didn’t play many shows in America — and when Liles attended the show it opened his eyes to not only the Afrobeat genre, but to Dallas’s vibrant Nigerian community.

“The Fela show made the connection with the American soul genre to the international Afrobeat community that Dallas didn’t know it had until that night,” Liles says. “It was an extraordinary spectacle.”

THE SHOW

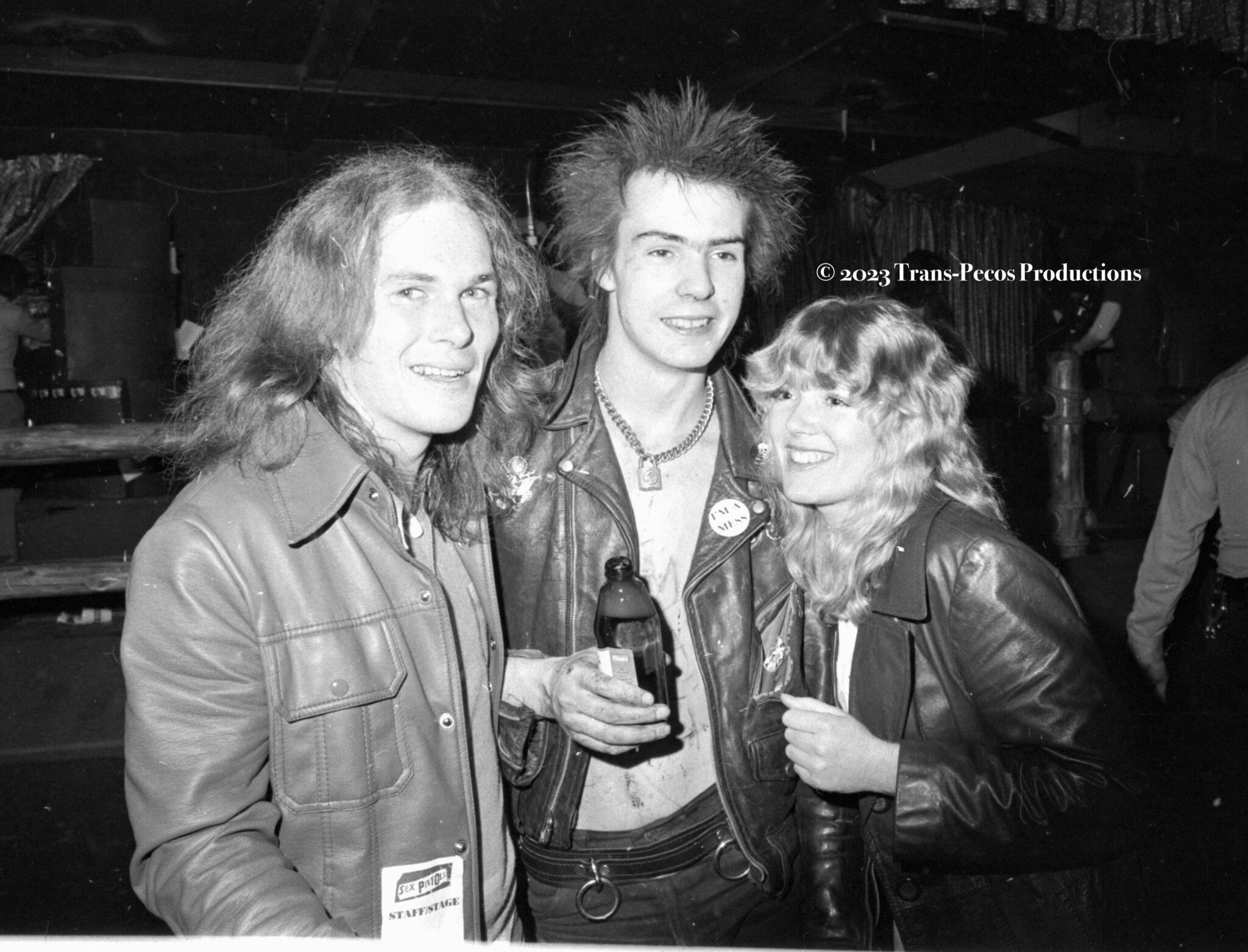

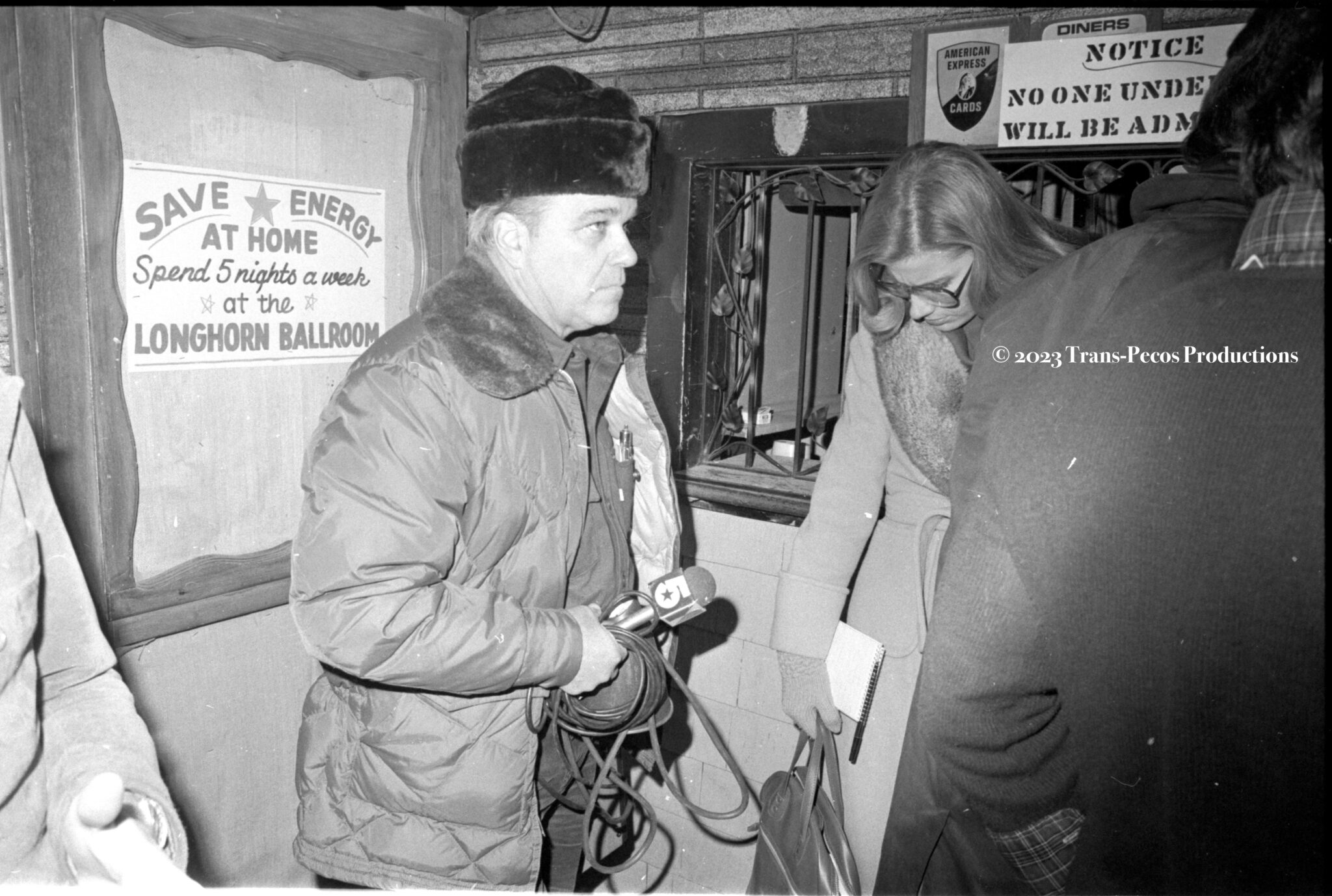

Rolling Stone photographer Annie Leibovitz stood in the corner of the Longhorn Ballroom one January night in 1978 wearing a long brown coat and gloves. The gloves were how Buddy Magazine editor Kirby Warnock knew the “standoffish” woman wasn’t from Texas. (“Here we just put our hands in our pockets,” he says.)

Leibovitz was at the venue to photograph the Sex Pistols during the British punk band’s seven stop tour of America.

Rolling Stone was never able to publish the iconic images of bassist Sid Vicious covered in his own blood, because Leibovitz’s camera was stolen before the end of the show.

Buddy Magazine put out a reward for the return of the camera, but no one ever came forward, Warnock says.

Luckily, his own camera made it through the show unscathed.

“The thing that I remember the most and what I think people have trouble understanding is we thought they were terrible,” Warnock says of the show. “We were there having heard really good musicians in Dallas, and so when they came out they just were not very good. We just thought ‘What is the big deal about these assholes?’”

Warnock said he wrote something to a similar effect in his magazine article about the show, having felt “tricked” by the hype surrounding the band. When Vicious dragged a broken bottle across his chest, drawing blood, Warnock thought “that guy is either really high or really disturbed.”

The opening act of the show, The Nerve Breakers, were a Dallas punk-rock band who Warnock thought out performed the headlining act.

“Of course, (the Sex Pistols) only made one record and only did one tour,” Warnock says. “Looking back on it it was kind of a rare deal and who knew all these years later we’d still be talking about them. But at the time we were just scratching our heads.”

THE LEGACY LIVES ON

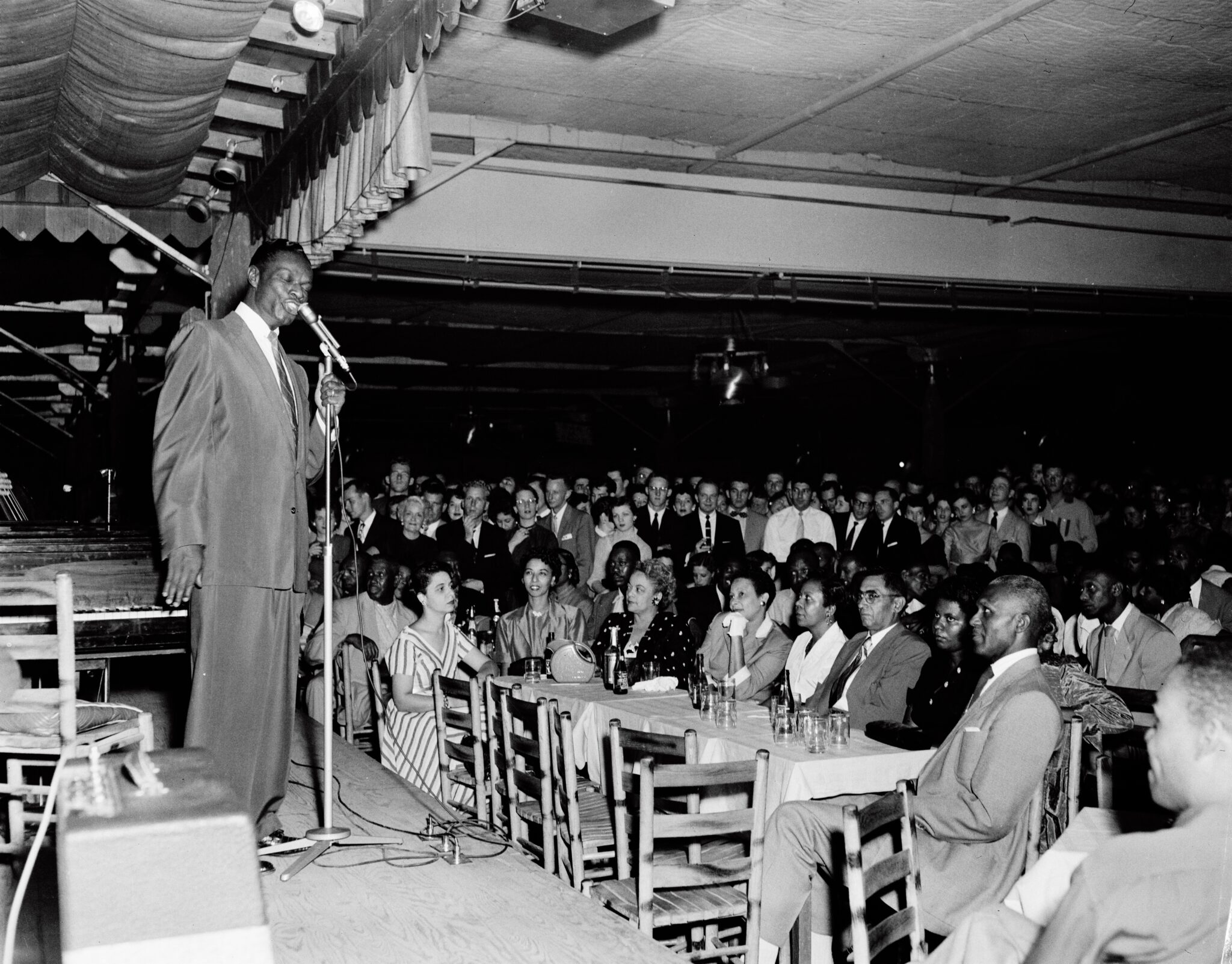

Longhorn Ballroom’s second owner, Jack Ruby, subverted the expectations of the Jim Crow era by booking talent like Ruth Brown and Nat King Cole. The latter was famously photographed during a 1954 show singing to an audience of seated Black patrons, with white viewers standing in the back of the room.

It is a legacy that intrigued Curtis McCray, and part of what brought him to the Longhorn as the senior talent buyer and general manager.

“It hosted major American talent in a time when it was difficult for that talent to tour,” McCray says. “It was a very niche circumstance.”

While McCray says the venue emphasizes its rich history when talking with potential talent, he has found most artists are as intrigued by the ballroom’s history as he was.

“There’s a sense of joining the ranks of the greats,” he says.

“Kind of without fail,” artists have paid respects to the venue’s history since it reopened.

Most acts will perform a song by one of the venue’s past legendary performers (sometimes in unexpected pairings, like the Mountain Goats covering a Sex Pistols song) or acknowledge the venue while speaking to the crowd.

“As a fan and as someone who has worked in the industry, the thing that appeals to me is that it is truly a unique place,” McCray says. “You come away from it like, ‘Oh, I’ve been somewhere.’”

BOBBY’S HOUSE

The Longhorn Ballroom has always been the place Bobby Patterson can be Bobby Patterson.

The Bluesman started performing as a child, and his shows at the Ballroom date back to before the floor was sunk in or the dressing rooms were moved inside. When he was starting out, Patterson played on Monday nights — the day of the week reserved for Black performers.

“Tight friends,” with legends Bobby “Blue” Bland, Z.Z. Hill and Johnnie Taylor, Patterson spent countless nights squeezing into the shoebox sized dressing rooms in the venue parking lot to prepare to take the stage.

“We’d freeze our asses off out there,” Patterson says.

One year, Patterson and Bland headlined a show on Patterson’s birthday. To celebrate, he decided to seek out an unconventional stage entrance.

“I decided I wanted to do something different to come onto the stage because Bobby “Blue” Bland was a very demanding figure,” Patterson says. “So I told this guy that had some horses that I wanted to do something different… and I came on the stage in a chariot. We got it into the back and then put it up on stage. I was sitting in the seat playing the guitar for my entrance.”

The crowd loved it. And, at the end of the show, Patterson was presented with a plaque from Dallas Mayor Ron Kirk, thanking him for his contributions to music and to the city. It remains one of his proudest moments.

On Christmas night, 1999, Patterson recorded a live album at the ballroom. He

hoped to harness the excitement of the holidays into the record, and, like with his chariot entrance, it was unexpected.

“I wanted to record Live From the Longhorn Ballroom because I always loved this place, and I wanted to do it live from here as opposed to any other place,” Patterson says. “And in the audience that night was Johnnie Taylor and Sang’n Clarence.”

Most recently, Patterson performed during the Ballroom’s reopening soft launch.

On one occasion, walking through the refurbished venue, an employee gestured and called it “Bobby’s House.”

“I’ve really been there and done that,” he says.